St. Denis’s legacy of advocacy and anti-racist scholarship threaded throughout her time at USask

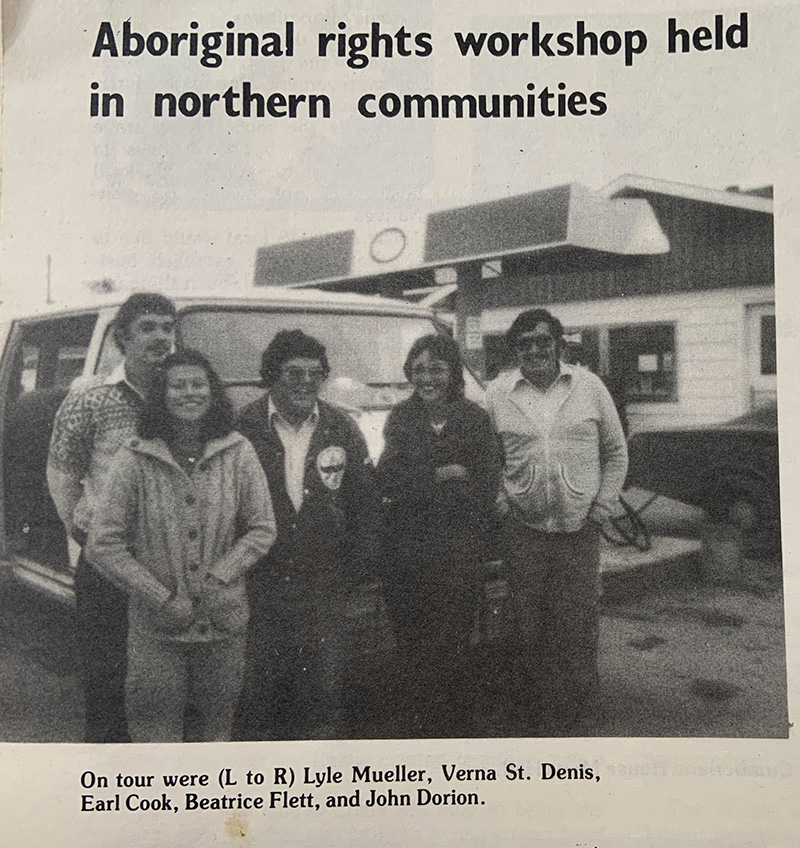

Dr. Verna St. Denis’s (PhD) 45-year journey with the University of Saskatchewan (USask) began over dinner one evening in winter 1978.

By Meagan Hinther“My mom invited me for supper just as I was about to turn 20 years old and said ‘bring your high school transcripts’. She had in mind to introduce me to the idea of going to university,” said St. Denis, now professor emerita in the College of Education’s Department of Educational Foundations at USask.

Unbeknownst to St. Denis, the supper would include a special visitor invited by her mother Helen: the late Reverend Danny Umpherville, a retired teacher and Anglican minister from Muskoday First Nation who at the time was a staff member of the newly established Indian Teacher Education Program (ITEP) at USask.

“Danny Umpherville was a legend in many parts of the Indigenous community,” shared St. Denis. “He looked at my transcripts and suggested that I find him the next day in his college office.”

St. Denis recounts how she came to campus and walked into the ITEP offices and student lounge on the third floor of the Education Building.

“There were students making tea and cutting up bannock and they had their margarine and jam, and I was taken aback seeing ‘our’ food in such a place,” St. Denis said.

After filling out an application and taking part in a brief interview, St. Denis was offered a spot in the program by Dr. Ken Whyte, a Métis scholar and director of ITEP. She would begin university a couple of months later in May 1978.

St. Denis, now a member of Beardy’s and Okemasis Cree Nation, grew up as a non-status Indian and Métis in the Parkland region of Saskatchewan. As such, she was ineligible for tuition funding as an ITEP student. Dr. Whyte shared with her that Métis and non-status students were holding a meeting in a few weeks with the Ministry of Education to lobby for funding and that St. Denis may want to attend.

“As I walked into the full room, I saw Métis students running the meeting. I was blown away watching government people not being able to speak honestly or directly to these students, not being able to respond,” shared St. Denis. “It was so empowering to see. I had never seen Indigenous people stand up to people in positions of authority like that. It was powerful.”

Moments like these would shape St. Denis’s early path at USask. ITEP instructors saw her potential and within her first two months of taking courses at university, she was invited to take on a role as a student researcher for the Association of Métis and Non-Status Indians of Saskatchewan.

“In six weeks, I went from being the kitchen help at one of Saskatoon’s finest restaurants to working in government documents and doing research on Métis land claims,” said St. Denis.

St. Denis describes the feeling herself and other ITEP students would have of feeling disconnected and critical of content presented in some of the required classes for education students.

“I was doing historical research in government documents, and then we had to take this colonial and racist history from the history department, and it was offensive. We started saying ‘we need our own Native Studies department,’ and away we went – ITEP students with me tagging along.”

As a member of an active group of Indigenous students, she would become increasingly involved in advocacy. The group would eventually incorporate as Saskatoon Métis Local #126.

“I was part of it, and I wasn’t outspoken, but I knew that educational and social change were so needed, so I showed up where people needed to show up. And I was part of a group of people trying to make change at the university and in the broader community,” said St. Denis.

It was as a student in ITEP that St. Denis was first introduced to words like decolonization and colonialism through the works of Howard Adams, Harold Cardinal, and others. In the Indigenous education community, she was mentored by faculty members like Rita Bouvier, Dr. Priscilla Settee (PhD) and Dr. Sherry Farrell-Racette (PhD). An undergraduate course with an anti-colonial perspective, including a focus on Apartheid in South Africa, was particularly life-changing for St. Denis. It was called Schools and Society and taught by now Professor Emeritus Robert Regnier.

“Any kind of content that dealt with justice and injustice attracted me,” said St. Denis. “I grew up in between different communities: my dad — Métis — and my mom — First Nations — and a pioneer, settler rural town where I attended school. We grew up struggling as a family. The summer I started in ITEP four of my five brothers were in prison. Crimes of poverty. Young Indigenous men.”

St. Denis speaks of the motivating factor this experience was to her learning and pursuit of higher education: to deconstruct the way society saw her brothers versus her experience growing up with them as kind people with promise and potential.

“I wanted to explore why our society would spend that kind of resource. Why resources would go to funding jail instead of funding adequate supports for education, training, and employment,” explained St. Denis.

Following her graduation from ITEP and time spent as an instructor in the newly established Saskatchewan Urban Native Teachers Education Program (SUNTEP) program, St. Denis would continue with a master’s degree in community development at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Upon her return to Saskatoon in 1989 she was hired as a mentor/instructor in ITEP, teaching a suite of undergraduate courses focused on Indian and Northern Education.

“By virtue of being white”: anti-racist learning in teacher education

In 1992, St. Denis was hired as a faculty member in the Department of Educational Foundations at USask.

“In my second year as faculty, I was asked to develop the required mandatory cross-cultural education course for the undergraduate program. That was a huge responsibility, and I didn’t have a PhD, but I had 10 years of teaching at the university,” she said.

The course focused on anti-racist content and helping teacher candidates understand the links between racism today and the history of colonialism in Canada. Anti-racist education addresses how issues of race and social difference are matters of power inequity.

“I think the course was transformative, if I can say that,” said St. Denis. “I believe this college was the first in the country to ever have a required course in anti-racism and teacher education.”

St. Denis would take a three-year educational leave in 1994 to complete her PhD residency requirement at Stanford University on a Fulbright scholarship, before returning to the educational foundations department to continue teaching undergraduate and graduate students while completing her dissertation research.

It was during this time that a former master’s student in the College of Education, Dr. Carol Schick (PhD), would focus her PhD research at the University of Toronto on cross-cultural education courses and the experiences of the first few cohorts of white pre-service teachers that took the course St. Denis had developed. Schick is now professor emerita with the University of Regina.

“Carol wasn’t interested in how such courses were taught, she was interested in the students’ reception of the content,” St. Denis said.

Schick’s 1998 thesis, By Virtue of Being White, Racialized Identity Formation and the Implications for Anti-racist Pedagogy, found processes by which white pre-service teachers who take such courses continue to demonstrate liberal values and innocence from racist acts, while using language which maintains and asserts their racial dominance.

“That kind of teaching, that kind of critical, anti-racist education really challenges a student’s sense of themselves as innocent and good,” explained St. Denis. “It enables white pre-service teachers to rethink who they think they are.”

In the winter of 1998, Schick and St. Denis co-taught two sections of the cross-cultural course together at the College of Education, incorporating elements from Schick’s research into the original content developed by St. Denis. They continued to learn from each other and discussed the strength each brought to the challenge of teaching critical education.

“It was powerful to see the impact it had on students,” said St. Denis. “Some of it was distressing as students can respond very defensively. But it was powerful to see those students who were ready to have their eyes opened to practice and consequences of patriarchy, misogyny, homophobia, classism, racism, and colonialism.”

Drawing on several semesters of teaching together, and based on their experiences, the pair wrote three self-reflective articles which would become part of the first waves of scholarly work in integrated anti-racist education in North America: What Makes Anti-Racism Difficult in Teacher Education; Troubling National Discourses in Anti-Racist Curricular Planning; and Critical Autobiography in Integrative Anti-Racist Pedagogy.

Over time, St. Denis saw changes in undergraduate students taking the course as their understandings of racism, whiteness and privilege were dismantled.

“However, they would behave in class, and sometimes it was very rude and very defensive, there was always someone who would come back in a month or six months, or send me an email and say, ‘I understand now what you were trying to teach us’,” St. Denis said.

“When that happens over a few times, you begin to realize that who our students are in class is not necessarily who they will become. That change is possible, even if it doesn’t happen in the course’s 13 weeks,” she shared.

“A privileged place”

St. Denis has endured multiple losses in her family throughout her time at the university, both when she was a student and during her tenure as a faculty member.

“The tragedy that we hear, it’s not somebody else’s life. It’s my life,” St. Denis said. “Yet, here I am in this privileged place working at the university. I’ve always felt that it was a position of great privilege and great responsibility and I’ve tried to do my best. I’ve tried to encourage people to see us, Indigenous people as people.”

When asked what kept her continuing to do the challenging work of dismantling perceptions that maintain systems of racism while working and teaching in a colonial institution, St. Denis shared that it’s the students.

“It’s the students, and especially the graduate students that I’ve taught and supervised—their enthusiasm and their commitment and their earnestness, their sincerity, and their desire to make a difference,” said St. Denis. “I worked with a lot of students who had experience teaching in K-12 and they saw the problems, and the teachings I offered spoke to that.”

Changing the conversation

The path St. Denis has forged is closely linked to USask’s goals supporting Indigenization and provides a roadmap for the challenging work ahead as the university aspires to change.

In January 2021, St. Denis was appointed special advisor to the president on anti-racism and anti-oppression to lead a strategic vision for USask to work towards its goals in equity, diversity and inclusion. In this secondment, she co-led anti-racism and anti-oppressive training for each one of USask’s senior leaders—training that was mandated by President Peter Stoicheff.

“There is literature that is starting to come out — a framework for what we need to do to have an anti-racist university — and it is validating because it’s what we have started. Scholars recommend that you have to start with the leadership, and we are doing that. And to the best of our knowledge, other universities have not done this with senior leadership … So it’s a good start, but we need to do more,” said St. Denis in an interview with On Campus News last April.

St. Denis led the training alongside senior diversity and inclusion consultant Liz Duret, an experienced facilitator in human resources with USask.

“Our work together has been transformative,” shared Duret. “Most of all we’ve developed a friendship. I have a lot of regard and respect for the hard journey that Verna’s been on doing this work — how isolating and how emotionally challenging it is. It’s probably the hardest type of scholarship to teach, because it’s so controversial and if you don’t do it in a good way, it can be very divisive.”

For Stoicheff, the process has been necessarily challenging and thought-provoking.

“Learning from Dr. St. Denis has been a privilege,” said Stoicheff. “The steps that we are taking on this journey to Indigenization, reconciliation, and decolonization are helping the university commit to meaningful change in a way that will have lasting impact. We are so fortunate to have Dr. St. Denis’s guidance on this path forward and the benefit of learning from her wisdom and her decades of experience as a leader in anti-racism scholarship.”

In early December, a dinner was hosted by the Office of the Vice-Provost Indigenous Engagement to celebrate St. Denis’s retirement and her years at the university. In addition to community members, USask staff, and educators from partner organizations, the room was packed with her former graduate students, with those who were unable to attend sending heartfelt messages.

Dr. Carmen Gillies (PhD), now assistant professor in the Department of Educational Foundations, began her learning in anti-racist education as a graduate student supervised by St. Denis. Gillies has been deeply influenced by St. Denis’s body of scholarly work, particularly her publication arguing for the necessity of critical anti-racist education in Indigenous education.

“I think Verna has really changed the conversation by demonstrating that challenging racism and white structural advantages is essential to the work of decolonization,” said Gillies. “In Saskatoon and beyond, she has created a community of anti-racist educators and that is a legacy that benefits everyone.”

St. Denis has meant a lot to the students she has mentored over the years.

“It didn’t matter if you were white, Indigenous, a person of colour, or multi-racial, she put the same amount of time into each of us, recognizing that we had different lessons to learn,” said Gillies. “As a Métis woman, I am indebted to, and inspired by Verna. She has validated our place as anti-racist and critical race scholars in academia—that our research and scholarship is important. She has challenged those binaries of you’re either working in western or Indigenous paradigms.”

Since the supper organized many years ago by her mother to help her pursue the path of higher education, St. Denis has embraced the learning experience.

“This place will always have a special spot in my heart,” said St. Denis. “I grew up here. I came when I was 20. And I never imagined that I would spend a good part of my life here. It’s been an honour.”