Asian Heritage Month: From the Philippines to Saskatoon, USask plant scientist grows connections

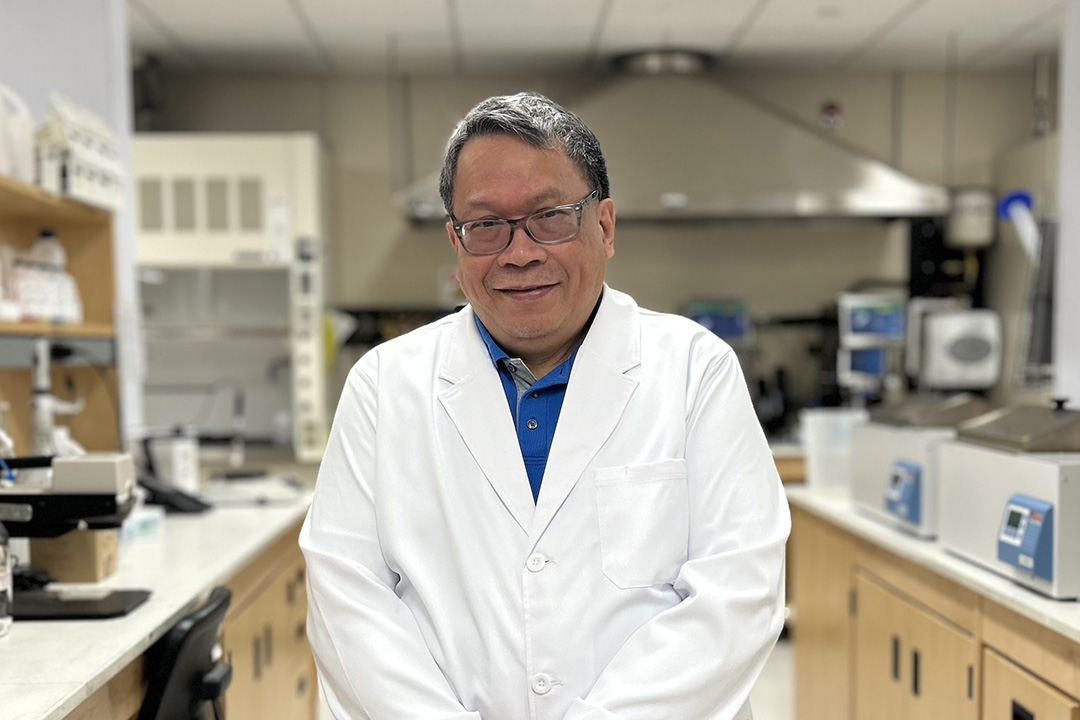

College of Agriculture and Bioresources researcher celebrates 30 years at the University of Saskatchewan (USask).

By Joanne PaulsonThe thing you notice after chatting for a while with Dr. Gene Arganosa (PhD) is his lifelong ability to create and maintain human connections.

Case in point: A connection Arganosa made while working on his first degree — a Bachelor of Science in Agricultural Chemistry — at U.P. Los Baños in the country of his birth, the Philippines, was pivotal in his journey to the University of Saskatchewan (USask).

“It was during my first semester I had this really good teacher in chemistry, and she was the one who got me interested in chemistry,” said Arganosa, a research officer with the College of Agriculture and Bioresources at USask.

“I just wrote to her, 50 years later, thanking her personally before it’s too late: ‘It was because of you that I actually shifted into chemistry.’ She remembered who I was, 50 years later.”

Arganosa, who has now been at USask for 30 years, has formed those connections over three nations.

His parents moved to the United States when he was a child to pursue their own advanced educations. He spent Grades 1 through 3 in Stillwater, Okla., before the family returned to the Philippines. He still has a Facebook friend from that time in the United States.

Years later, he returned to North America to Stillwater’s Oklahoma State University to take his second degree, a master’s in food science.

“The main reason why I chose to go to Oklahoma State was because both of my parents got their doctorate degrees there – my father in animal science and my mother in food science,” he said. “It was a family thing.”

He then completed his PhD in food science at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge, followed by a post-doc in food science and technology at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Va.

It was there that his Canadian future began to take shape, when he was at the stage in his life where he had completed his academic achievements.

“I went to the library and there was a magazine for the Canadian Institute for Food Science and Technology,” he recalled.

“At that time, the heads of the different food science and technology departments across Canada would meet. They had a picture there in one of their issues, and so I took note of their names, and I wrote to each and every one of them.”

Two people wrote back. One was Dr. Fred Wolfe (PhD), then in the Department of Food Science at the University of Alberta (U of A) in Edmonton, and the other was Dr. Alan McCurdy (PhD), head of the Department of Food Science at USask.

Wolfe had a research associate position available and offered it to Arganosa, who promptly applied for a Canadian work permit.

“But they (the Canadian Embassy in Washington) declined my application simply because I had previously applied to the Department of Food Science at Memorial University in St. John’s (N.L.). I told Fred about that, and he was very kind. He said ‘OK, Gene, I’ll help you out.’

“He was generous and I’m grateful to him for helping me obtain my permanent residency in Canada. That’s how I ended up at the U of A.”

While still in Blacksburg, Arganosa was also thinking about his personal future.

“I think I was maybe in the nesting stage looking for a spouse,” he says now, looking back.

Through the roommate he had at the time, Arganosa was introduced to a young woman named Jasmiene, who was teaching English at Central Philippine University.

“I started corresponding with her as a pen pal. Once I moved to U of A and got my permanent residency, I thought it might be time to tie the knot,” Arganosa said.

“I was with my friends at the U of A, and I told them one day, I’m going home to get married. I booked a flight and flew home and met my wife for the first time on a Friday and by the following Monday we got married. We’ve been married 32 years now.”

Three years after arriving in Alberta, where Arganosa largely worked in Lacombe, Wolfe announced his retirement. It was time to move on.

“That’s when I got hold of (Dr.) Frank Sosulski (PhD) here,” who was in the then-named Department of Crop Science and Plant Ecology. “He got hold of my resume which I had originally submitted to Al McCurdy.

“It’s amazing how in any field, I think it’s important that you build these connections. Sooner or later, you’re going to have an interaction.”

The timing proved a little tricky: when they left Edmonton, Jasmiene was eight months pregnant. Three weeks after settling in their first home, their first son, Joshua, was born.

The Arganosa family has been in Saskatoon ever since.

When he first started his present position in 1998, five years after arriving at USask, he largely worked with barley and pulse crops. After a colleague’s retirement about eight years ago, there was a reorganization, and he continued with pulses but started working on flax instead of barley.

“I do some research. On paper I’m a research officer. In reality, I look at myself more as a lab manager responsible for the chemistry lab here at the Grains and Innovation Lab. I kind of supervise the analysis related to either pulse crops or flax.”

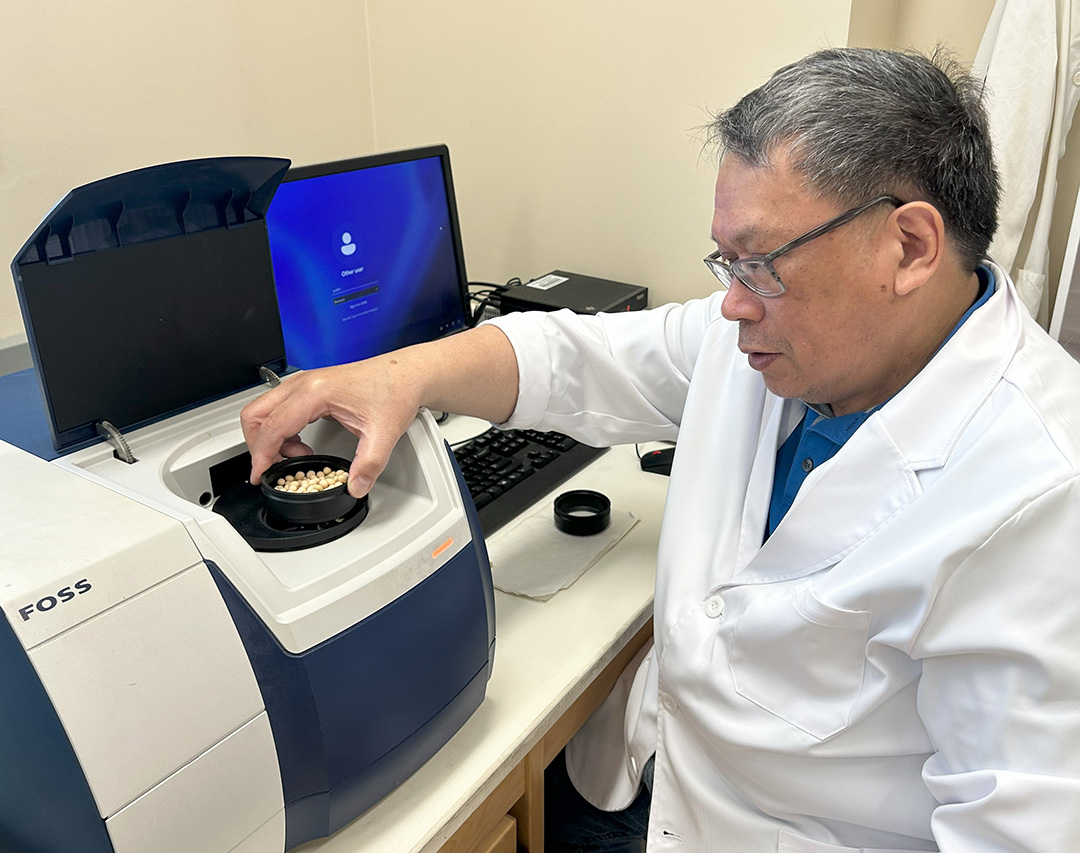

Asked what his work entails, he gave the example of how his group analyzes peas.

“One of the things for peas we like to read for is protein. We actually plant lines in as early as the last week or April or first week of May; so many lines of peas. Come harvest time, as early as maybe late August, once the lines are threshed and cleaned, we analyze them for protein using the instruments that we have.”

The lab provides the pea protein data to Dr. Tom Warkentin (PhD), the pea and soybean breeder at the Crop Development Centre. Based on the information — along with other agronomic and disease data — Warkentin determines which of the lines should be eliminated and which will be selected and planted for another season.

“It’s a long process,” Arganosa said. “Once you have a particular pea variety that’s been selected, it goes through co-op trials and regional trials.”

Each year the research team presents select varieties for registration.

“If it’s recommended for registration and it’s approved, certain seed companies would determine, OK, I like this particular new variety of peas and maybe we can pick up the right to breed this. They eventually breed that to increase the amount, and that’s the one available to the farmers.”

He enjoys his work but also his city. Connections brought him here, and now, they keep him here.

“I love it here and I love my life,” Arganosa said. “There’s no reason to leave. I’m originally from the Philippines, but then both of my parents are deceased, I’m an only child, so there’s no one for me to go back to in the Philippines.

“I’m married. Jasmiene and Joshua are here while our younger adult son, Gavriel, is in Ottawa. Jasmiene has two siblings and four nieces here in the city. So, since I’m an only child, I consider them to be as my only extended family. And we’re all here.”

And the university feels like home, too.

“I’ve been in the department for 30 years now. I actually have proof,” he said with a laugh. “I got a watch for 25 years of service.”

Together, we will undertake the research the world needs. We invite you to join by supporting critical research at USask.