Carnivorous plants among impressive herbarium collection

Hugo Cota-Sanchez fills a small jar from a sink in his office and sets it on his desk, then retrieves the wizened remains of a plant from another jar. With its fronds tightly curled like a fist and with a few small dry roots, it seems death has long since claimed it and it could easily be crushed into powder.

By Michael Robin "This is a resurrection plant," said Cota-Sanchez as he places it in the water. "I use it to teach my students."

"This is a resurrection plant," said Cota-Sanchez as he places it in the water. "I use it to teach my students."He explained Selaginella lepidophylla is from a family of plants known as spikemosses, an ancient evolutionary branch of life that pre-dates flowering plants. Supremely adapted to dry conditions, it can lie dormant for decades, waiting for a rare rain to unfurl its fronds and begin growing again.

Cota-Sanchez is an associate professor of biology—more specifically, botany—and curator of the W.P. Fraser Herbarium. The herbarium includes plant samples collected over decades from all over Saskatchewan.

Cota-Sanchez's love of plants and the uses humans make of them is evident in his office décor. A decorative owl carved from a fist-sized fibrous seed competes for shelf space with similar monkey-head carvings from coconuts, a loofah sponge and a fishing net made from willow roots.

Among the collection is "Mr. Bioscan," who figured prominently in the annual Bioscan Science Fair for school children hosted by the College of Arts and Science. The simple mannequin with a coconut head and straw hat wears an all-natural burlap suit. Cota-Sanchez sometimes wears the suit in class to demonstrate plants' versatility.

He explained the key to plants' usefulness in everything from building houses to weaving fine linens comes down to one molecule: cellulose. Plants use it to stiffen their stems, create lightweight fibres to carry their seeds on the wind, and grow roots strong enough to penetrate soil and even cracks in rock.

"Cellulose is the most abundant polymer on Earth and its tensile strength rivals that of steel," Cota-Sanchez said, as he leads the way to the herbarium in the College of Agriculture and Bioresources.

This visit is focused on a different marvel: carnivorous plants. Typically found in bogs, Cota-Sanchez said these plants survive in what is essentially a "wet desert," a place where there is plenty of water but it's hard to use, and there are few nutrients available.

"It (the water) is highly acidic and plants need more nutrients than what is available there, so very few can survive," he said. "They are very specialized. We see many adaptations like very tough leaves."

Carnivorous plants' adaptations make up for the nutrient-poor environment by luring and trapping insects. The bugs' proteins, once digested, make a good source of nitrogen and phosphorus. There are three types of these plants native to Saskatchewan: sundews, bladderworts and pitcher plants. Each has evolved a different strategy to catch their meals, he explained.

Sundews grow slender leaves covered with hair-like tentacles, each tipped with a droplet of sticky, sweet liquid loaded with enzymes to digest insects once they have been lured and trapped.

Bladderworts, as their name suggests, feature bladders that literally suck in aquatic insect prey in much the same way that a turkey baster sucks in fluid when its bulb is squeezed and released.

Pitcher plants' name also suggests their trapping strategy: a liquid-filled pitcher whose inner surface features inward-pointing hairs that ensure that once prey climbs in, it can't climb out.

Like most northern plants, Saskatchewan's carnivorous flora are small, limited by available sunlight and growing season, and have restricted geographic distribution. For example, the largest tropical pitcher plants are big enough to hold more than a litre of liquid and catch not only insects but small animals like shrews. Pitchers growing in Saskatchewan bogs are about as long as a man's finger.

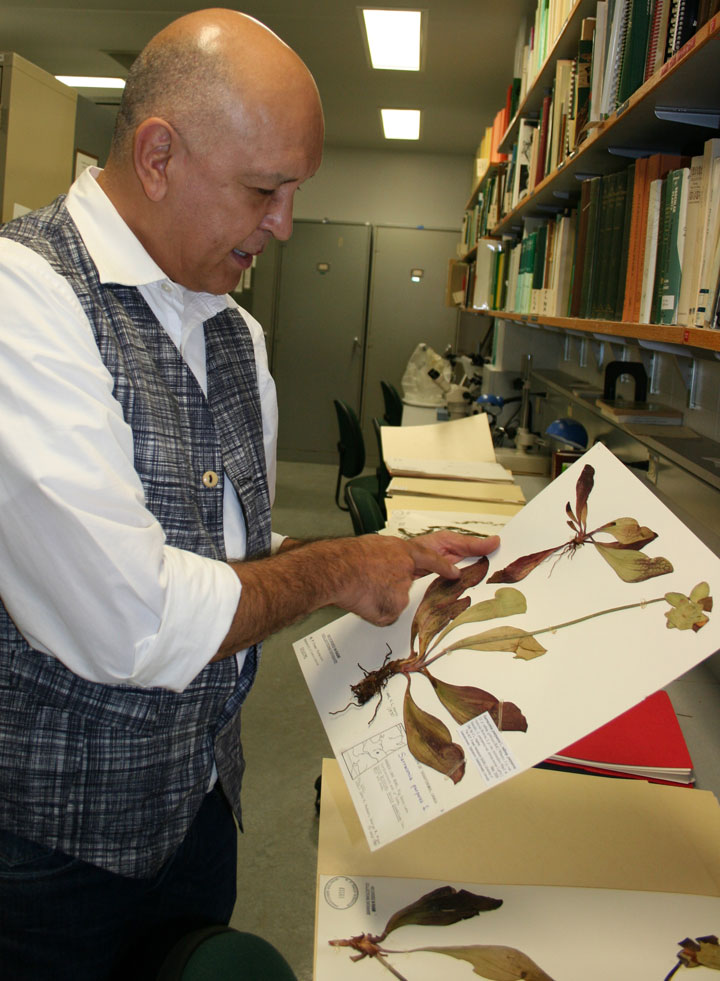

There are specimens of all three types of carnivorous plants at the W.P. Fraser Herbarium, carefully collected from locations chiefly in central and northern Saskatchewan.

Each specimen is pressed, dried and mounted on paper with information like where it was gathered, what plants were growing around it, in what landforms it was found, and the collector's number. Cota-Sanchez said every botanist is issued a unique number for collecting; some can gather 40,000 to 50,000 specimens in a career. The herbarium is home to several lifetimes of work.

"Our collection specializes in the flora of Saskatchewan," Cota-Sanchez said. "I would say 80 per cent of our specimens are from Saskatchewan and our collection here has nearly 182,000 specimens."

Those specimens are stored in rank after rank of two-metre-high steel cabinets. More than a botanical library, Cota-Sanchez explained the value of the collection: it represents Saskatchewan's past and present plant diversity and it is source material. Researchers are constantly finding new ways to use it. For example, they have extracted DNA from herbarium specimens gathered in the 1940s, demonstrating that genetic information is also included in the collection.

"We get a lot of requests from different Canadian and United States herbaria for specimens," Cota-Sanchez said. "We trade or lend specimens for scientific research."

Cota-Sanchez and his colleagues also have their own project, using the herbarium as reference to create a comprehensive catalog of plants in Saskatchewan intended to replace a similar work on Alberta flora that students must now use. It's a mammoth task, so the team has split the project into four sections of a single book, each published separately. So far, three are done: ferns and fern allies, lilies and orchids, and the genus Carex (sedges). The final one, on grasses, is scheduled for publication in December. The books are available at the U of S Bookstore.

On the walk back to his office, Cota-Sanchez confessed to being a bit of a "plant geek," which has interesting side benefits. When watching a movie set in Africa, he immediately saw through the film maker's ruse as he recognized the flora of California. Likewise, in the movie Jurassic Park, a character holds up a plant and declares it to be one of the first land plants.

"It was actually a begonia," Cota-Sanchez said – a fairly recent species from an evolutionary standpoint. "Botanically speaking, she made a very bad mistake."

Back at the office, the resurrection plant has already begun to unfurl its fronds. Cota-Sanchez plucks it from its jar of water to return it to dormancy, its lesson conveyed: plants, with their infinite variety and tenacity, are miraculous creatures that sustain and make possible life on Earth.