USask academics channel ‘content creators’ to enhance student learning

Microbiologist, librarians and — YouTubers?

By Jeanette NeufeldThose aren’t words that often go together, but during the COVID-19 pandemic two University of Saskatchewan (USask) faculty members found a way to make the most of a worldwide pivot toward online learning.

Dr. Joe Rubin (DVM, PhD), an associate professor at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine (WCVM), was on a sabbatical leave when the pandemic began in 2020. As most North Americans began “social distancing” and Zoom became a household name, he shifted his focus toward teaching a completely online classroom.

“Vet school is difficult enough when you’re in the classroom and things are going really well. But knowing students would be in front of their computers for six hours a day of class and the rest of the day for study time, I knew it was going to be really, really difficult,” said Rubin.

Adding to the challenge are the high expectations that students have for quality online content. They’re used to seeing a constant stream of well-produced and entertaining videos — thanks to increasingly accessible camera technology and the proliferation of TikTok, Instagram and YouTube videos.

“I think there are a lot of lessons we can learn from the content creators who are interacting with our students’ generation. There’s a reason that they get millions and millions of views,” said Rubin.

Over the first few months of the pandemic, Rubin began rebuilding his veterinary bacteriology and mycology course for an online audience.

Meanwhile, USask associate librarian Carolyn Doi was preparing to teach her upcoming music research methods course fully online for the College of Arts and Science’s Department of Music.

Both academics were going through a similar process of creating videos — and both approached their work with the goals of captivating their audiences and creating content that could live beyond the confines of one course.

“If you’re putting in all that extra time, you might as well share as widely as possible,” said Doi, who created her own YouTube channel before the pandemic. Her channel now includes the videos she prepared for her course, showcasing various techniques for music research.

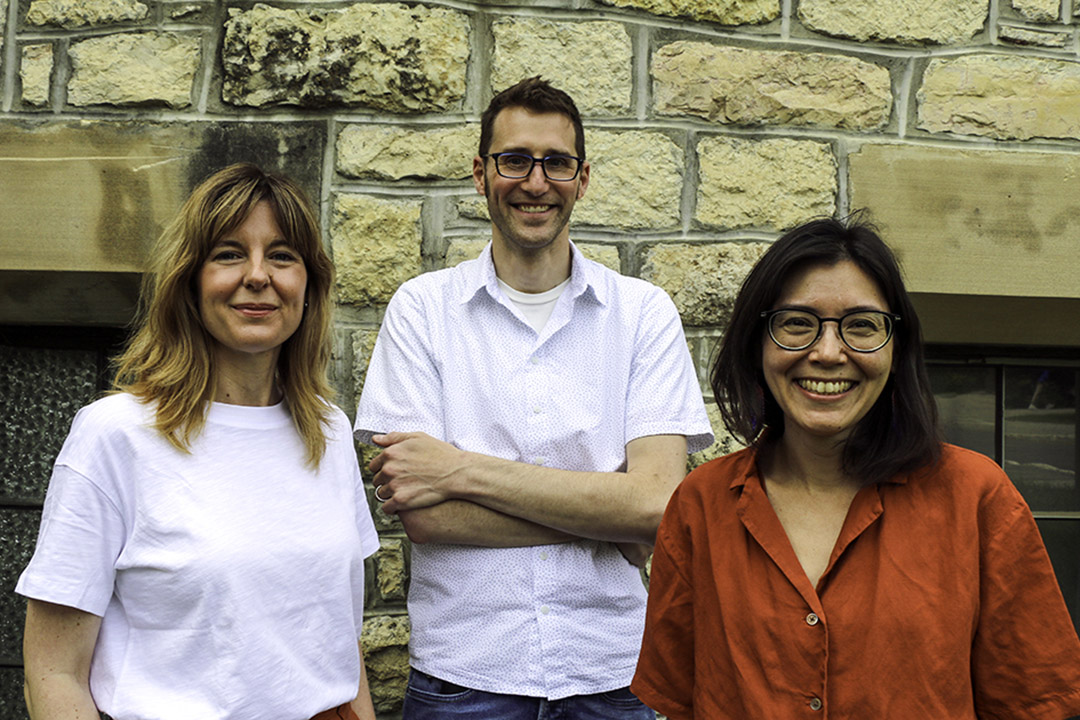

Doi and Rubin had sought help from Shannon Lucky, a mutual friend who is an information technology librarian at USask. Lucky realized that despite the differences in their disciplines, both were approaching their new teaching challenges in very similar ways.

In August 2020, Rubin, Doi and Lucky began meeting as a group to support each other in creating learning materials and to discuss ways of ensuring that their work could provide value to their respective academic communities as open educational resources (OER).

“There’s no reason to duplicate these efforts. Why lock it up in Canvas [USask’s learning management system] when I can make it widely available to anyone?” said Rubin.

“Other than very basic microbiological techniques, it can be really difficult to access resources for people in developing countries. This can serve as essentially a how-to guide for undergraduate or graduate students anywhere in the world.”

His YouTube channel, The Rubin Lab, has racked up more than 20,000 views. Interest spikes around exam seasons or when another instructor includes the videos in a course.

In addition to his videography, Rubin curates an open-access collection of microbiology slides and other images on Flickr. These images receive thousands of views and have become a valuable resource for Rubin’s scientific community.

Doi followed a similar path, spending hours on video creation and editing. She also created podcasts and written materials. Both spent a lot of time creating their videos and wanted to increase the lifespan of their work.

“I think because we live in this busy culture and we’re always short on time with our own work and teaching, it’s easy to look past sharing things openly as an option,” said Doi. “It just seems like one more step, but I think that if we think about the broader community of learners and teachers out there, it’s a way of contributing to that community that can go in directions you may not even anticipate. That can be really rewarding and useful.”

No matter what the discipline, “compiling and creating OER can produce learning materials that are better suited to instructors’ courses and are as good as, or better than, mass market textbooks,” said Rubin.

They also saw a gap in the literature around how to create these resources, so they teamed up with Lucky to author a paper that documents their experiences.

“Often creating OER is something that instructors would like to do, but it’s kind of a ‘nice to do,’ not a ‘have to do.’ We’re in this context with COVID where we had to move all of these things online and other instructors had to start generating all of this digital teaching material, and we thought it would be interesting to see this as an opportunity rather than a burden,” said Lucky.

Published in an open access journal — part of their goal to ensure their work provides value to the greatest number of people possible — the paper serves as a case study of their online classroom experiences and a how-to manual for other academics who see opportunity in following a creative digital strategy.

“Veterinary medicine and microbiology and music librarianship are maybe as different subject areas as you can get, but the approach that we wrote about can really work for people teaching in any subject area,” said Lucky.