U of S alum John Diefenbaker and the Great War

In July of 1936, John Diefenbaker travelled with more than 6,000 other Canadians across the Atlantic to witness King Edward VIII’s dedication of the Vimy Ridge Memorial on the site where, almost two decades earlier, Canadian troops had fought for the first time as a cohesive unit under Canadian command.

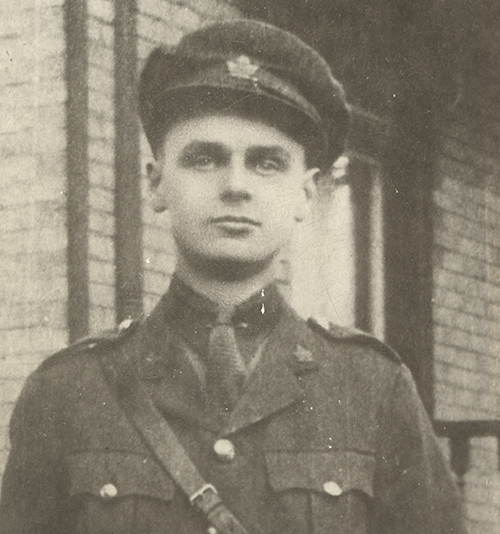

By TERESA CARLSONThroughout the 1930s, as Diefenbaker was trying to launch his political career, he did what most military veterans of that era who aspired to political office did: remind people of his overseas service in the Great War. In his biography, Diefenbaker tells of being injured in a trench while training overseas, and of being sent home to Canada before the war’s end. While this story is technically true, it does not tell the full story of Diefenbaker’s military service.

Diefenbaker enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Forces on Aug. 25, 1916, two years after the first University of Saskatchewan student and faculty recruits stepped forward to add their names to the roster of those who initially expected to return home by Christmas 1914.

Perhaps it was his heritage that gave him pause to immediately sign up (German-Canadians on the Prairies faced fierce prejudice after the First World War broke out), but the 19-year-old Diefenbaker completed his bachelor’s degree in political science and economics in 1915 at the U of S first before enlisting.

By the time Diefenbaker received his degree, he and his fellow classmates would have been reading regular updates in The Sheaf student newspaper, detailing the horrors of modern industrial warfare and the toll that it was taking on university members now overseas. After receiving his undergraduate degree, he launched into graduate studies and promptly enlisted, earning his master’s in absentia the following year.

According to his military records, it was while training in England that Diefenbaker was injured (“hit in the back with pick axe,” he wrote in his biography) while digging a practice trench. While recovering, he exhibited other symptoms that troubled physicians—easily becoming short of breath and occasionally bleeding from the mouth after mild to moderate exertion.

Several months later, he was diagnosed with cardiac disease and described as “unable to climb a hill or do physical training, owing to dyspnea [shortness of breath] and general weakness.” He was declared physically unfit, and a year after his enlistment, he returned to the U of S where he enrolled in the College of Law.

Both Diefenbaker’s injuries and illnesses during the Great War, and not being able to serve on the battlefield, clearly haunted him. Reflecting back on his military service record in 1969, Diefenbaker said “I wouldn’t be here, no possibility; the possibility is so remote. We went overseas with 182 lieutenants and 12 weeks later there were 33 living. Utter slaughter. Young officers going over the top.”

What Diefenbaker learned from his military service seems to have motivated him on subsequent occasions.

After graduating from the U of S with a law degree in 1919, Diefenbaker spent much of the rest of his life defending human rights. He was an outspoken advocate of the rights of the average Canadian and ethnic minorities, and while serving as Prime Minister he broke with American policy and opened trade relations with Communist China and refused to support U.S. hostilities against Cuba. In the Commonwealth, he supported the aspirations of non-white colonies to gain independence and led the organization’s opposition to Apartheid in South Africa.

Diefenbaker, it seemed, wanted to make the most of surviving the Great War years, by fighting the social injustices that persisted after it.