USask graduate student aims to improve space travel through plasma research

As a young boy growing up in Iran, Arash Tavassoli was fascinated by outer space and read many books on the subject.

By Shannon BoklaschukNow, as a graduate student at the University of Saskatchewan (USask), Tavassoli is exploring some of his childhood interests through cutting-edge research on plasma physics and its applications for future space travel.

“Essentially what we are doing is contributing to my childhood fantasies,” he said with a laugh.

Tavassoli is pursuing a PhD in physics under the co-supervision of two professors in USask’s College of Arts and Science: Dr. Andrei Smolyakov (PhD), from the Department of Physics and Engineering Physics and Dr. Raymond Spiteri (PhD), from the Department of Computer Science. The USask researchers also collaborate on plasma propulsion with scientists Dr. Yevgeny Raitses (PhD), Dr. Igor Kaganovich (PhD) and USask graduate Dr. Ivan Romadanov (PhD), from the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory at Princeton University in New Jersey.

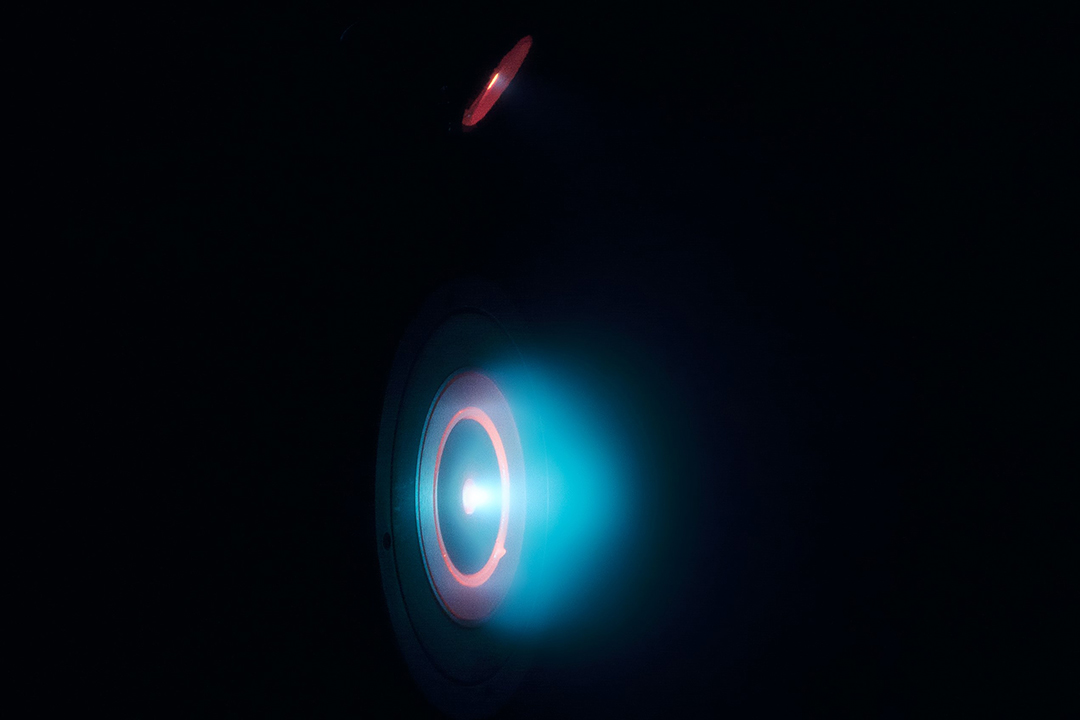

An interdisciplinary scholar who earned degrees in electrical engineering and physics in his home country, Tavassoli is aiming to combine physics and computer science to help designers of plasma thruster engines enhance the capability and efficiency of the machines. Improving the plasma thrusters could ultimately improve the way spacecraft and satellites travel through space, with the propellants accelerated by the electric field rather than through traditional, and more simplistic, heat-producing chemical reactions.

“What happens in that plasma is not well understood,” said Tavassoli. “We are using computer simulations to understand what’s happening inside those thrusters, and that can help us a lot if we want to increase the efficiency.”

Plasma, which is formed by co-existing negative and positive charges, is the most abundant material in the visible universe; the sun is a giant plasma ball, for example, and other stars also mainly consist of plasma. On Earth, plasmas are created in labs for use in a wide range of devices, such as light sources and sensors, and are integral in computer chip manufacturing. Plasmas have also been successfully used for satellite propulsion—in what are known as Hall-effect electrical thrusters and ion engines—and it is this type of spacecraft propulsion in which Tavassoli is most interested.

“In comparison with traditional chemical fuels, using plasma can substantially reduce the mass of the required fuel and therefore increase the useful load,” he said.

To use plasma effectively in satellite engines, Tavassoli said it is important to understand the behaviour that plasmas can exhibit in such conditions. Though scientists understand the fundamental equations of plasma physics, these equations are extremely hard to solve on paper and therefore scientists mainly use computers to solve them, said Tavassoli.

“Through plasma simulations, we can find ways to manipulate its behaviours,” he said. “To this end, various computational methods can be used, each of which has their pros and cons. A method developed in the 1960s is called particle-in-cell. This method is relatively cheap for using in a computer, but the accuracy of the solutions it provides has been criticized and debated.”

As a result, Tavassoli and his co-researchers are working together to develop a computer code that uses a more accurate approach than particle-in-cell for solving the plasma equations: the continuum Vlasov integration method. In a recent publication in the journal Physics of Plasmas, on which Tavassoli was the lead author, the researchers demonstrated how using the Vlasov method can improve simulation results when compared to the particle-in-cell method. The space propulsion research is funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Compute Canada, and the Air Force Office of Scientific Research in the United States.

“Using the Vlasov method, we have also investigated various phenomena that have broad implications in the design and control of plasma thruster engines. An example of these phenomena is particular kind of waves that propagate in an unexpected direction and can lead to the sputtering of the cathode used inside plasma engines,” Tavassoli said.

“We have also investigated a particular phenomenon called the electron-cyclotron drift instability that can affect the efficiency of the Hall-effect thrusters. We believe that these findings can help the designers of the plasma thruster engines to improve the capability and efficiency of these machines in the future.”

During his time at USask, Tavassoli has been the recipient of several awards and honours—including a Teacher Scholar Doctoral Fellowship—and is now teaching an undergraduate physics course. In December 2021, while continuing to work on his PhD, he wrapped up a four-month Mitacs internship with Serious Labs in Edmonton. Mitacs supports collaborations between the academic community and industry partners, and Tavassoli’s internship focused on improving algorithms for object collision detection and resolution for augmented and virtual reality simulations. He sought to refine calculations to better predict how objects will interact with each other if they collide, thereby enhancing virtual reality simulations used to train heavy equipment drivers and, ultimately, improving road safety.

Tavassoli, who came to USask in 2017, is pleased to have the opportunity to teach, learn and conduct research in the College of Arts and Science, where interdisciplinary scholarship is valued and encouraged. He is enjoying using knowledge drawn from both computer science and physics and sees himself as a bridge between the two disciplines.

“We have computer scientists on the one side and we have physicists on the other side, but we need some people to understand both of them and who can work between them,” he said.