With an ever-changing technology landscape, the U of S is constantly adapting to integrate technology in the classroom. Getting ahead of the curve is the name of the game.

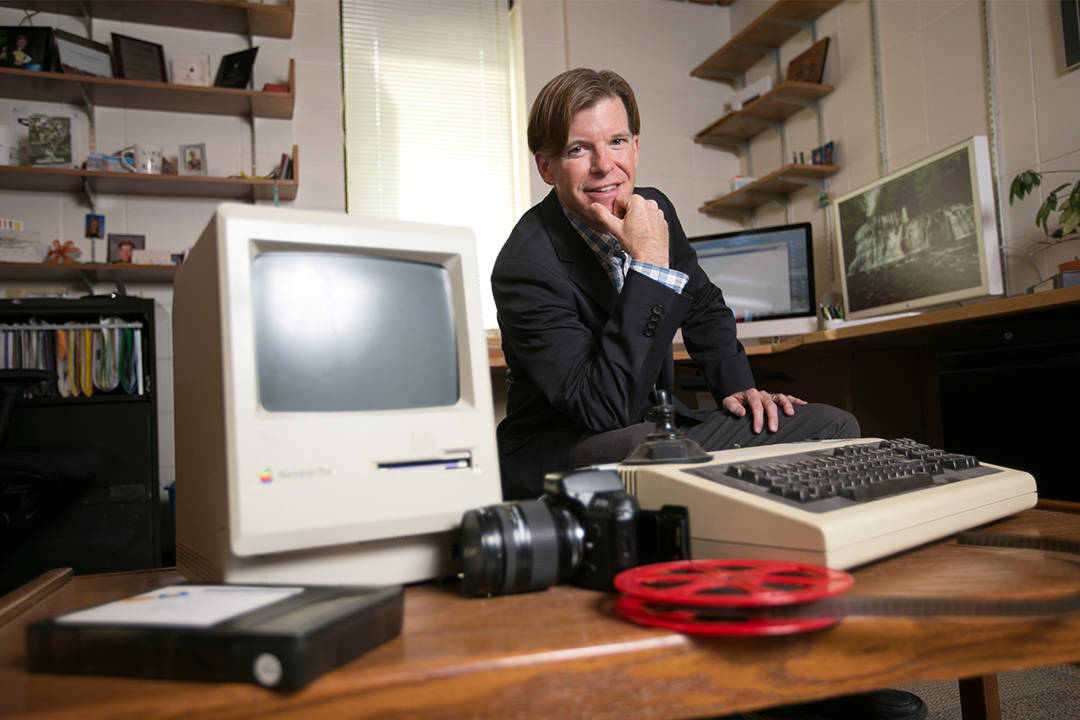

The way University of Saskatchewan students learn has changed dramatically over the last century—a 1916 graduate would be gobstruck by 2016 technology. However, the most remarkable changes have taken place in the last 20 years. Today, a walk around The Bowl shows students constantly plugged into their smart phones, laptops and tablets, whereas 20 years ago you would be lucky to find student with a cellphone. Jay Wilson (BA’89, BEd’95, MEDUC’00), associate professor and head of the university’s Department of Curriculum Studies, has had a front-row seat on how technology has changed, and continues to change, the university’s learning landscape.

“When I started as a student, university profs essentially used the same teaching technology they’d been using for years—film strips, overhead projectors, audio-visuals. The internet signaled a major shift, and everything I do today has grown out of that shift,” Wilson said.

Making distance disappear

In 1995, Wilson had just completed a bachelor’s degree in education when the university recruited him to help figure out how the internet would impact teaching. At first, Wilson was alone in an office with a dial-up internet connection.

“Within a year, we had Mosaic, the first-ever graphical interface, and then came the mouse and then Netscape and then tiny eyeball cameras,” Wilson said. “It was all cutting-edge technology; some worked great, some never worked at all.”

Wilson and a growing team explored ways the university could use the internet, particularly to enhance distance education. “Pre-internet, students enrolled in distance courses received course materials in a shrink-wrapped package in the mail. Students worked through the materials on their own, mailed in their assignments and waited for their marks to be mailed back.”

The internet promised to change all that, but it took another 10 years and the introduction of web 2.0 to move beyond the internet as a portal to information and into the internet as a space driven by user-generated content, interactivity and collaboration.

“Today, distance education students at the university are ‘there’ during the class,” Wilson said. “You can ask questions, post comments and interact with other students. You can use Skype and other interactive software to collaborate. Feedback is easier and more immediate. It all makes the learning experience deeper and more formative.”

Developing digital literacy

Nancy Turner, director of the university’s Gwenna Moss Centre for Teaching Effectiveness, sees the internet as a game-changer for all universities. “Historically, universities were seen as creators and keepers of information and knowledge. The internet democratized that, first by making information more accessible and then, with web 2.0, by enabling individuals to create and disseminate their own content.

“I think universities have responded by shifting focus,”Turner said. “Universities are not only creating and disseminating information, they are also helping students become knowledgeable creators of content and critical consumers of content.”

It’s a well-accepted truism that, whatever your course of study, university teaches you how to think critically. Turner believes it’s even more important to help students learn to filter what they see and hear in the digital world. “Developing digital literacy as part of information literacy is a huge component of learning today at the University of Saskatchewan, and a big change from how students were learning 20 years ago.”

With everyone becoming a content creator, how do universities stay relevant? Turner has no qualms about the future. “I don’t think online learning will replace face-to-face on campus learning,” Turner said. “But I do think it will continue to create opportunities for students to learn online, wherever they live. And even in a traditional campus classroom, technology can help students connect to a community of peers.”

Wilson is equally optimistic. He moved from tech support to university faculty in 2008, has been an Apple Distinguished Educator since 2011, was a recipient of the Master Teacher Award in 2015 and remains keenly interested in technology in the classroom. “For all the success we’ve had using technology to engage students, I think we still need the classroom infrastructure,” he said. “I think creativity is at the heart of the future of education, and technology is a tool that allows people to be creative—intellectually, artistically and academically.”

Preparing for careers that don’t exist... yet

Another unique challenge that ever-changing technology brings is how to prepare students for careers that don’t even exist, at least, not yet. Jason Collins (BSc’94, MSc’96) is a case in point. Growing up in the 1980s, he was fascinated with computers. But when it came time for university, he enrolled in electrical engineering because he didn’t know he could make computers his career. “I switched to computer science after my first year, and only because I had an excellent professor who made me realize it was a career option,” said Collins.

Even then, Collins expected to spend his career in academia, enmeshed in computer languages and algorithms. “It wasn’t until I got a job as a software engineer that I really understood you could build software for commercial purposes.”

Collins went on to become chief technology officer (CTO) at Point2 Technologies, a Saskatoon-based start-up known for real estate industry software solutions. In 2008, he started Vendasta Technologies with several colleagues, again serving as CTO—a role that only gained traction in the last decade along with the rise of computer-based technologies.

In 2015, Collins left Vendasta to join the Google Cloud Platform as a technical solutions consultant at the Google campus in California. “The career I have now with Google was the stuff of science fiction books and movies when I was growing up,” he said. “It’s pretty awesome to see it really happening.”

Where will it all lead?

In 2012, the University of Saskatchewan College of Nursing launched its remote presence (RP) technology to give nursing students in remote locations access to faculty and mentors based in Regina, Saskatoon and Prince Albert. Today, the RP7i mobile robot is an accepted part of nursing classrooms in Air Ronge, Île-à- la-Crosse and Yorkton. It has an articulated flat-screen monitor for visual display, dual camera configuration and full on-board audio that, when used in conjunction with mobile devices and video or web conferencing tools, allow nursing instructors in one location to effectively teach and assess clinical competencies with students in another location.

The RP7i is just one of many tools in the university’s digital resource cupboard. Instructional technologies run the gamut from Blackboard course tools, lecture capture, podcasting, media streaming, remote response clickers, wikis and more.

Even the university’s libraries are evolving, moving away from static stacks to interactive learning commons. Wilson uses an analogy to illustrate the changes: “University libraries are not grocery stores full of books; they’re kitchens—places people gather to create and share ideas. They are evolving into ‘maker spaces’ where students can go and build something or collaborate with a team.”

In just two decades, technology has revolutionized how we access, disseminate and inform. The impact on the University of Saskatchewan faculty, staff, students and alumni has been profound. What’s on the horizon?

“There’s a lot of work going on in augmented and virtual reality and gamification which could change teaching considerably in some fields of practice,” Turner said. “Beyond the next few years, however, it’s anyone’s guess as to where technology will go.”

Wilson sums up the future more succinctly, saying, “I see more of the same—change.”

Going, going gone

It’s out with the old and in with the new for some of these obsolete gadgets. Take a look at the new generation of classroom devices.

| Original gadget | Because it's 2016 |

| Pull-down maps | Google Maps |

| Floppy disks and CDs | iCloud |

| VHS tapes | YouTube |

| Chalkboards | Smartboards |

| Overhead projectors | Data projectors |

| Ink wells | Voice recognition software |

Beverly Fast is a Saskatoon-based freelance writer.

This story appeared in the fall issue of Green & White.