USask collection: Small books tell big stories

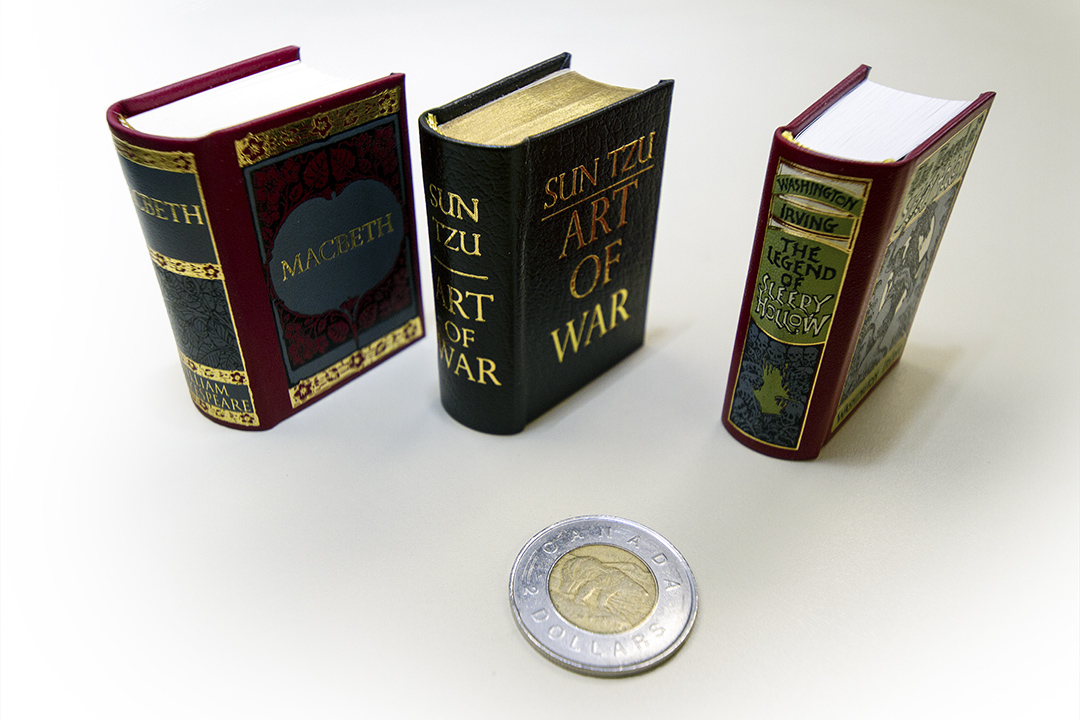

While the phenomenon of the tiny book is largely a product of a bygone era, the University of Saskatchewan (USask) Archives and Special Collections has several of these miniature marvels in its collection, from Shakespeare’s Macbeth to Sun Tzu’s Art of War.

By Chris MorinThe diminutive documents range in size, from a book that would fit snugly in hand to something smaller than a paperclip. Several of the books are so minute that you would need a magnifying glass to actually read them, according to David Bindle, Special Collections librarian at USask.

The collection includes a Bible so small that it comes in a metal case which has a built-in magnifying glass to help the reader see the print. The book, which Bindle said was published in 1901, is almost completely illegible without the glass, but helps tell a story beyond the words in its pages.

“This piece is an example of an early experimentation in photolithographic reduction, a process in which the publishers were able to take a regular-sized printed book and shrink the print down to miniscule proportions through an optical system,” said Bindle.

While many of the tiny tomes are considered something of a novelty now, why did publishers ever bother printing such precious pieces? Portability was often a main consideration, according to Bindle.

“Some of the most interesting small and portable books were handwritten manuscripts from medieval Western Europe,” said Bindle. “They were often commissioned by wealthy patrons who wanted to have a daily devotional book to carry with them at all times. These were often referred to as a book of hours.”

These were not nearly as small as the “tiny” books printed from the early 19th century to today, but they were still quite portable and afforded their owner a certain amount of prestige due to their expense and the fact that to use such a book meant that you were both literate and well educated.

These small books were popular with royalty who had the wealth to commission the best craftspeople to incorporate exquisite paintings called “miniatures”, as well ornate border decorations, and beautiful initial letters of red, blue and gold. Bindle said that although these original books of hours were popular in their day, surviving examples are now fairly rare and command extremely high prices if purchased today—especially the more decorative books.

Some of the tiny books—including one emblazoned with the words “Smallest French & English Dictionary”—were created to be a handy reference as well as a conversational novelty, Bindle explained.

“One can imagine a young women traveling by train across Europe, and this being a parting gift from her parents.”

The dictionary was placed in a locket that could be worn around the neck and featured a magnifying glass on the front hinged cover. Besides the novelty, there was a bit of practicality to it as well. Nowadays, most people don’t leave the house without their smartphone, but over a century ago it was astounding to pack a whole dictionary’s worth of information into something so small.

The smallest of the small books in the USask collection contains the Lord’s Prayer written in seven languages. Produced in 1952, the little book was created as a fundraising item for the Gutenberg Museum in Germany, said Bindle.

“It is leather-bound with a gold gilt cross and border, but the incredible thing is the type itself. This is not a photo reduction, but actual typeset from a printing press,” said Bindle. “To hold this tiny book, with such tiny print in your hand, is just mind-boggling.”