Get smart

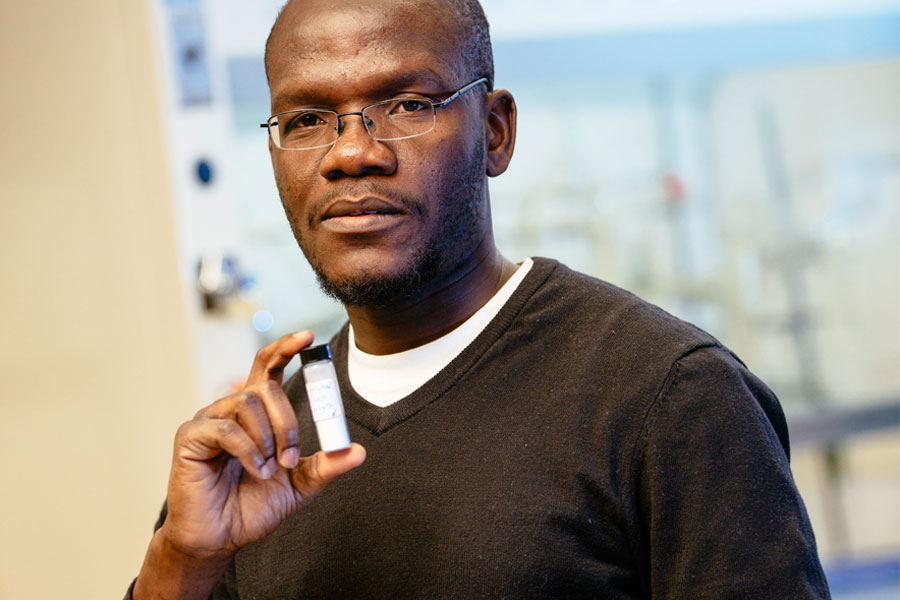

A University of Saskatchewan chemistry student has developed a new “smart material” with potential to significantly improve ways of combatting toxic waterborne contaminants that threaten our health and environment.

By University Communications Smart materials have properties that change in response to their environment. An example is shrink-wrap which when cooled is a clear film and when heated can tightly wrap around an object such as meat or electrical products.

Smart materials have properties that change in response to their environment. An example is shrink-wrap which when cooled is a clear film and when heated can tightly wrap around an object such as meat or electrical products."Smart materials have potential use in a wide range of applications such as the ability to trap POPs in aquatic environments," said Abdalla Karoyo, a research assistant who recently completed his PhD.

POPs—short for "persistent organic pollutants"—include some pesticides (such as DDT), industrial chemicals (such as PCBs), and unintentional by-products of industrial processes (such as dioxins).

Because these toxic chemicals can remain for a long time in the environment, they slowly accumulate in living organisms through the food chain, causing health risks such as cancer and even death in very high concentrations.

The smart material Karoyo has developed is a chemically modified starch that reversibly extends or contracts like a miniature molecular accordion when heated at certain temperatures or placed in contact with contaminants in water.

In lab research, Karoyo was able to use the material to "catch" and "release" pollutants in the environment in a controlled way. He showed that the novel material could trap significant amounts of concentrated POPs at a level exceeding that of commercially available materials.

"Abdalla's keen eye for detail and meticulous experimental skills allowed us to unravel the remarkable and unique behavior of this novel material," said professor Lee Wilson, Karoyo's supervisor.

The capability of this new smart material to remove pollutants such as textile dyes and petrochemicals from aquatic environments could be significant, he said.

Wilson and a Canadian company are currently conducting further research and development with the hope of commercializing the technology for a wide range of water treatment technologies. Karoyo will be part of the commercial development if the work becomes patented and licensed.

Due to its unique properties, the new material not only holds promise for environmental remediation but also for developing novel chemical sensors, biomedical implants, and drug delivery devices, he added.

Karoyo said the material is unique because it can be re-used several times to capture pollutants.

"You can use the smart material to catch toxic chemicals in the water, release them somewhere else, recycle, and use it again," he said. "And since it is a starch, it is biodegradable and can be safely disposed of once used."

Because starch-based biopolymers are very cheap, the smart material may also be cost-effective to produce on a large scale.

Karoyo's commitment to the project is deeply felt. Originally from Kenya, he is well aware of the disruptive effects of contamination on Lake Victoria, the world's largest tropical lake, where pollution is blamed for the death of the majority of fish species. POPs have been found in the lake's sediments.

"For me water is sacred. Everything is attached to water and without water there is no life," he said. "I wanted to do something which benefits not just me but also the global community."

Article written by Federica Giannelli, a graduate student intern in the U of S research profile and impact unit. This article first ran as part of the 2014 Young Innovators series, an initiative of the U of S Research Profile office in partnership with the Saskatoon StarPhoenix.