Computer museum serves up USask history, one byte at a time

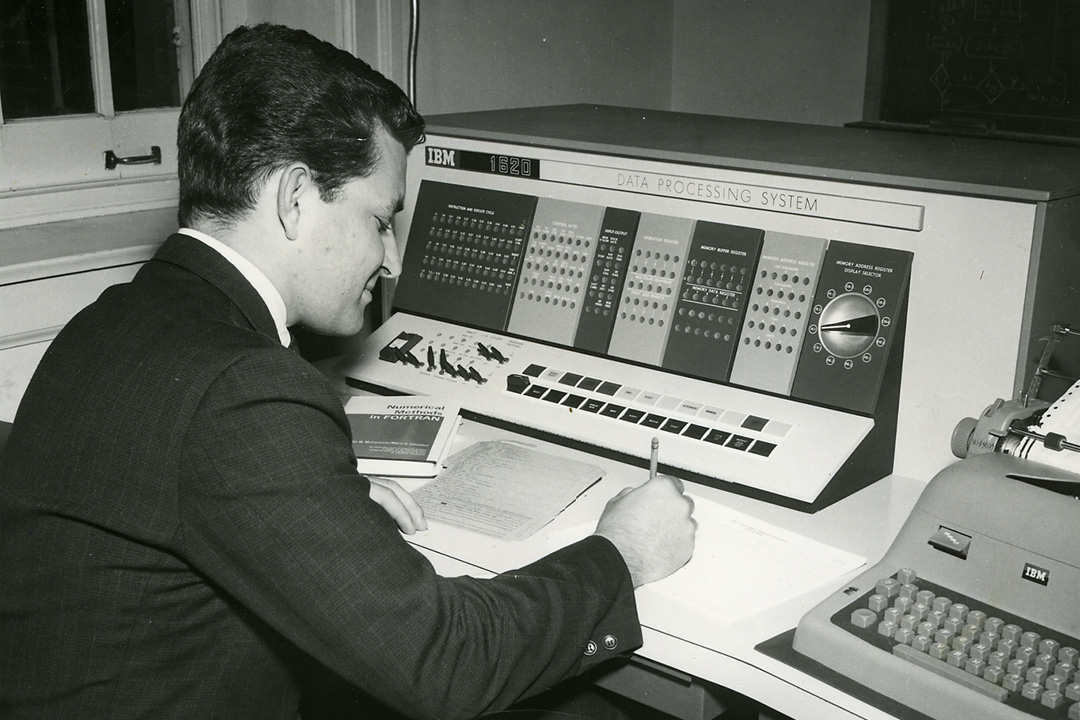

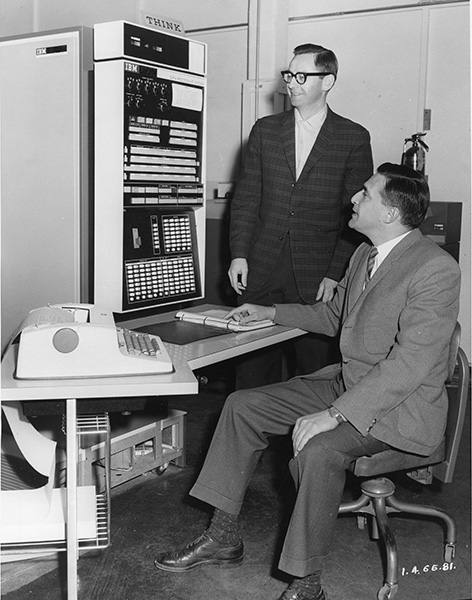

Sixty-five years ago, the University of Saskatchewan (USask) became one of the first universities in the country to enter the computer age.

By James ShewagaPurchased in 1957 for a whopping $30,000 (the equivalent of $280,000 today), the LGP-30 computer that USask first acquired weighed in at 800 pounds and was too large to fit into the elevator in the Arts Building – and had far less computing power than the handheld smart phone that you carry in your pocket today.

That remarkable and relentless advancement of technology over a relatively short period of time is a snapshot of USask history which employees and computer tech aficionados want to preserve, protect and promote.

“Technology changes so rapidly that people lose all sense of appreciation for how the tools that we have today got to be as sophisticated as they are,” said Rob Grosse, a senior USask information technology (IT) support specialist and the first chair of the USask Computer Museum from 2002 to 2012. “To me, the museum is about fostering the appreciation for the technological steps that happened in the past, because without those steps, we would not have the modern tools that we have today.”

The USask Computer Museum is celebrating its 20th anniversary this year, documenting the history of computers at the university dating back more than six decades, including 54 years since the establishment of the Department of Computer Science. Completely volunteer-run and funded, the museum does not have a central location on campus, instead offering tantalizing tastes of timeworn technology, modem memorabilia and primitive processors spread over multiple displays in five university buildings.

“We don’t have a traditional building where you would go to see the museum, but we do have a walking tour where we showcase displays in various locations around campus,” said Greg Oster, the current chair of the museum and the technical team lead in the computer science department. “What it allows us to do is to put artifacts that are related to that discipline – engineering artifacts in engineering, for example – where we can show items related to that discipline.”

“Computing is still a very young discipline. The Department of Computer Science just celebrated its 50th anniversary (in 2018), so it is not like mathematics, which has thousands of years of history. As a result, we are able to capture the beginning of the history of the computer.”

Grosse said what brings the museum to life is not just showcasing computer artifacts dating back decades, but preserving the stories of the people who worked with the technology throughout the history of the university.

“I think we were one of the first universities that recognized the need to archive the technology and the stories while the equipment was still here and while many of the instrumental people who actually used them were still accessible and reachable,” said Grosse. “And I think that’s what makes our museum so great. It fills in a lot of the university’s story, the university’s history, and that’s important. We combine the story with the asset, and when you do that, you have a human story, and an institutional story.”

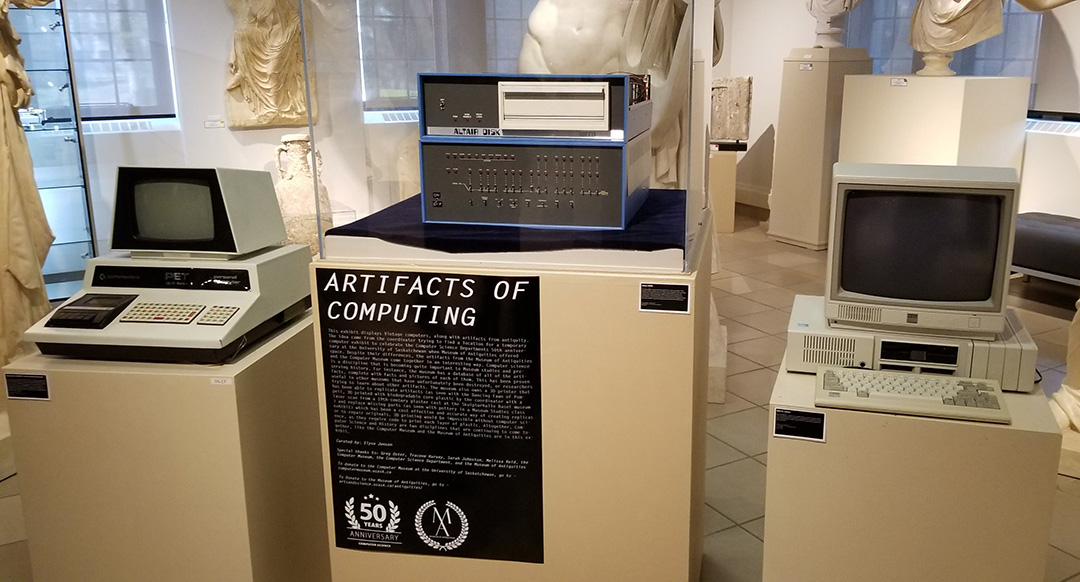

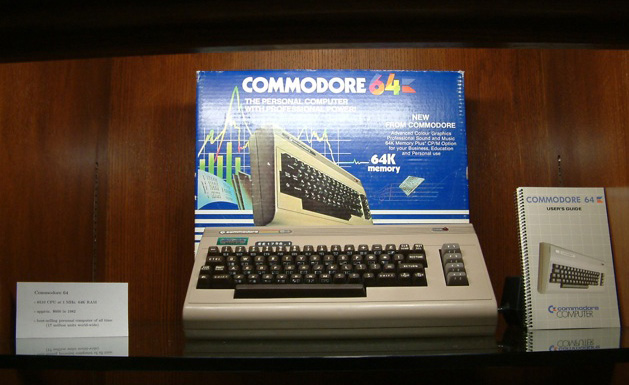

From early Apples and IBMs to Radio Shack and Hewlett Packard, USask’s computer collection contains familiar names and rare models, with some on display across campus and many more secured in storage spaces the museum has acquired. Among the prized possessions for the museum are an Altair 8800, the first personal computer that hit the market back in 1975, a DEC (Digital Equipment Corporation) PDP-8 mini-computer used in the USask physics department back in the 1960s, and one of the original Commodore 64 home computers that first came out 40 years ago.

“(The Commodore 64) was the computer that first got me fascinated with computers,” said Grosse. “But if you are wondering about what in our collection intrigues me the most, I would have to say it’s the Altair. It was basically the first computer kit. It wasn’t actually sold as a whole functioning computer. It was a kit, so it might or might not work when you were done assembling it. It was kind of like a LEGO puzzle … It had no keyboard, no mouse, no monitor, and no printer. But, this was where home computing started in 1975. It was this computer that drove (Microsoft co-founder) Bill Gates to quit college. He saw what was coming and said if we want in on this industry, we have to start now.”

Oster’s favourite in the collection is also the Commodore 64, but points to the Altair as the artifact with the most historical value as a reminder of just how far computer technology has come in the last half century.

“I would call it our crown jewel, or one of our crown jewels. If we were told you can only keep five pieces for the museum, that would be one of them,” said Oster, noting how much an old system like the Altair puts current computer capability into perspective. “The number is 10 billion with a ‘B’. That is how many times more RAM (random-access memory) that a modern system has, versus the Altair 8800 in base configuration.”

But for Oster and Grosse, what really brings the equipment to life are the people associated with the computers. Those stories have been shared in fireside chat events over the years and during the 50th anniversary celebrations of the Department of Computer Science in 2018, when the USask Computer Museum partnered with the Museum of Antiquities to highlight the history of the computer on campus.

“The museum is not just about the artifact, it’s about the story that goes with it,” said Oster. “So, it’s like, ‘This is the Apple computer that was used by the professor who was teaching the astronomy class for 35 years, and this is the computer that he used for the NSERC Award in Chemistry to do research. This is the Commodore 64 that came out of engineering, where they used it in the lab to study bus interfaces and data collection using integrated circuits, or whatever. And it is nice to say that we have an Altair and we have a PDP-8, but what was it used for? Well, it was used for space trajectory calculations and it came from the physics department, and we have that machine. So, it’s that back story that tells the whole story.”