“Bat Men” shed light on bat super immunity

University of Saskatchewan (U of S) researchers may have unlocked the secret behind bat “super immunity” to deadly respiratory diseases such as SARS.

By Federica GiannelliCoronaviruses such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle-East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) cause serious and often fatal disease in people, but bats seem unharmed.

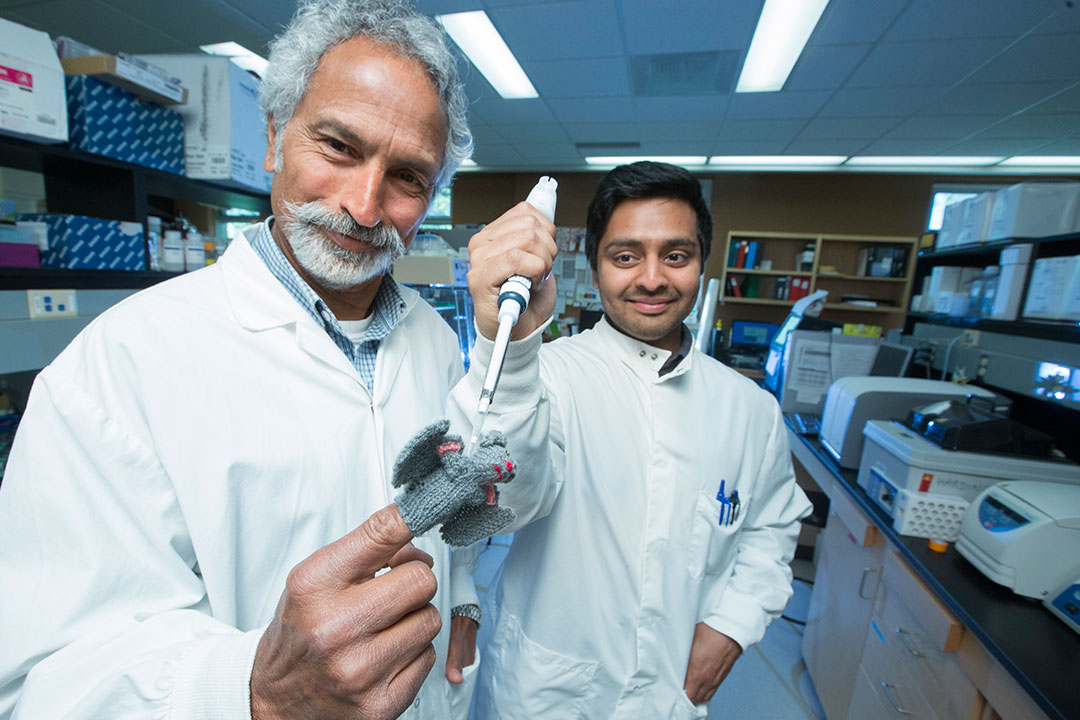

Veterinary microbiology PhD candidate Arinjay Banerjee and his professor Vikram Misra have now found some clues.

In an article published this week in Nature’s Scientific Reports, they conclude that unlike with human cells, bat cells actively suppress inflammation when they are infected with viruses.

“This knowledge might lead to new therapies for slowing down disease progression in humans and might even reduce death rates in the future,” said Misra, but he cautions further research is needed.

Not much is known about bat “super immunity,” said Banerjee. “We are among only a few groups worldwide working to decipher it.”

In 2003, a SARS outbreak in Toronto, which had originated in Asia, caused more than 40 deaths in Canada and 400 infections. Banerjee explains SARS and MERS are deadly to humans because they cause extensive lung inflammation leading to severe tissue damage. Both viruses are thought to have spilled over from bats to people and other animals.

“In people these diseases work in a way that’s like revving your car at very high rpms for a long time — you end up destroying the engine,” said Banerjee. “Bats seem to have evolved to suppress the revs, even when you floor the gas pedal.”

Dubbed the “Bat Men,” the team in Misra’s lab used cells from Prairie bats to develop the first commercially available cell line (a layer of cells that continuously replicate) ever developed for North American bats.

This cell line was tested by microbiology professor Yan Zhou at U of S VIDO-InterVac and by researcher Vincent Munster at U.S. National Institutes for Health laboratory in Montana. They found that the cell line can effectively grow coronaviruses such as SARS, MERS, Ebola and pig epidemic diarrhea viruses.

Misra and Banerjee injected the cell line with a synthetic molecule resembling a SARS bat coronavirus, and studied the bat cells’ immune response in comparison to human cells.

They found both types of cells activate anti-viral genes for combatting this infection. But unique to the bat immune system, a protein called c-Rel stops a key “inflammation-triggering” signal, whereas in humans severe inflammation causes tissue damage.

As a very ancient animal species, bats may have evolved with survival strategies for certain diseases, said Misra.

“We need a One Health approach—integrating the health of people, animals and the environment — to deal with problems such as emerging infectious diseases,” said Banerjee.

Now the “Bat Men” are working with microbiology professor Darryl Falzarano at VIDO-InterVac to test MERS infection on bat cells. They want to understand why the virus doesn’t “shut down” the bat immune responses as it does in humans.

This research is funded by the federal agency NSERC and the Saskatchewan Innovation and Opportunity Scholarship, and also involved U of S veterinary pathology professor Trent Bollinger and lab technician Noreen Rapin.

Federica Giannelli is a graduate student intern in the U of S research profile and impact unit.

This article first ran as part of the 2016 Young Innovators series, an initiative of the U of S Research Profile and Impact office in partnership with the Saskatoon StarPhoenix.