Diagnosing concussion could be as easy as a blood test

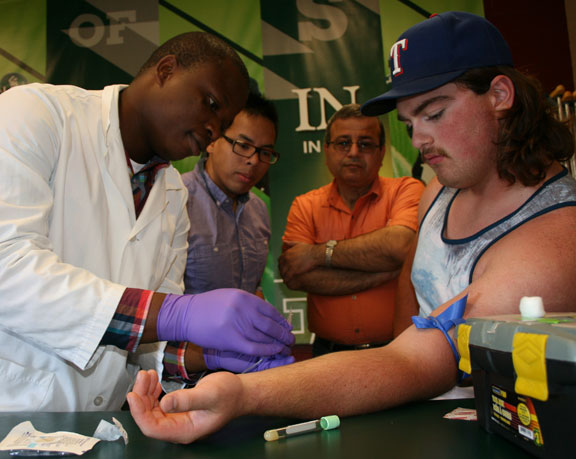

Huskies football defensive lineman Caleb Eidsvik takes up a lot of room as he sits on an examining table in the Huskies trainer’s room at Griffiths Field, patiently waiting for pharmacology student Hungbo Qudus to draw a small sample of his blood.

By Michael Robin At six-foot three and 260 pounds, Eidsvik exudes strength and good health. And that's the problem, according to researcher Changiz Taghibiglou, since Eidsvik is suspected of having a concussion.

At six-foot three and 260 pounds, Eidsvik exudes strength and good health. And that's the problem, according to researcher Changiz Taghibiglou, since Eidsvik is suspected of having a concussion.

"There's no easy way to conclusively diagnose concussion now. You need an MRI or a CT scan," he said. "Whether it's car accidents, falls or sports injuries, we actually don't have any simple tests."

Taghibiglou is an assistant professor in the College of Medicine's Department of Pharmacology. If he gets his way, testing for concussion will be so simple that a test kit will be a standard item in every medical bag, to be used by trainers and coaches at football fields and hockey arenas, and even by first responders and EMTs.

Diagnosis of concussion is critical. While short term symptoms such as vomiting, confusion and headache may be easy to spot, Taghibiglou explained that long-term effects can be more subtle and easier to brush off. This can be extremely dangerous: if the person suffers a second concussion before fully recovering from the first, they are at high risk of developing permanent brain damage, psychiatric problems or even dying. There are also risks of long term effects, including Parkinson's and Alzheimer diseases, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

At the heart of Taghibiglou's concussion test is a molecule that exists on the surface of brain cells. Through research carried out with scientists at the Canadian Department of National Defence, a link was found between the molecule and brain trauma. This research is ongoing and represents one of the agency's many inquiries into the effects of battlefield blasts on soldiers.

"Physical injuries are easy to spot but with a concussion a person can appear fine," Taghibiglou said. "In the worst case, there are no outward signs of injury so they are sent back out, re-injured, and suffer significant neurological issues later."

Taghibiglou explains that head trauma – whether from an accidental blow to the head, a hard slam on the gridiron or a forceful check against the boards – can knock certain brain cell molecules loose. Once free, they circulate in the blood where they can be detected by a simple blood test (a patent for the test has been applied for through the U of S Industry Liaison Office).

Working with Huskie Athletics, Taghibiglou, Qudus and graduate student Nathan Pham are gathering blood samples from athletes pre- and post-injury. Taghibiglou praised Director of Huskie Athletics Basil Hughton and Huskies Head Therapist Rhonda Shishkin for arranging access, particularly during peak season.

"We're collecting from the football team and are also looking for concussion in other teams such as soccer and hockey," he said.

Since the test is so new, the research team also needs about 300 male and female volunteers to donate small blood samples to establish the normal level of the concussion-associated molecules in the blood.

"There are no values in the reference books, simply because no one has gathered the data yet. Our ultimate goal is a simple diagnostic test, much like the blood sugar tests used by diabetics." The test would be particularly valuable for rural and remote communities that lack the medical equipment typically used for trauma diagnosis.

"Small health clinics don't have an MRI. It may help rural doctors refer their patients to larger centres and know what's going on."

Taghibiglou said anyone contributing to the project monetarily or with a small blood sample can contact Pham at 306-966-2552 or nathan.pham@usask.ca.