Talking tech

If you own a phone, odds are you’ve used the voice-activated digital assistant to answer basic questions, provide directions, tell a joke or even order a pizza.

By Chris MorinThere are a number of tech companies developing these vocal assistants in one form or another, and these types of digital-human interactions are increasingly becoming the norm. But for all the technological advances, the conversation still manages to fall short of those conversations with another human. While many of these services provide helpful advice and nudges in the right direction, the sentences are often choppy and robotic.

Ian Stavness, an associate professor in computer science at the University of Saskatchewan, believes this literal conversation with technology is only going to get more complex. Now, along with a team of collaborators, he is helping to develop the next generation of speech synthesis using simulations of the human voice.

Currently, if you hear a computer speaking, for example, Siri on your iPhone, Stavness said the process used is called concatenative speech synthesis. This conversation is constructed using a voice actor recording snippets of speech which are then pieced together to form sentences.

That’s something Stavness is working to improve.

“We use investigate articulatory speech synthesis, which builds these interactions based on how humans actually generate speech,” said Stavness.

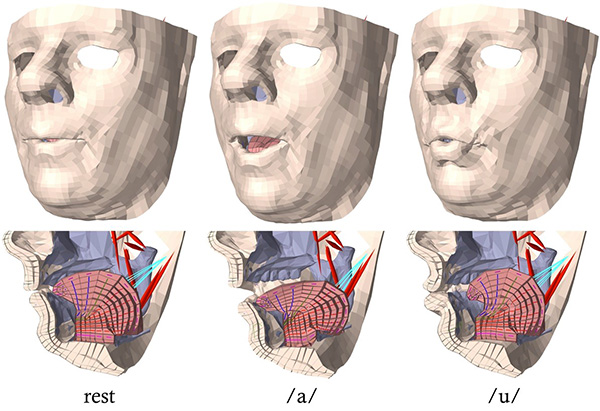

By studying the anatomy that produces speech, such as lungs, tongue, mouth and lips, Stavness and his collaborators are attempting to reproduce the natural way humans talk.

“If we are successful, we will be able to build interactions that are quite expressive. There will be more human-like emotions and tones and characteristics of speech that are more real-to-life,” said Stavness.

“This application also adds a personalized element to synthesized speech. If you have a scan of your own anatomy, for example a medical scan of your neck and head, we can reconstruct a synthesis of your voice that should sound exactly like you.”

While much of the work—a decade-long collaboration with a team of linguists and engineers from the University of British Columbia—is still in the research phase and not yet being used on smartphones, the techniques aren’t just limited to teaching computers.

Building his 3D simulations of human anatomy using medical imaging techniques, Stavness—one of 25 worldwide experts in musculoskeletal modeling and simulation— said these speech applications can also be used in educating humans and even treating serious injuries.

“Since we create the sound by moving a 3D model of the vocal tract, we are able to see this rendering of how the tongue moves in the mouth in order to make sounds,” said Stavness. “So this could help someone with a speech disorder or aid in education for those learning a second language, where there is a certain emphasis on where the tongue is placed in order to create a specific sound.

“It’s often quite difficult to just tell someone how to do this, but computer animation is shown to be successful when it comes to speech rehabilitation.”