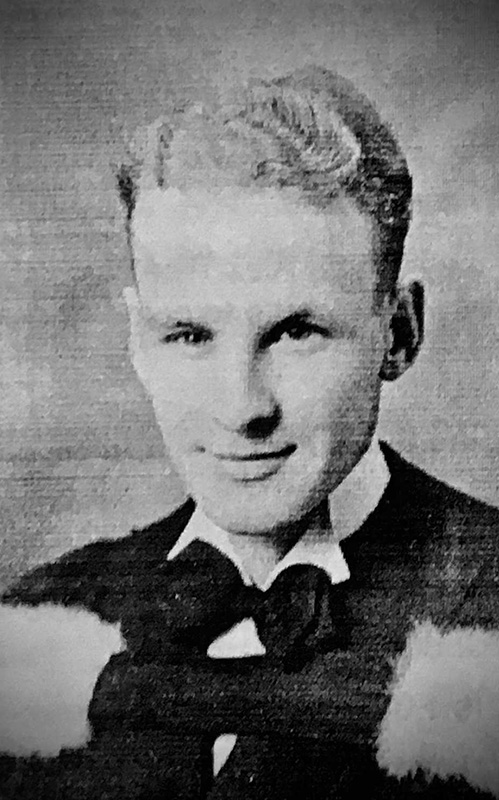

Service and sacrifice: Remembering USask law student who gave his life in Second World War

He grew up on the family farm near Harris, 80 kilometres southwest of Saskatoon where he went to earn a bachelor’s degree at the University of Saskatchewan (USask) before heading off to war.

By James ShewagaToday, John Alexander (Sandy) Hanley lies at rest 8,000 kilometres away in the Cassino War Cemetery in Italy, one of the 2,500 USask students, staff and faculty who served in the Second World War and one of the 202 who never came home.

For the Hanley family, there is a solemn sense of pride in his service and his sacrifice, and the choice he made to leave law school in order to volunteer to serve his country.

“We are really proud of him for doing that,” said Janaya Hanley, who has dedicated her free time during the pandemic to researching her great uncle’s life and death. “He was very young. He was barely 28 when he died and just thinking about that, I am 27 now, and it is difficult to imagine having that much responsibility. He was a captain overseas, so he was a troop commander. To be so young and to be responsible for all of these other men in your troop is quite something.”

Sandy Hanley entered USask in 1937 and earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1940 before enrolling in law school. A strong student and athlete, he played rugby and water polo for university teams, and was an active student leader, serving as president of the Newman Club, the university’s Catholic student society. Sandy could have continued his studies and started a successful career as a lawyer and perhaps a judge one day, but instead joined Canadians from coast to coast who answered the call to duty, and one of the more than 45,000 who paid the ultimate price.

As noted by Patrick Hayes of University Archives and Special Collections, it was a different era, a time when the war effort galvanized the entire country to do its part. USask was no exception, with patriotic students like Sandy joining the university’s Canadian Officers Training Corps program to prepare for a world at war.

“The world would be a very different place had the Allies not won the Second World War,” said Hayes. “They fought against an enemy that was anti-democratic and preached racial superiority. All our freedoms—speech, assembly, religion and the ability to have a say in how we are governed—were under attack. The reality of the threat was evident to all. Even with the end of The Great War in 1918, a second war was seen as inevitable. USask was at the forefront of Canadian preparedness for the next conflict.”

Sandy was among those ready to do their part. In September 1940, he left university to join the Royal Canadian Artillery, trained and headed overseas to join the front lines in the gruelling two-year Allied campaign in Italy. On May 30, 1944, in the push towards Rome, he was crossing the Melfa River under withering fire when his tank was hit by a German shell and he was killed instantly. Five days later the Allies reached Rome on June 4, two days before the D-Day landings turned the tide of the war.

“The battle of Monte Cassino spanned quite a few months and it was really the last push to get to Rome,” said Janaya, who grew up in Kindersley and now lives in Regina. “Not only did they need Rome from a tactical perspective, but it was also very symbolic to liberate Rome. So many Canadians gave their lives, but there is pride in knowing that Sandy played a role in that crucial part of the war.”

Sandy’s brother Robert also served overseas with the Royal Canadian Air Force, and recently passed away just shy of his 100th birthday. Both brothers were highly decorated, earning multiple medals for their service during the Second World War.

Sandy is one of the 855 Canadian soldiers buried in the historic Cassino War Cemetery, situated in a picturesque now peaceful valley at the foot of a towering hill topped by the majestic medieval Abbey of Monte Cassino, founded back in the year 529. Over the centuries it has been destroyed and rebuilt multiple times after multiple battles, including during the Second World War, just weeks before Sandy was killed in action.

Tracing his steps and his story has become a passion and point of pride for his great niece and nephews.

“To be honest, I didn’t know a lot about Sandy growing up, but I’m proud that we are able to do this research now,” said Janaya, noting that Hanley Lake in northern Saskatchewan is named after her great uncle, one of a number of provincial lakes named after soldiers who gave their lives in the Second World War. “Sandy didn’t have any kids, so it is nice that we can try to remember him in this way.”