Land and language intertwined for SENS student

Exploring the woods surrounding her Yukon home, Jocelyn Joe-Strack had an epiphany about her Western and Indigenous worlds.

By HenryTye GlazebrookShe came to realize how her ancestors only spoke of, and viewed, the forest, animals and air as alive and with spirit, how they might greet a flame with a friendly “Oh fire, you’re hungry. Let me feed you.” It was the harmony of the way her language, Southern Tutchone, implies life, rather than objectification, that spoke to her.

“The only things objectified were those that were made—so a knife, a bag, shoes, clothing—and everything else is regarded as alive, honoured and acknowledged as with spirit,” Joe-Strack said.

“I had this kind of reckoning: I walked through the forest and I felt so much more love and support than I’d ever felt before. The forest is alive and it loves us and it’s there for us.”

Joe-Strack is a PhD candidate with the University of Saskatchewan’s School of Environment and Sustainability, and one of four U of S recipients of the 2017 Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship. The award, valued at $50,000 per year for three years, recognizes top-tier PhD students who demonstrate excellence in academia, research impact and leadership at Canadian universities.

But for students like Joe-Strack, the scholarship is about more than the money or the prestige that comes with winning one of the nation’s most-coveted prizes. Instead, she’s more excited about how it will help her research thrive.

“I’m a mother and I have a family, and if it wasn’t for this scholarship, I think I would have had to continue to work as a consultant throughout my PhD and it likely would have prolonged and suffered because of it,” she said.

“Now I’m provided the opportunity to just dedicate myself and I’m really excited for that.”

The Southern Tutchone language is intricately entwined with Joe-Strack’s thesis, a three- year project that has taken her to Saskatoon and home again, where she is working with her First Nation of Champagne and Aishihik to develop a land use plan.

Joe-Strack is hoping to forge new paths in academic storytelling with her work, weaving her experience growing up in the Yukon and with her time helping plan her First Nation’s future in a first-hand, scholarly account of the community’s journey toward self-determination and Indigenous-led reconciliation. The finished product, she hopes, will be a contribution to the emerging field of Indigenous research.

“I am keeping a journal of my time with my nation and the lessons that I’m learning and reflecting upon, and preparing my thesis is going to be more of an autoethnography,” Joe-Strack said. “It’s going to be a recount of my place in this collective journey and in fulfilling my role in contributing a land plan for my people and what that means in the significance of our extended journey.”

The First Nations of the Yukon are a unique case study among Indigenous communities in that they have implemented their own self-government that exists at the same level as the Yukon Government, under the Canadian Constitution. The result is a governing body by First Nations and for First Nations that holds a higher level of autonomy than Indian Act Nations—and one that, to Joe-Strack, is worth studying and shining a light on.

“I would like to try and do my best to tie (my research) back to the global Indigenous journey of overcoming oppression, because we are one of the most successful, progressive Indigenous nations in the world.”

A land plan may seem like a rather singular project to be pulling in larger topics like language, history and governance—all while acknowledging the ongoing legacy of residential schools and the pursuit of reconciliation—but Joe-Strack would disagree.

“Our land means our culture, it means healing, it’s our connection to our language and our community and to each other,” she said. “It’s so much more than this swamp or that bay. It’s our livelihood and our identity, and a land plan should reflect that and should strengthen our community and our individual citizens’ ability to identify and find strength in being a First Nations person.”

Pelletier looks into leadership for First Nations

As a former chief of the Cowessess First Nation in Saskatchewan, Terrance Pelletier is no stranger to the leadership of Indigenous communities. Now he’s hoping to build on the experience for his PhD. Pelletier, a U of S graduate student in educational administration who was recently awarded a 2017 Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship, is exploring how the leadership models within First Nations have been influenced by the effects of colonization.

“It’s looking at the historical influences of the residential school and Indian Affairs processes and the type of influences they had on our people as leaders,” said Pelletier, who himself is a residential school survivor.

“It’s more to understand why we are the way we are today, to understand how our leaders and institutions have become the way they are today.”

Pelletier hopes that his research will help to create new leadership models for First Nations communities, and is grateful that awards such as the Vanier scholarship have made it possible for people like himself to pursue their work with financial pressures eased.

“It’s difficult, not just for First Nations people but for all graduate students, when we come here to tackle the academic rigour of each of the colleges that we’re at—to meet deadlines and things like that, but also to meet the financial obligations that we have,” he said.

Supporting Indigenous women in urban centres

When people think of Indigenous territories, a similar scene often springs to mind: paltry reservations or towns remotely located away from any city centre.

For U of S educational foundations graduate student Tasha Spillett, a Cree and Trinidadian woman from Manitoba, this idea presents a problem.

“We need to challenge the idea that urban environments and areas are not also Indigenous territories,” said Spillett, who was awarded a 2017 Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship to pursue her PhD research.

“It’s important to reconnect the people who have always been living in the city or who have been displaced from their communities, to reconnect those relationships between our land bases and our identities and for non-Indigenous people to be invited into the under- standing that these urban areas continue to be Indigenous territories, regardless of what infrastructure has been built overtop of them.” Spillett’s work is specifically focused around the well-being of Indigenous women in urban centres. Through a series of interviews with Aboriginal Elders and teenage girls in these areas, she’s hoping to curb the systemic violence against Indigenous people.

For Spillett, the Vanier scholarship is an honour that will lend greater support for her research while she supports those who she’s hoping to help most of all.

“While I did my undergraduate and my graduate degrees, I also worked full time,” she said. “This will be the first time that I can really focus on the work, the research and the study, and not also have to hold a full-time job. It means the freedom to do the work that my community has said it wants done.”

Studying steel safety in critical construction

In the event of an explosion, the protective steel that is used in the construction of chemical and nuclear plants can fracture in unpredictable ways and create critical safety issues.

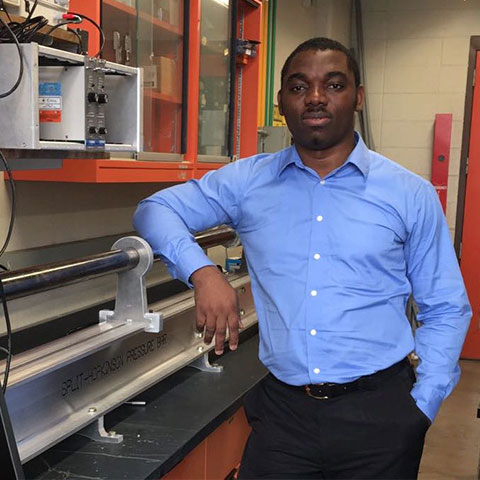

Ahmed Tiamiyu, a University of Saskatchewan mechanical engineering PhD student from Nigeria, wants to revolutionize the way that steel reacts when under pressure.

His research, which recently led to him being awarded a 2017 Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship, is aimed at optimizing an existing grade of stainless steel which would better hold up to high temperature and load-bearing circumstances.

“The aim is to improve safety,” said Tiamiyu. “Even in Canada, we’ve had some chemical plant operation errors that lead to explosions.

“This research has a good promise of improving the performance and reliability of this material in the event of an unanticipated explosion. In the long run, lives can be saved.”

Winning the Vanier scholarship has been uplifting for Tiamiyu, giving him the security of knowing his research is seen as vital beyond his own lab.

“Students do get just a little encouragement in what they do most of the time. However, this Vanier scholarship is for me a morale booster,” he said.

“I am highly encouraged that my work is gaining recognition and that what I’m doing is very important to the scientific community, to society and to the nation at large.”