Providing a path to the justice system

When Const. John Langan tells young people they can turn their lives around after a brush with the law, he speaks from experience.

By Chris Putnam“I got in trouble too when I was 14 years old,” said the officer with the Saskatoon Police Service. “I really didn’t think I would be a candidate to be a police officer, but it just goes to show that it’s not over.”

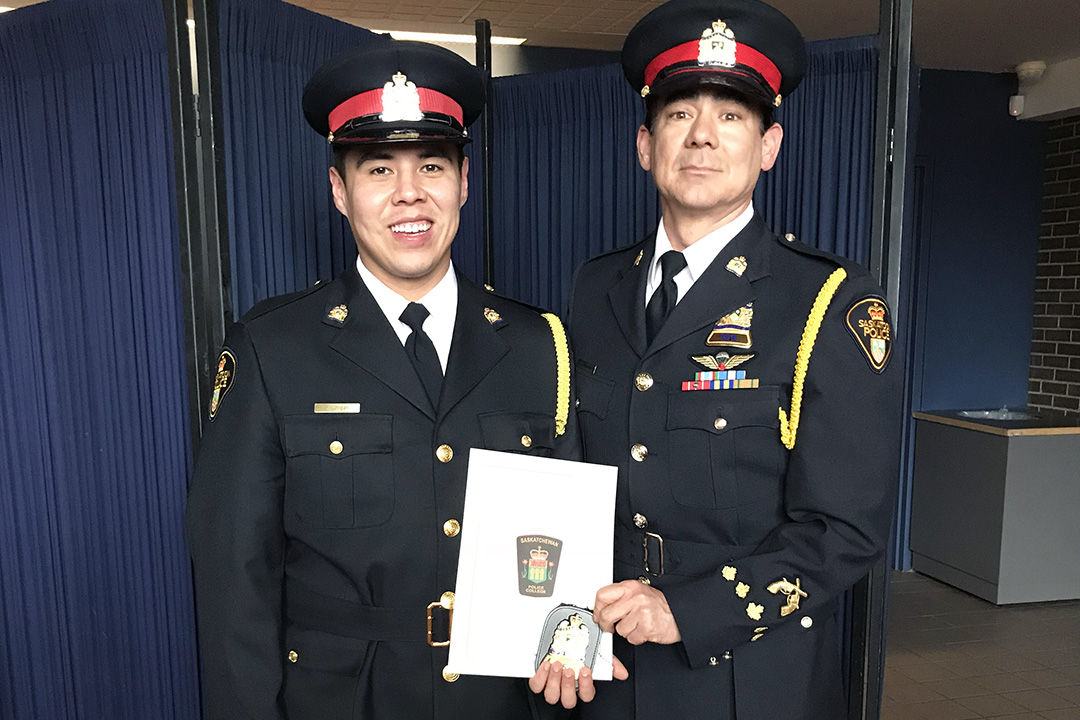

Langan, a member of the Keeseekoose First Nation, built a new life as a Canadian Armed Forces reservist and a University of Saskatchewan student. He joined the police force in 2017 after completing his Bachelor of Arts in sociology in 2013, with a special concentration called Indigenous Justice and Criminology (IJC).

Previously called Aboriginal Justice and Criminology, the IJC program launched nearly 30 years ago in the sociology department of the College of Arts and Science. Today, its graduates are found working in justice-related careers across Canada.

“It’s quite exciting, actually. They’re change-makers in their own communities, change-makers in Saskatchewan, with such a passion for issues of Indigenous justice and social justice,” said Dr. Carolyn Brooks (PhD), head of the Department of Sociology.

The program was developed in 1991 by sociology professor Dr. Les Samuelson (PhD) in response to widespread calls for greater representation of Indigenous people in justice agencies.

“Even today, there is a shortage of Indigenous employees in the criminal justice system, yet they are overrepresented there in custody,” said Dr. John Hansen (PhD), supervisor of the IJC program and a sociology department faculty member.

“It’s important to have a program to address this issue and make a society that is more inclusive of Indigenous peoples, because they have been socially excluded for so long in those institutions.”

More than 100 students have completed IJC, which teaches concepts in justice and criminology while exploring the impact of discrimination on the lives of Indigenous people. The program remains unique in North America for its exclusive focus on Indigenous students and its emphasis on experiential learning.

Students must complete two 12-week practicum courses at workplaces such as penal institutions, community programs and advocacy groups. Langan spent one of his practicums at the Saskatoon Indian and Métis Friendship Centre working with young offenders as they completed community service projects.

Langan said his role as a police officer has benefited from his experiences working in the community with young people.

“That’s what made it a good practicum—really engaging with the youth,” he said.

Larissa Mercredi, a 2015 sociology and IJC graduate, sought out the program because she was interested in justice issues and wanted practical experience. She spent her first practicum with the Saskatoon Tribal Council (STC) justice programs, providing support services to at-risk youths.

“That was my first hands-on experience really being in the justice field, and a lot of it revolved around restorative justice,” said Mercredi.

Like many IJC alumni, Mercredi’s practicum turned into a job after graduation. She is now a justice worker with STC.

Mercredi said that classes through the sociology program also changed her perspective on topics such as crime, trauma and the impacts of colonization, helping her to start her “own healing journey.”

“Because residential schools affected my community in Fond du Lac. It affected my mother, my grandmother,” she said.

Samuelson, who retired from the university in 2018, said he is grateful to see the high levels of success and perseverance among graduates of the program he founded.

“I’m proud, for sure,” he said. “I was glad to be of help in developing other people’s capacities and knowledge. I learned a lot, too—I think we all learned a lot.”