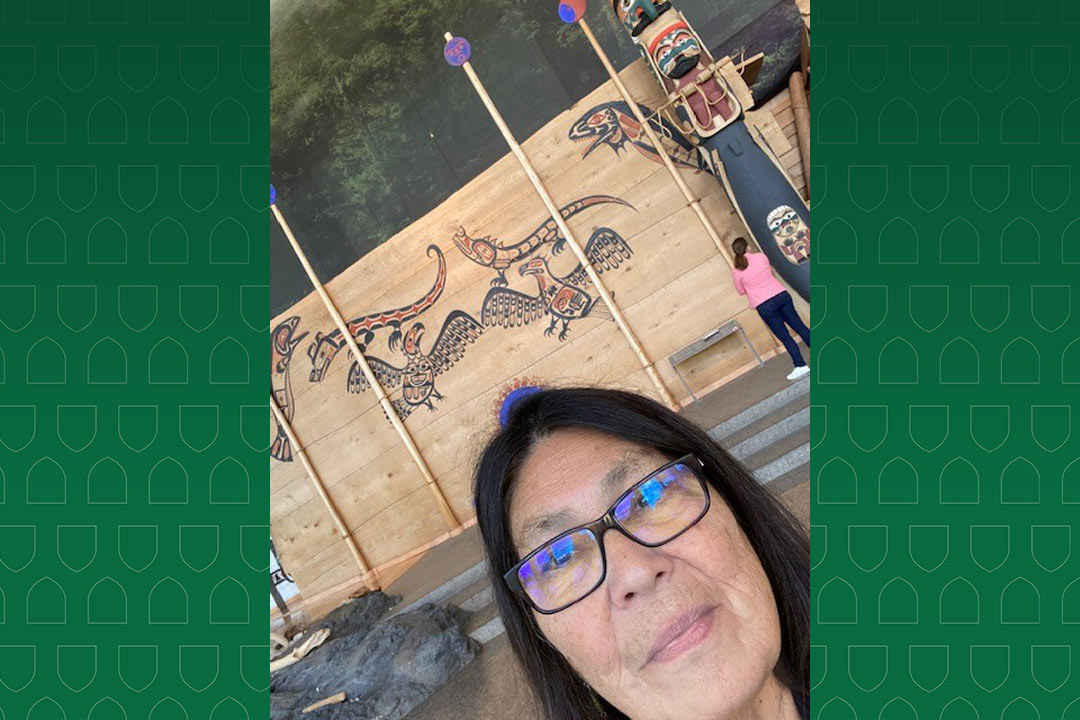

Settee brings a northerner’s perspective to global climate issues

USask Professor Emeritus Dr. Priscilla Settee (PhD) has been invited to speak to Canadian and world leaders on climate issues

By Chris PutnamThe story of climate change’s impact on northern Indigenous communities is being taken to the international stage by a University of Saskatchewan (USask) researcher.

Dr. Priscilla Settee (PhD), USask professor emeritus and interim vice-dean Indigenous of the College of Arts and Science, returned last week from a cross-Canada trip where she spoke about her research to First Nations and federal government leaders. Settee has now been invited to COP27, the 2022 United Nations Climate Change Conference being held in Egypt next month.

At the end of September, Settee addressed the 600 attendees of the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) Second National Climate Gathering in Fredericton, N.B., then travelled to Ottawa, Ont., at the start of October to advise the federal government on Canada’s climate policy.

“I always analyze things through the eyes of a northerner, because that perspective is so critical,” said Settee, a member of Cumberland House Cree Nation in Northern Saskatchewan.

Settee is an expert on Indigenous food systems and food sovereignty. Her 2020 textbook Indigenous Food Systems: Concepts, Cases, and Conversations is the first book of its kind in Canada, and Settee recently examined hardships facing northern trappers through a David Suzuki Fellowship.

“Food is at the centre of everything for all of us, whether you’re Indigenous or not. But from a marginalized community’s perspective, it’s critical to make sure that the natural order of things is preserved—especially where people still live off the land through fishing, hunting, trapping,” said Settee, who retired this summer from her faculty position in the Department of Indigenous Studies before taking on the role of interim vice-dean Indigenous.

Settee spoke to the crowd at the AFN conference about the growing threats to food sources and livelihoods in Indigenous communities caused by climate change and industrial development. As Settee reported through her work with the David Suzuki Foundation, the habitats of animals on which northern residents rely are being destroyed by mining, forestry and the warming climate.

“(My presentation) was very well-received. Over the last 10 years that I’ve been teaching about this, it just seems to turn a light on for people who hear these issues discussed. They can relate to it, whether they’re Indigenous or non-Indigenous,” Settee said.

Settee’s next stop was Ottawa and Gatineau, Que., where she was part of a small group of Indigenous scientists and social scientists invited to a series of meetings with Environment and Climate Change Canada to consult on climate issues. The group’s work will inform the actions Canada will take in response to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Settee spoke in Gatineau about food sovereignty, including her concerns over Canada’s current model of resource development.

“With the amount of wealth being taken out of our North, Indigenous communities should be powerful and wealthy, but they’re not. And why is that? Because that wealth all escapes the North, and very little of it is invested back. That’s a problem,” she said in an interview from Ottawa.

Settee’s work this fall led to an invitation from the United Nations to COP27 in Egypt, where she has been asked to contribute to discussions hosted by the UN’s Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform.

When it comes to both climate change and resource development, the focus should now be on solutions rather than talk, said Settee. She found encouragement from the presence of young people at the AFN conference who spoke about solutions ranging from renewable energy installations to grassroots activism.

“To see these youth in charge and feeling so optimistic was really inspiring,” Settee said.