USask researcher uses advanced modelling to forecast future freshwater on the Prairies

University of Saskatchewan (USask) hydrology expert Dr. Saman Razavi (PhD) is reshaping how we understand rain and snow events across the Prairies.

By Amy Janzen, SENS CommunicationsWhat if you could tell how beneficial every drop of rain or flake of snow would be for the upcoming year—before it even hits the ground?

What if, once it starts to flow downstream, you could follow those droplets as they wind their way toward a reservoir or lake, predicting how they’ll shape the environment in the months ahead?

That’s the kind of insight Razavi, an associate professor with USask’s School of Environment and Sustainability (SENS) and a member of the Global Institute for Water Security (GIWS) is working toward. Razavi studies how water moves through and interacts with both natural and human systems. His research helps communities, governments, and industries understand how extreme weather patterns will play out and how they may need to adapt.

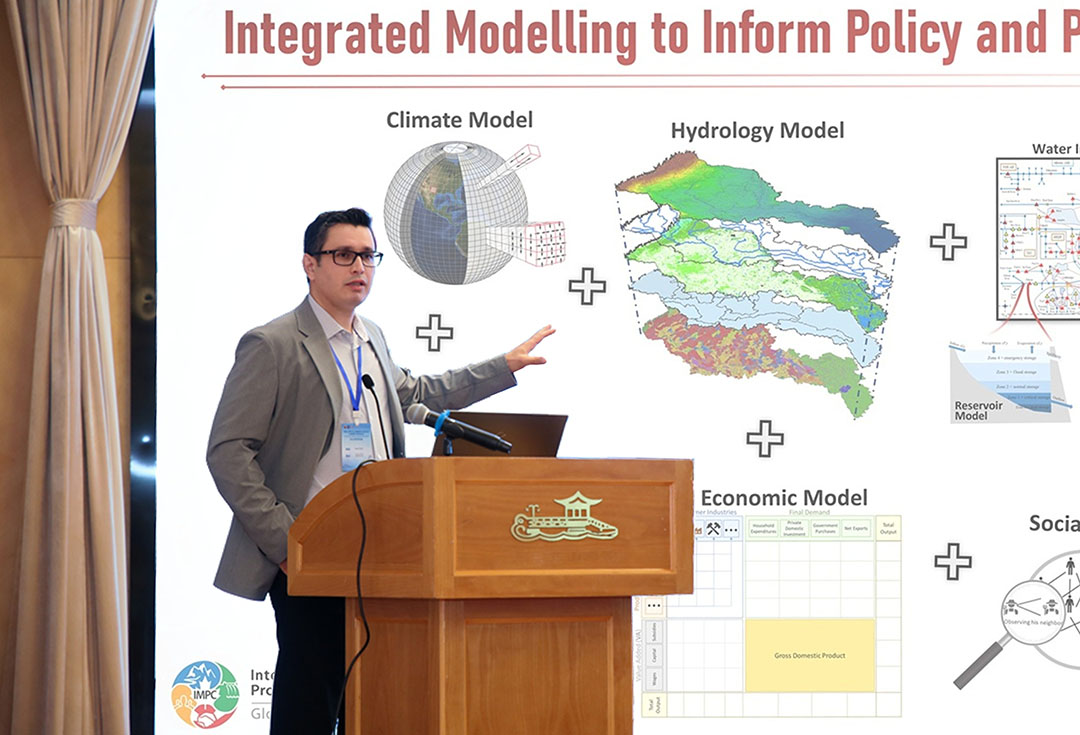

Razavi is a leading researcher in hydrology and water-systems modelling, developing advanced computer models and artificial intelligence tools to analyze the movement of water from the moment precipitation forms to when it’s stored or released downstream.

“My models look at both natural processes and human-driven processes with the objective of improving our ability to predict the future of water resources and identify how best they can be managed,” said Razavi. “We can estimate how much water we’ll get in the next hour, the next day, even the next month or season and beyond.”

What once seemed like steady seasonal rhythms of snow, melt, and water flows is changing rapidly. In Saskatchewan, a province known as much for its endless skies as its variable weather, understanding these shifting patterns is essential.

“What we’re seeing in central Saskatchewan is more pronounced swings in precipitation,” Razavi explained. “A decade ago, snowfall tended to arrive earlier in the winter and persist into March or April. Now the snow season is shorter and more variable, with more frequent winter warm-spells, earlier melt, and increasingly unpredictable transitions between snow and rain.”

But what’s important isn’t just ‘when’ Saskatchewan receives precipitation but also ‘what type’ and ‘how much’ that will impact the environment and communities.

Saskatchewan receives roughly 400 millimetres of precipitation on average each year—among the lowest in Canada—most of it arriving during the summer months. Yet this dry province remains one of the country’s major food baskets.

Snowpack is critical for replenishing rivers and reservoirs, and it also plays a vital role in recharging soil moisture that supports agriculture—but it’s just one part of the equation. Long stretches of dry weather, combined with late or short-lived snow seasons, have contributed to increasingly severe drought conditions and some of the most intense wildfire years in recent memory.

Razavi studies how these shifts affect what he calls ‘blue’ and ‘green’ water across the Prairies. Blue water is the snowmelt and runoff that eventually fills rivers, lakes, and reservoirs. Green water is the moisture held in the soil—coming from both local snowmelts soaking into the ground and rainfall during the growing season—that supports crops and natural vegetation.

“Dryland agriculture depends heavily on green water being available at the right time,” Razavi said. “Early in the cropping season, crops rely on soil moisture from melting snow, and later in the season farmers depend on timely summer rainfall.”

But these timings are shifting. Late snowfalls, changing freeze–thaw cycles, and earlier snowmelt are pushing the spring freshet—the surge in river flow driven mainly by snow and river ice melting—to earlier in the year, reducing summer blue water and putting additional pressure on ecosystems and agriculture. In the North, reduced snowpack and changes in summer storm patterns are increasing the risk of wildfires.

Despite these challenges, Razavi sees reasons for optimism.

The geographic landscape of Saskatchewan is vast, and central Saskatchewan relies just as much on local precipitation as it does on precipitation in the Rockies—especially when considering the South Saskatchewan River. At the same time, water governance in the region is gradually shifting toward a more integrated, one-basin approach, with growing investment in water infrastructure aimed at building a more resilient future.

“You might have a dry Prairie year but a wet year in the Rockies, or vice versa,” Razavi said. “What we need are smarter water-management tools and adaptive decision-making frameworks that can capitalize on these spatial differences in water availability to strengthen system resilience.”

As Saskatchewan looks to expand irrigation and strengthen water management strategies, Razavi’s work becomes even more important. He’s exploring the idea of a water decision centre in Saskatoon, essentially a hub where scientists, policymakers, and the public can come together to understand and act on real-time water data.

“This idea has been evolving over several years through both my work on the Integrated Modelling Program for Canada, which was led at USask under the Global Water Futures framework, and through related international collaborations in the United States and Australia,” said Razavi. “But it really started to take shape this past summer when concerns over the unusually low water levels in the South Saskatchewan River drew heightened attention about the cause of the low depth, from both local leaders and the public. It became quite clear that what Saskatoon could really use is an information hub.”

Razavi envisions a place where advanced water models are accessible to stakeholders and the public. In this space, users could simulate different decision options, see the trade-offs, and understand how choices in one place may affect other places across the whole water system.

It would help people explore how climate change influences water, ecosystems, and agriculture, while serving as a bridge between government, scientists, and the community to co-develop resilient solutions and build trust in the science behind water decisions.

Thanks to GIWS, USask is home to the highest concentration of the world’s leading researchers tackling water issues from every angle. He sees this investment as vitally important as we build a more sustainable water future for the Prairies and Canada.

For Razavi, water research is more than modelling. It’s about building resilience by helping people across sectors anticipate what’s next and make smarter decisions in the face of change.

His research is woven into graduate student training within SENS, a research-intensive graduate school rooted in community engagement and interdisciplinary research that serves as a catalyst for bringing the best and brightest to USask and training the next generation of water scientists and professionals to tackle water security challenges across the Prairies, Canada, and beyond.