Getting to the heart of arrhythmia

Scientists using X-rays at the Canadian Light Source (CLS) synchrotron have reconstructed the scenario of heart arrhythmia in action, an important step toward preventing the deadly condition and saving lives.

By Kris Foster A CLS release said a 3D model was created using images from the CLS that revealed for the first time how gene mutations affect the pathway in heart muscle cells that control its rhythm. Arrhythmias are the heart beating too fast, too slow or inconsistently, causing a decrease in blood flow to the brain and body that results in heart palpitations, dizziness, fainting or even death.

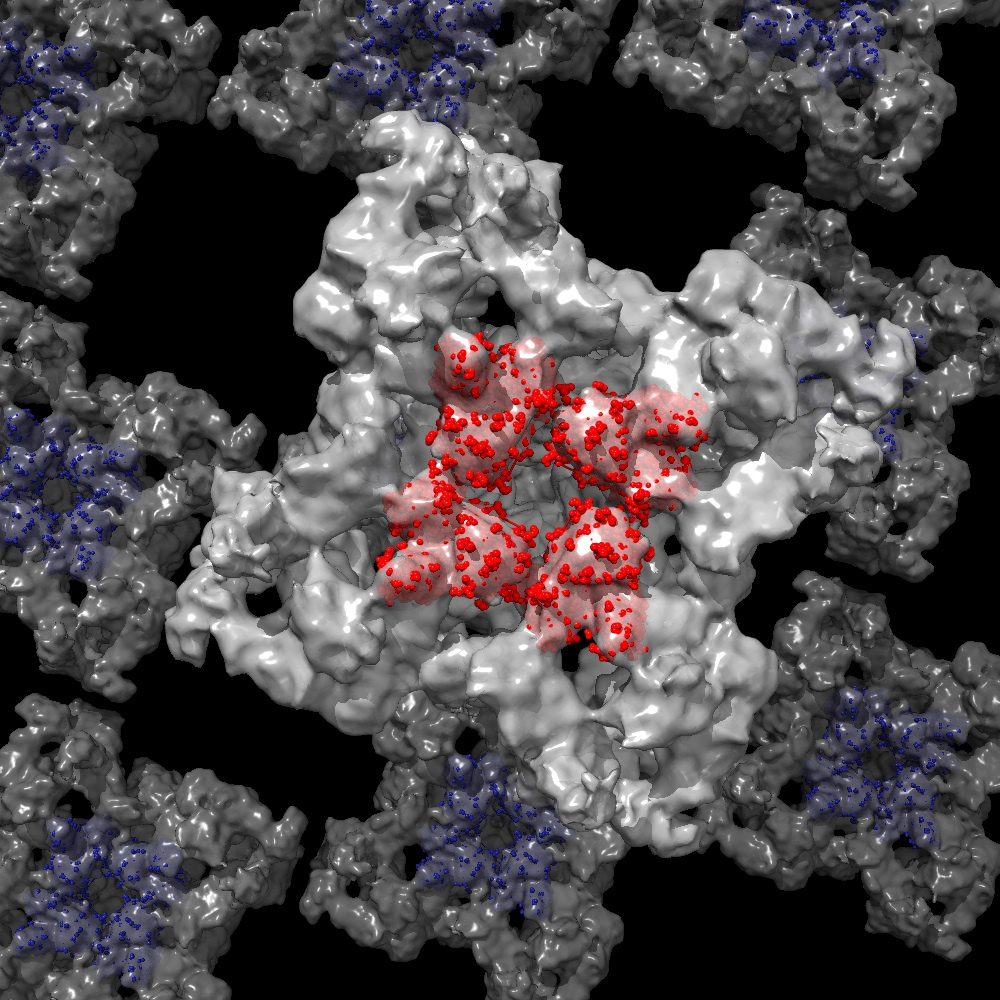

A CLS release said a 3D model was created using images from the CLS that revealed for the first time how gene mutations affect the pathway in heart muscle cells that control its rhythm. Arrhythmias are the heart beating too fast, too slow or inconsistently, causing a decrease in blood flow to the brain and body that results in heart palpitations, dizziness, fainting or even death.The research, done by Filip Van Petegem, molecular biologist from the University of British Columbia, was published in the journal Nature Communications and presented at the recent 2013 annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

According to the published article, the heart runs on calcium and every heartbeat is preceded by calcium ions rushing into heart muscle cells. Then, a special protein opens the pathway for calcium to be released from compartments within those cells, and in turn, initiates the heart muscle contraction. Mutations to this protein have been linked to arrhythmia and sudden cardiac deaths in otherwise healthy people.

"We analyzed several disease mutant forms of a specific calcium channel that has been linked to cardiac arrhythmias," said Van Petegem. "Thanks to the 3D reconstruction of these new mutant structures, it allows us to look at the detailed effects of each genetic disease mutation."

Van Petegem said that many heart diseases cause much larger structural changes than he originally anticipated, and that could directly explain their effect on calcium leaking into the muscle cell and causing arrhythmias. He is hopeful that the research will lead to new ways of stabilizing the pathway to the heart.