Uniquely USask: A priceless treasure trove of shooting stars

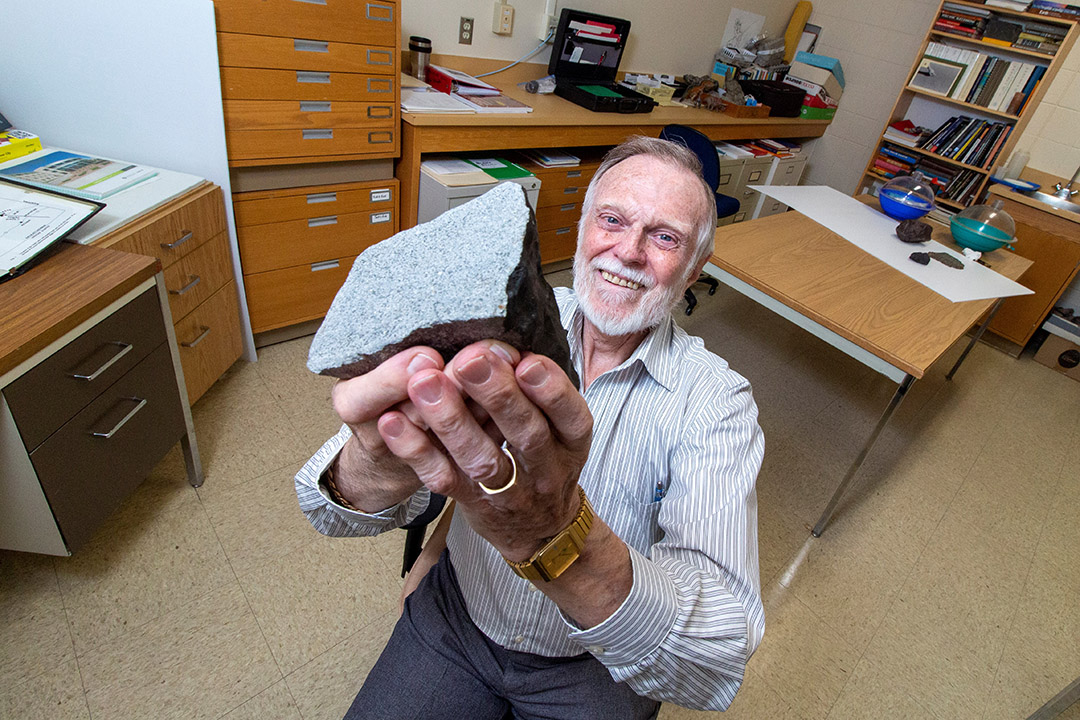

From a worn cardboard tray locked away in the Geology Building, Dr. Mel Stauffer (PhD) retrieves a lump of the most valuable space rock on Earth.

By Chris PutnamFinding even one meteorite in nature is “an awful long shot,” said Stauffer. The multitude of meteorites in this room—brought together from across billions of kilometers of space—is closer to a miracle.

Stauffer, a professor emeritus of geology in the University of Saskatchewan (USask) College of Arts and Science, is holding a palm-sized, 270-gram piece of the Murchison meteorite. The Murchison—which fell in Australia in 1969—is among the world’s most scientifically important meteorites due to the rich organic compounds it contains.

“They’ve found a whole lot of amino acids in (Murchison fragments), including some, I understand, that are involved with life,” said Stauffer. Those findings lend growing evidence that the building blocks of life could have arrived on Earth aboard ancient meteorites.

The Murchison’s skyrocketing scientific value has driven up its monetary value. USask purchased its piece for less than $200 in the early 1970s. Smaller fragments now sell online for thousands of dollars per gram.

The Murchison is special, but Stauffer’s favourite specimens are from closer to home. Fewer than 20 meteorites have been found in Saskatchewan, and pieces from six of them are in the USask collection. In 1981, Stauffer interviewed surviving witnesses to the Saskatchewan fireball of 1922, a brilliant meteor sighted near the town of Wynyard, Sask. Nearly 60 years later, their memories of the event remained bright.

“Everybody we talked to remembered exactly where they were standing, exactly what direction they were looking, exactly how far up in the sky they saw it,” said Stauffer.

Based on those reports, Stauffer and Dr. Don Gendzwill (PhD) tracked down a possible fragment of the Saskatchewan fireball found years earlier by a local farmer. That meteorite was taken for analysis to USask, where a plaster cast and slice of the original are now kept.

The university’s unique collection also includes fragments of the Buzzard Coulee, the province’s only recovered meteorite known to have been observed while falling. Stauffer was among dozens of searchers who found pieces when it fell near the province’s western border in 2008.

Meteorite hunting, Stauffer admits, is usually “boring as all hell. You walk across the ground looking at things, and mostly you don’t see meteorites.”

But the excitement of those rare finds keeps him coming back.

“I don’t know how many meteorite specimens I’ve found in my life now—several dozen,” he said. “Each one’s as much a thrill as the first.”