Bad molars? The origins of wisdom teeth

Our grandparents and parents tell stories about the time when kids routinely had their tonsils removed. But for people born in the 1960s and later, their routine surgery stories are about having third molars, a.k.a. wisdom teeth, taken out.

By Julia BoughnerAs a scientist who studies the evolution and development of faces and teeth in humans and other animals, whenever I ask a room of people if they’ve had any wisdom teeth removed, the hands of at least half the audience shoot up.

People want to share their wisdom tooth stories as well as to ask: Why do we have wisdom teeth? Why do they get impacted? Why don’t we just evolve them away?

Humans are primates. Our species’ closest living cousins are African apes, specifically chimpanzees. Apes have wisdom teeth, so do monkeys. Having wisdom teeth is just part of our evolutionary legacy.

Evolved wisdom?

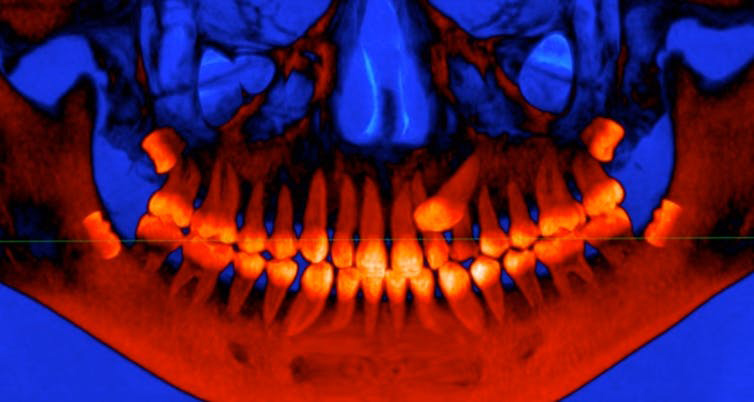

Just like the rest of your teeth, wisdom teeth form inside your jawbone. But they form very late compared to our other teeth.

Second molars start developing around age three. Wisdom teeth often don’t start growing until age nine, but they’re highly variable, starting as young as five and as old as 15. They erupt from the gum between ages 17 and 24, if not older.

A tooth that doesn’t properly emerge through your gums and into your mouth is “impacted.” Impacted teeth can be linked to problems includinggum disease, cysts or damage to the second molar.

Even when wisdom teeth start out badly angled, they can rotate and shift position in your 20s or 30s.

Wisdom teeth are not only the teeth most often impacted, but also the teeth that often fail to form at all.

Because wisdom teeth aren’t essential to modern human survival, people often ask whether evolution is weeding out this bothersome trait. But I don’t think so.

First, impacted wisdom teeth may cause us problems, but they rarely kill us. Even if they did, for evolution to select against wisdom teeth, impacted molars would have to cull us from the gene pool before we had kids. This would stop us from passing on any genes that might lead to impaction.

But it’s unlikely that specific “impaction genes” exist in the first place. There are, however, several risk factors for impaction, including what we eat.

Cramped quarters

The main reason we get impacted wisdom teeth is lack of space at the back of the jawbone. Our team found that when wisdom teeth develop and emerge very late, most of this space is already claimed by the first and second molars, so the wisdom tooth can’t move upwards and through the gums.

A related problem is jaw growth and overall length. If the jaw doesn’t grow long enough, fast enough, later-forming wisdom teeth also run out of space and can’t erupt properly, if at all.

But space isn’t the whole story. Scientists still can’t explain why some wisdom teeth become impacted. We need new ways to help dentists reliably predict which wisdom teeth are at risk.

Something to chew on

Based on what we do know, can we prevent impaction? Maybe.

Apes rarely have impacted wisdom teeth. The same holds true for humans who eat non-industrialized diets.

Our jaws evolved to expect biomechanical stimulation from a diet of, say, nuts, uncooked veggies and raw meats. These days, we tend to feed our jaws soft, processed foods, like smooth peanut butter on squishy bread. As a result, for the past few decades, we’ve probably not been maxing out the growth potential of our jawbones.

If you’re still growing, you can act now. Start eating crunchier, chewier foods, such as nuts and raw vegetables. And if you have kids, encourage them to eat jaw-moving foods as early as it’s healthy to do so. While science can’t yet say for sure that it will work, it probably can’t hurt.

A public health problem?

Millions of wisdom tooth extraction surgeries are performed worldwide each year. The treatment rate for wisdom tooth problems is higher than the rate of impaction itself. Up to one-third of these surgeries are needless.

Extraction surgery carries its own risks, too, including injury to nearby teeth, nerves, jawbone or sinuses. That’s a big waste of time, energy, money, avoidable pain and risk. Shunning non-essential surgery is why we no longer routinely send kids for tonsillectomies.

Healthy, erupted wisdom teeth aren’t usually a big problem for most people. They may have to brush these hard-to-reach teeth extra carefully to avoid decay.

Some impacted wisdom teeth don’t pose risk. But others can damage the second molar and surrounding jawbone, or cause infection and pain. These molars probably will need to come out.

When should you get them taken out? Some surgeons prefer to remove wisdom teeth early, at age 16 or 17, even though these molars may still rotate and emerge properly. On the other hand, removing molars late in life can be harsh on elderly, fragile or ill patients.

Watchful waiting may be a reasonable approach, and one advocated byseveral federal and public health agencies, as well as dentists.

Wisdom teeth are not necessarily essential but they’re not useless, either. They’re tools for eating, a part of our bodies, and a fascinating case study of how the evolution of human culture and diet can impact human development and growth.

is an Associate Professor, Evolutionary Developmental Anthropology at the University of Saskatchewan.