Going global in search of answers

People often ask John Giesy why he spends so much time working in Hong Kong, China, considering he’s a Canada Research Chair in Environmental Toxicology.

By HenryTye GlazebrookHis answer is always simple.

“I can affect our environment more by the work I do in China than here,” said Giesy, who holds multiple professorships in China and was the second Canadian ever to be awarded the Einstein Professor of the Chinese Academy of Science. “What happens in China goes around and comes around. What they release in China ends up in polar bears in our Canadian Arctic, and our Northern people get exposed through their diet to these things even though they’re getting no economic benefit from the manufacture or use of them.”

Giesy is a man of many accomplishments. He has dual citizenship and high-level security clearances with both Canada and the United States, where his expertise has been sought on everything from the public safety of chemicals to the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico.

In the 1970s he worked in Vietnam to better understand the use of Agent Orange, which contains a highly toxic component known as dioxin, helping to broker negotiations between the Asia-Pacific nation and the United States.

His list of accredited citations sprawls vastly, as high as 55,000, making him one of the foremost experts in the combined fields of environment and environmental toxicology.

He’s also a professor in the Department of Veterinary Biomedical Sciences and Toxicology Centre at the University of Saskatchewan, where he does research and instructs students.

It’s that last area where Giesy thinks his main duty lies, not just to U of S students but to fellow researchers, politicians and the everyday citizens of Canada.

“We’re in the education business,” he said. “There are a lot of great scientists, but what makes the difference, I think, between just being a scientist and being what I inspire to be as a Canada Research Chair, is being able to translate into social welfare, being able to explain it to the public, to have it have implications. It’s all about education.”

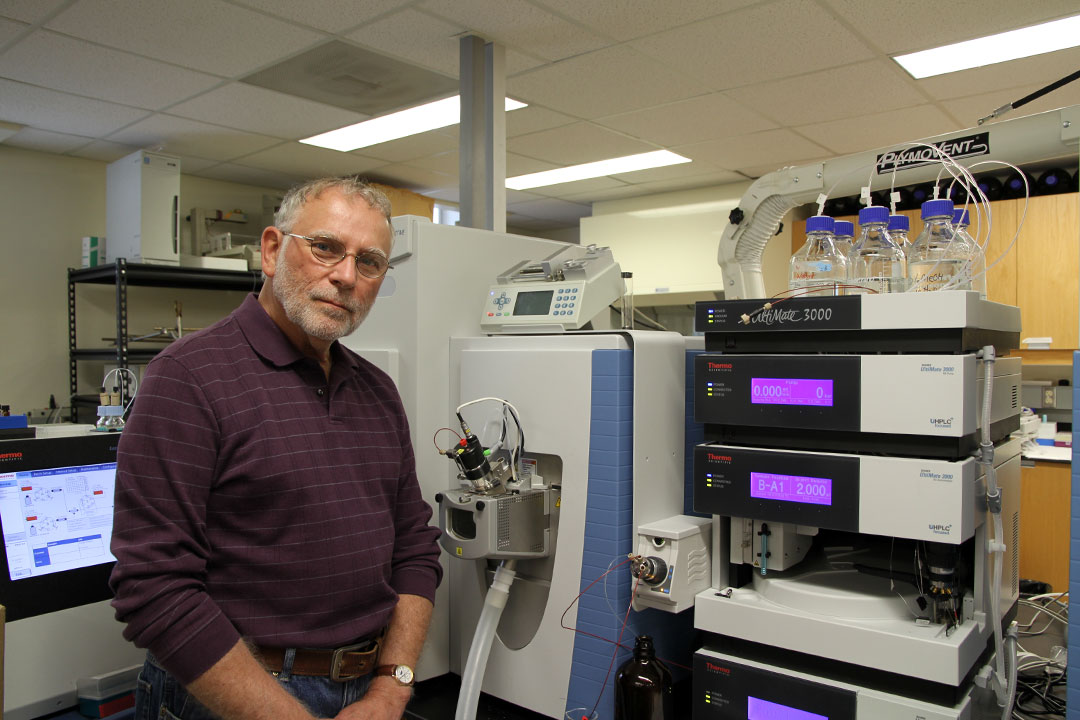

Giesy works in mass spectrometry, a very technical sounding term regarding chemical analysis that he likes to explain as “socially relevant research.” Some of his projects are thought up by himself and his colleagues while others are brought to him by governmental leaders, but all involve exploring the near-unnoticeable pieces that make up our world.

The key, he said, is identifying what may or may not be harmful to humans and helping others use that information to manage the risk in their lives.

He cited the common potato as an example of understanding risk. These everyday root vegetables are technically in the deadly nightshade family due to the natural toxins they contain, developed to deter insects from feasting on them, and yet remain a staple of meals across the globe.

“The bottom line is there are risks to everything you do,” Giesy said. “Talking to me is technically a risk—the office could be hit by lightning—but it’s a relatively small risk, based on our experience. My job is to put those risks in perspective for you. We don’t want you so afraid of everything that you can’t live your life.”

Today Giesy is working in the Athabasca and South Saskatchewan River Basin, where he wants to educate communities about the safety of the food located right in their backyard to help curb rising issues of obesity and diabetes due to poor nutrition.

The concern of the local populace is that oil sand developments and pesticide use have made fish and produce in the area unfit for consumption. The reality, said Giesy, is that much of what’s available is harmless.

“You have a risk of contaminants on the berries, but it’s pretty minor,” he said. “But the risk of not eating them, because of the loss of antioxidants and vitamin C, B, D, is huge. And that translates directly to what we see in the health of the population—obesity, diabetes, heart disease, the list just goes on and on and on. It’s not so much what they did eat, but what they didn’t eat.”

This experience falls closer to home than, say, his time in China, but the hope in any case is that he can change hearts and minds. For Giesy, it’s all about the long term, the big picture—how is today’s work going to reverberate and help make lasting, positive change?

“When I go to China, I teach short courses working with students and post-docs, but mostly with the professors to educate them in the newest technologies so they can apply it in their own research,” he said. “The idea is to multiply these things. It’s like throwing a pebble in a pond; it touches many shores.

“I can’t save the world one person at a time, but if I work with a third of the world’s population living in China I can have a big impact.”