Indigenous studies class develops oral history inventory for descendants of Big Bear

University of Saskatchewan (USask) students have been assisting a local group in tracing the history of Big Bear’s descendants through a unique experiential learning project.

By Shannon BoklaschukDuring the last semester, seven students were enrolled in a class taught by Dr. Winona Wheeler (PhD), a professor in the Department of Indigenous Studies in the College of Arts and Science. The course—INDG 351.3: Indigenous Oral Histories Research—explored the forms, qualities, diversities and cultural foundations of Indigenous oral narratives and addressed the practical aspects of gathering, recording, interpreting and utilizing them.

For the community service learning component of the class, students worked on a project with the Big Bear Cultural Society (BBCS), a non-profit group comprised of descendants of the original Big Bear band. On April 4, the students presented their findings to BBCS members.

As part of their coursework, the students searched for oral history transcripts and various archival materials related to Big Bear. Although they didn’t have previous archival research experience, the students were able to develop an oral history inventory sheet for BBCS that outlined more than 100 sources, including online links.

“It feels good doing real-life work that’s going to go to a good cause and also to a community,” said Michelle Zinck, an Indigenous studies student who learned a lot about Big Bear in the process.

“One of the best ways to learn is to be of service to a community in your skills development,” Wheeler told the class.

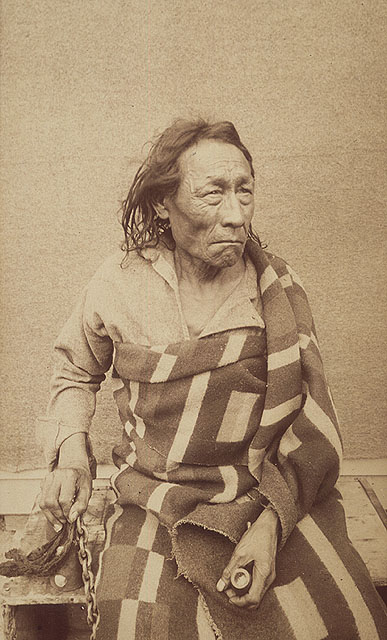

Big Bear (Mistahimaskwa) was a Plains Cree chief who died in 1888 on the Little Pine First Nation in Saskatchewan. Big Bear believed the terms set forth in Treaty 6 were inadequate, and he is best known for his refusal to sign, in 1876, what he saw as an unjust agreement. The treaty was eventually signed in Big Bear’s absence by other chiefs who did not consult with him.

As the online Canadian Encyclopedia notes, Big Bear had wanted to establish a reserve near Fort Pitt in the early 1880s. However, “when he saw the poverty of his friends there, he worked tirelessly—but unsuccessfully—to get further concessions from the federal government. Determined, Big Bear called on Cree chiefs to unite and press the government for one large reserve on the North Saskatchewan River.” The government countered by cutting off rations to the Big Bear band in an attempt to force them to settle. A reserve was never set aside and the Big Bear band dispersed, with descendants scattered throughout Saskatchewan, other parts of Canada and into the U.S., particularly Montana.

Members of Big Bear’s band were involved in the violent conflicts that took place during the 1885 North-West Resistance, and Big Bear was later taken to Regina to stand trial for treason-felony. Although Big Bear was not violent and did not take part in the conflict, he was sentenced to three years in the Stony Mountain Penitentiary.

In recent years, descendants of the original Big Bear band have been attempting to trace their history and to make contact with other living descendants. A gathering of some of the descendants was held in the summer of 2018 on Little Pine First Nation. Another gathering is scheduled to take place in July 2019.

During the 2018 gathering, speeches were made and family stories were shared. The students in Wheeler’s class worked to transcribe and preserve the oral narratives from the event. Because the audio quality of the recordings was poor, the students also worked with the Social Sciences Research Laboratories (SSRL) at USask to learn how to use software to enhance the quality.

At their final class on April 4, the students shared some of the challenges they faced while working on the project, such as transcribing the stories and locating information that was difficult to find. They also relayed the joy they felt when relevant information was uncovered.

BBCS member John Cuthand, who attended the class on April 4 to hear the outcomes of the students’ research, acknowledged the importance of their work.

“The people that know their kinship also know their history,” he said.

Terry Atimoyoo was also in attendance. He said he founded BBCS because he was surprised to learn Big Bear never got any land and he was bothered by that. The original aim of BBCS was to organize a gathering of Big Bear’s descendants, and now the group is looking to do even more, he said.

Atimoyoo described the students’ work as helpful and said it contributes to the goals of BBCS.

“On down the line, what we’re looking at is developing our own archives. Because, right now, all our information is scattered all over the place—in the States, up here,” he said. “Some of the students went to towns or cities to look at the archives. You’d be surprised at the kind of information that you’ll find in the little towns.”

Atimoyoo told the class that having more information about Big Bear’s history and the history of his descendants “is what’s needed by the young people.”

“The oral tradition, it humanizes us,” he said. “It’s important.”

Article was originally published on https://artsandscience.usask.ca/news/