acimowin – to tell a story

Resources for educators to help foster learning and reconciliation.

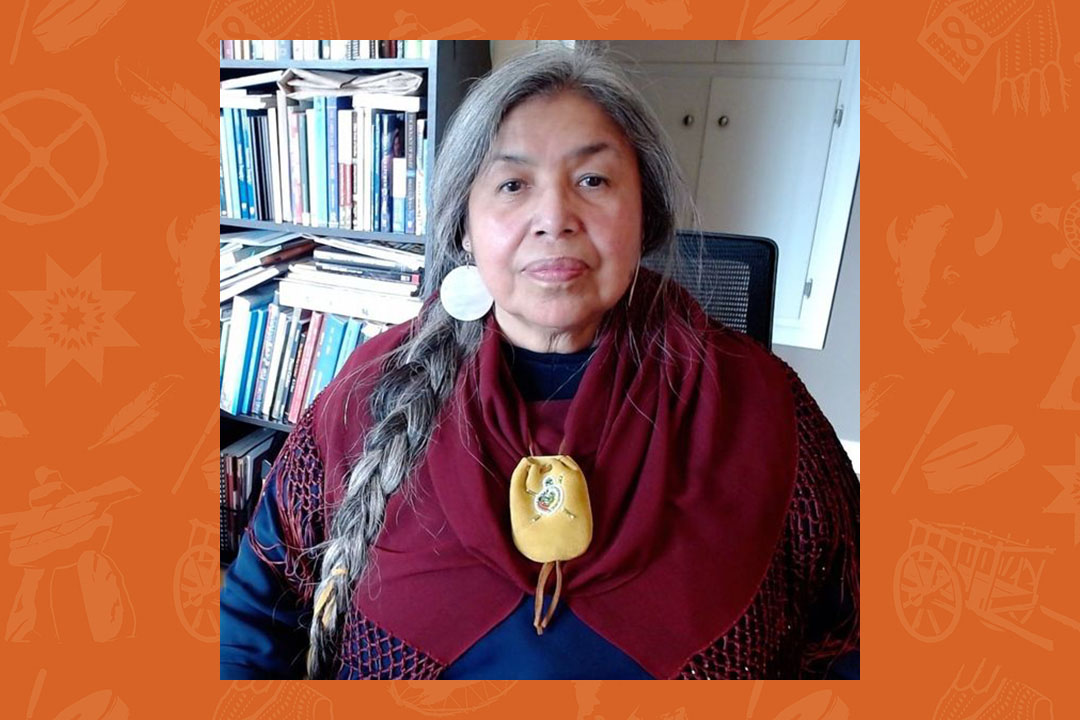

By Meagan Hintherkohkom Linda Young is paskwaw-nehiyaw/Plains Cree from Onion Lake Cree Nation, Treaty 6 Territory. She speaks Plains Cree ‘y’ dialect. She is a Knowledge Keeper, wife, mother, grandmother, great-grandmother, artist, writer, educator, USask alumna (BA’94, BFA’98, MEd’20) and PhD student in the College of Education.

As a young girl, she was taken to attend Saint Anthony’s Roman Catholic Indian Residential School in Onion Lake, Sask. Guardians, whether they were parents, grandparents or great-grandparents, were expected to surrender their children to a residential school as stated in the 1920 amendment to the Indian Act making it mandatory for every Indian child between the ages of seven and sixteen years, to attend Indian residential school.

Four generations in kohkom Linda’s family attended residential school. Her great-grandfather, grandparents, mother and siblings also attended residential school, making her a fourth-generation residential school survivor.

In July 2021, kohkom Linda shared her knowledge, story, resources and advice with K-12 provincial and First Nations school administrators and superintendents, and USask graduate students, faculty and staff at the annual Saskatchewan Principals’ Short Course hosted by the College of Education.

Below are highlights of her presentation as well as links to view videos she created as part of her Master of Education project in curriculum studies – Telling and retelling my residential school survivor story. What was lost, what replaced it, what is needed to heal, reconcile and reclaim Indigenous education for the benefit of students, families and communities.

Available in a one-hour and shorter 16-minute version, kohkom Linda’s video uses a vintage viewmaster projector to click through photos and explore facets of her residential school story and the loss of family, culture and identity. She also explores how to heal, reconcile and ground oneself in language and culture to reclaim what was lost, and the steps all people can take to build relationship and kinship.

During National Truth and Reconciliation Week, we hope that by sharing resources and insights we may begin working together and walking together side by side in a true spirit of reconciliation.

Watch and share kohkom Linda’s video acimowin with students

View acimowin on Vimeo (password: acimowin)

The two videos that I made are meant to be shared and used by educators, whether they are teaching prekindergarten, elementary, high school, adult education or university. It’s for everyone. My hope is for people to use the videos for the purpose of educating themselves and others about the residential school experience.

It’s important for me to be able to share the story in a way that is effective but doesn’t cause a lot of pain. That’s my intent. I don’t share the stories that are heartbreaking, because I’m not there to help close whatever I open in terms of pain.

In the video I talk about the 10 steps and what they represent. Every residential school in Canada has steps leading up to the front door. Some are more or less than 10. Every step taken took me away from my land, my home, my family, my language, my culture and my ceremony. Every step that I took towards those doors took my identity away.

For me the 10 steps are a metaphor to acknowledge the experience that every residential school student had as they entered the schools as wards of the government. Once you entered the doors of the residential school you became a ward of the government and your parents no longer had a say in what became of you.

When I was in residential school, we were told every day that who we were and where we came from was not a good way. And so part of the reclamation process is recognizing that indeed our way of life and our way of doing things is good.

Understand the role residential schools played in separating parents from their children

We hear people ask the question – where were the parents?

I think that is such a good question, because in order for us to really understand where the parents were, we need to know the history of how that came to be.

One of the things is that parents weren’t always welcomed to come in to visit their children because they could interfere with what was happening in the school, which was to deconstruct and reconstruct the Indigenous student to become more western or more ‘white’.

When I read that question I think about how my father, who was Anglican, only came two times to see us. And the reason that he only came two times was because he was not allowed past the foyer of the residential school because he was Anglican. And there was a worry that what we were being taught as Roman Catholics would be influenced by his way of thinking.

We would visit him at the doorway of the school and only for 15 minutes.

We would stand at the door with him and we would put our heads down and he would ask us questions, but we didn’t know what we could say or how we could connect with him. There was this fear of sharing something that we might get into trouble for.

So when people ask the question – where were the parents?

Understand that the parents were there but the access was not.

Open doors as a gatekeeper

Are you a gatekeeper at your school? If you are, you need to figure out how you can form gatekeeping into a more welcoming place for Indigenous families and students.

Opening the doors of the schools and having a welcoming atmosphere is important. School doors must be flung wide open in a spirit of authentic hospitality.

How can we have authentic hospitality? What does that really mean?

For me, authentic hospitality is the way to increase families coming into the schools. If they aren’t coming to school, know the history of why parents were not welcomed or allowed in the residential schools. Once we know that history then we will know how to work with the extended families.

Create a welcoming atmosphere by seeking connection and forming a relationship with Elders, Knowledge Keepers and families in the community.

One of the things that I really loved about the school that I worked in as a Traditional Knowledge Keeper, is that we would have feasts. We would fill the school with families. The parents and the families of Indigenous students felt that they were welcomed. They recognized that it was a place they belonged to.

As my friend and past director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation Ry Moran has said, it’s important to create space for Indigenous people to share what they need to share.

Increase family involvement and teachings within schools

Learn about the traditions that are meaningful to the cultures of students in your classrooms and find a way to bring those into the school.

There is a distinct difference between parent involvement and engagement. And it’s understanding those two. Parent involvement means encouraging parents to volunteer for the school in typical ways like the PTA and field trips. Parent engagement is engaging parents in the co-creation of the curriculum so that they may work with teachers to support the growth of the child in the classroom. For me, it’s being able to understand what that means. How can you bring families into the school in a meaningful way?

Become an advocate for funding and resources to bring in Elders/Knowledge Keepers

Establishing relationships with Elders and advocating for funding to bring in Elders on a regular basis is important so that they can take their place in the schools as teachers. This is an important part of the role administrators play that impacts how students are being supported in schools.

When I worked as a Knowledge Keeper in a public school I purposely used the name kohkom instead of Elder or instead of Knowledge Keeper. Initially, I called myself a Helper but the students called me kohkom, they taught me how important kinship was in my work with them. Over time it became clear that I could only develop that relationship as their school kohkom if I was there on a daily basis.

When I was in residential school, my great-aunt, who was actually my nohkom, worked as a domestic for the sisters, and every once in a while I would see her walking the hallways. I could only wave at her because I wasn’t allowed to talk to her, but I would wave at her and she would wave back. To see my nohkom wave at me at the school helped me stay there for 10 years.

So when I started working in the schools, I wanted to be that kohkom who helped the school become a place where students could come feel safe in. There were these Grade 5 boys, about six of them, and every Tuesday they wanted to have tea with me. Every Tuesday we would gather in my office and we would just talk. When I saw them in high school later they still had that relationship with me. They still called me kohkom.

Additional resources shared by kohkom Linda for educators to explore during the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation:

Art as Atrocity Prevention: The Auschwitz Institute, Artivism, and the 2019 Venice Biennale, Genocide Studies and Prevention: An International Journal, Kaitlin Murphy

How to talk to kids about the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, CBC Parents

National Day for Truth and Reconciliation is 1 step on a long journey, says Murray Sinclair, CBC’s Unreserved