The road to reconciliation: A personal story of seeking truth and healing

It was a punishing and empowering 100-mile walk over 10 days, covering traditional hunting and trading trails from Treaty 2 to Treaty 4 territory, a trip back in time tracing the steps from old Fort Ellice in Manitoba to Fort Qu’Appelle in Saskatchewan.

By James ShewagaIt was also a chance for Candace Wasacase-Lafferty to walk in her father’s footsteps, on the haunting grounds of the Birtle Residential School that took his childhood away. However, for Wasacase-Lafferty, there was one unforgettable difference.

“I got to walk away from that place, but he never had the chance to choose to leave,” she said.

It is a painful and powerful story of the tragic truth of the residential school system that ripped families apart, and left scars that remain to this day. It is also a story of one man’s determination to not let his past affect his children’s future.

“My dad never talked about residential school, and I didn’t understand the pain he went through,” said Wasacase-Lafferty, the senior director of Indigenous initiatives and community relations in the provost’s office at the University of Saskatchewan (USask). “He didn’t want to burden me with those truths and he didn’t want it to hold me back. He raised me with joy and hope and vision and dreams. I had all kinds of dreams and I still do, and he never wanted to burden me with his truth. Now, I can actually see his truth and be OK with his truth, and be stronger because of his truth.”

Candace’s father George Wasacase was one of an estimated 150,000 Indigenous children who were forcibly taken from their homes, stripped of their identity, their language and culture, with some never returning home again. Of those who did, many returned broken, forever haunted by their experiences.

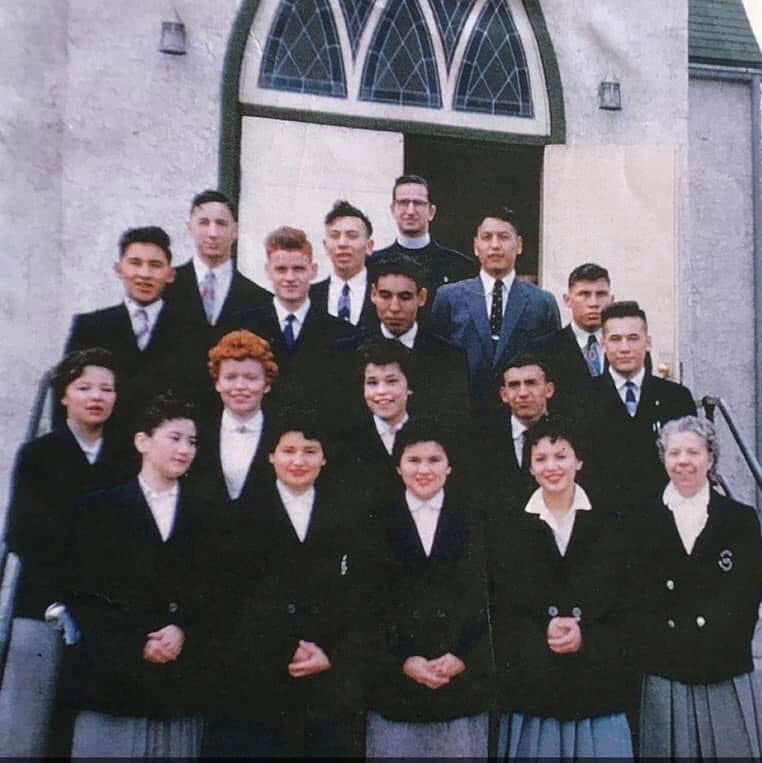

Like so many before and after him – including his cousins – George was only five years old when he was taken away from his family on Kahkewistahaw First Nation in southern Saskatchewan in the early 1940s. He would spend the next dozen years suffering in residential schools, first at nearby Round Lake, and then in Birtle in southwestern Manitoba, 130 kilometres away from home.

George was only eight years old when his mother died, with his father passing away four years later while he was again in Birtle. He was an orphan at the age of 12, forced to remain in residential school, far from home.

“The back story is when my father was in residential school and his mother died, they didn’t tell him until the following summer when they were sent home for the summer,” said Candace. “Any dysfunction that we have in our family, I can circle back to not just residential school, but to the fact that she died while he was there. And those who told me about it, the story is she died of a broken heart.”

At age 17, George was finally allowed to leave residential school, and quickly defied orders to remain on the reserve and made his way to Winnipeg to go to trade school. George soon began his career in service industry, met his wife and returned to Kahkewistahaw to build the home he would live in for the rest of his life. While he never shared his experiences with his children, his years in residential school continued to haunt him.

“It was my parents’ dream to move back to the reserve and my dad built the house, but his drinking increased and things fell apart and my parents split up,” said Candace. “I think being back in the community that he was taken from as a young child, his parents now gone, it just speaks to the fact that his whole life he was chasing regaining his identity. Those schools were designed to destroy your identity, your spirituality. All of that was stripped from him. But he hid it from us.”

Candace remained with her father, growing up in a home on reserve without heat or running water (“You learn how to melt snow for water,” she said), and at times very little food in the house. When Candace was 12 years old, her mother moved to Saskatoon and trained in USask’s Indian Teacher Education Program and went on to have a long successful career of teaching in the north, after coming to campus decades before Candace would arrive.

Growing up with a residential school survivor, there were many difficult days in Kahkewistahaw as Candace’s father bottled up the emotions of dealing with the demons from his past. But Candace also fondly remembers good days, too, of Saturdays spent walking with her father along the traditional trails along the ridge of the Qu’Appelle River Valley, a path she would walk years later on her own road to truth and reconciliation.

“Outwardly, he was still a very positive man, the funniest guy you would ever meet,” she said. “I get my work ethic, my hope and my passion for life from him. Before my father died, he said to me, ‘I don’t worry about my grandchildren, because my grandchildren have good parents.’ That inspired me to make sure that my children were always connected to their identity and their culture with pride, and that made me want to learn more.”

This past summer, Candace had that opportunity to learn more about the place that changed everything for her father. Inspired by national Poet Laureate and Elder Louise Bernice Halfe – Sky Dancer, she took part in the annual 100-mile 10-day walk organized by the Saskatchewan Historical and Folklore Society. This year’s walk traced traditional trails through the Qu’Appelle River Valley system that she knew so well from her journeys with her father as a child, through her home in Kahkewistahaw, and her grandmother’s community in Cowessess First Nation.

Cowessess was the site of the recent discovery of 751 unmarked graves at the cemetery near the former Marieval Indian Residential School. It is also where Candace’s grandmother is buried.

“All my life I’ve wondered about my grandmother, because my father was only eight years old when she died,” said Candace. “I went to the Cowessess site, which is only about four miles from my house, and I sat there and I know she is there, under the ground with those children. She was never a grandma to me, but she was a grandma to all these children and that gave me such a sense of closure and comfort that her life meant something.”

According to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, 18 children are also confirmed to have died at the Birtle school where her father attended. However, a recent academic report concluded that more unmarked graves are likely located on the site. Little did Candace know that she would have a chance to visit that site during her walk back in time.

This year’s 10-day journey began across the border in Manitoba in the largely Métis community of St. Lazare, where by chance Candace met USask Michif advisor Elder Norman Fleury’s nephew, who was able to take her the Birtle school site that haunted her father for the rest of his life. Located on what is now private property, with owners who shun visitors, Fleury’s nephew helped secure a brief on-site visit for Candace, on a day that she will never forget.

“We arrived at the back of the building, where the bricks have fallen and windows have been smashed out and it is really decrepit and haunting,” said Candace. “And I found myself standing there in front of this place and looking at all the busted windows and I can almost see children in the windows and I can imagine my father being there. Everything that has transcended from that time in my family, with my siblings, my parents’ marriage, I can centre back to here. And now, here I was standing in front of Birtle Residential School wondering how did he survive here?

“I am not a very good singer, but I wanted to sing for him. I wanted to show him that identity can be reclaimed, that language can be reclaimed, that spirituality can be reclaimed. So I smudged and I prayed and I drummed, and I asked to be heard. I wanted him to hear me, and eventually the song came out of me.”

The moment proved to be both painful and cleansing for Candace, and ultimately provided a sense of hope for the future that her father was denied.

“There were so many moments where I felt that he was there with me,” she said. “I felt I could give my father a sense of peace that I am living the life that he was denied, here in this space where he was held captive, and that there is hope for the future because even in a dark place like that, culture can return. I felt enlightened and I felt unburdened.”

Passing by the gardens that her father was forced to tend during the 12 years he was forced to spend in Birtle, Candace reached down and dug into the ground to pull out a large rock that she carried for the rest of the journey home.

“I put down some tobacco and I thanked the Creator for hearing me and as we started walking out of the area, I wanted a keepsake, something that was likely there when he was there,” she said. “So I stepped off the path and dug my hand deep into the ground and I pulled out a rock and I put it in my pocket. We believe in our culture that everything has a spirit and the rocks are our grandfathers, the rocks hold the stories and they are alive. I felt empowered as I experienced walking away from the residential school, and with every step, I felt he was with me. I felt like I brought him home.”

After he returned to Kahkewistahaw, Candace’s father rarely left home, joining her just once on campus at the University of Saskatchewan where Candace has made her home for the past 20 years.

“He came to campus once back in 2007 during Congress and all the teepees were in The Bowl, and he was enamoured by the place, and he said, ‘You work here?’ And I said, ‘Dad, this is my community’, and he was so proud, so proud. I don’t think he really imagined what my life was like here.”

In so many ways, Candace is living the life that her father always wanted for her; proud of her past, her culture, her traditions, and making a difference on campus in helping Indigenous students, staff and faculty feel at home, too.

As the country prepares to remember the victims of the residential school system and honour the survivors and their families on Sept. 30 during the first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, Candace’s thoughts are once again with her father, who passed away 10 years ago.

“I have such respect for his experience and I think I have an even deeper respect for the man he was, in spite of where he was,” she said. “I can’t imagine the level of strength it must have taken him — after what he experienced — to raise me with hopes and dreams and belief in myself, and with no shame. He wanted that for other people. He wanted that for us. He never shared his story, but I believe he would be proud because I am re-telling the story from a place of hope.”