U of S researchers discover vampire bugs’ fatal flaw

University of Saskatchewan researchers have found a unique blood-cooling system in the head of “kissing bugs” that transmit life-threatening Chagas disease—a finding that may help develop next-generation pest control tools to thwart these blood-sucking critters.

By Federica Giannelli“These insects are developing resistance to insecticides, so we need to better understand their biology to find new ways for killing them and limit the spread of Chagas disease,” said U of S physiology professor Juan Ianowski.

Untreatable and often undetected, Chagas disease affects six to seven million people, mostly in Latin America where it spreads mainly through Rhodnius prolixus, known as the “kissing bug” for its habit of biting around its victim’s mouth.

Infected bugs deposit the Chagas disease parasites into a victim’s blood system when feeding. The human immune system cannot kill the parasites which keep mutating and cause severe heart problems that lead to death within 10 to 30 years.

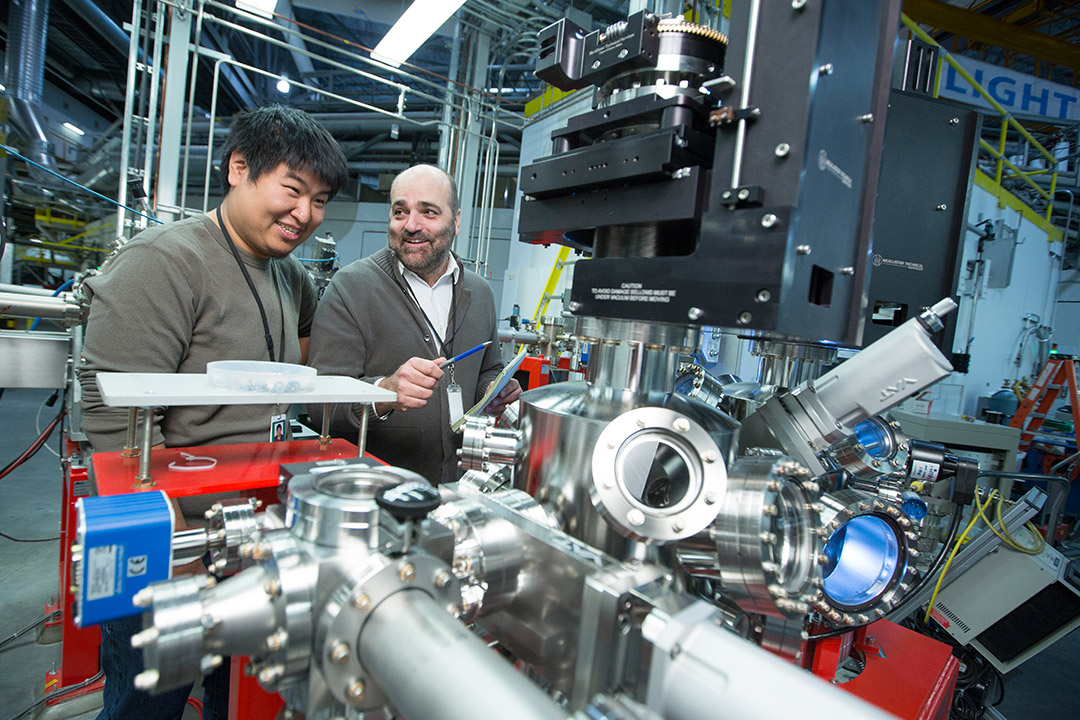

Ianowski and his PhD student Xiaojie Luan have been the first to provide evidence that the special circulation system in the vampire bug’s head prevents the heat of the incoming blood meal from harming the bug. Their findings, published last week in the journal eLife, may be used to develop chemicals that could disrupt the insects’ heat exchange system to kill the critters.

The research was done at the U of S Canadian Light Source (CLS) synchrotron in collaboration with researchers from France and Brazil.

“We needed very high imaging resolution and the CLS was the only place that had X-rays powerful enough to visualize how the blood moves from the insects’ mouths to their bodies,” said Luan, who developed a new imaging technique at the synchrotron to scan the live insects.

The researchers showed that meal blood and the insect’s blood, which are at different temperatures, flow in opposite directions and slowly exchange heat—the secret of the insect’s survival.

“We’ve seen similar mechanisms in the body of other insects, but this is the first time we found it in the head of an insect,” said Ianowski.

Luan, who moved from China to pursue his post-secondary education at the U of S, took images and shot videos of more than 50 insects feeding. He used insects that Ianowski grew in the lab, where thousands of them are kept in jars.

“My insects, of course, don’t have the Chagas disease parasites and are completely harmless,” said Ianowski.

“Some Latin American species can survive cold to an extent, so one day we may have them close to here,” said Ianowski. “That’s why it is crucial that we keep researching.”

With climate change, he said the Latin American insects are moving North, and some people in the U.S. who never went abroad have been infected. Immigration of infected people could also be a factor.

The U of S team was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), and were led by Claudio Lazzari, a researcher at the University of Tours in France.

Federica Giannelli is a graduate student intern in the U of S research profile and impact unit.

This article first ran as part of the 2017 Young Innovators series, an initiative of the U of S Research Profile and Impact office in partnership with the Saskatoon StarPhoenix.