U of S launches device into near-space to track climate change

The satellite device could help work will help scientists understand how aerosols work and how they affect climate.

By Federica GiannelliWorking with the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), a University of Saskatchewan research team has just launched a novel device into the edge of space to study the cooling effects of aerosol particles on a warming climate.

The launch of the particle-imaging device early Sunday at the CSA’s Timmins, Ont., base is part of the agency’s STRATOS program, which gives universities and industry the opportunity to test devices in the high atmosphere at 35 kilometers above Earth using special balloons larger than a football field.

“This will be a testing demonstration of the technology, to see whether it works in space,” said Adam Bourassa, physics and engineering physics professor in the College of Arts and Science. “If all goes well, we may aim to send it to space on a real satellite in three or four years from now and get new aerosol measurements within the next five years.”

Aerosols are a hot topic in the scientific community for their cooling effect that counteracts global warming caused by greenhouse gases. Aerosols, fine, solid particles or liquid droplets suspended in the air or in a gas, are swept into the upper atmosphere from volcanic eruptions, pollution and desert sands, and look like haze in the sky on a bright day.

“This will be a testing demonstration of the technology, to see whether it works in space,” said Adam Bourassa, physics and engineering physics professor in the College of Arts and Science. “If all goes well, we may aim to send it to space on a real satellite in three or four years from now and get new aerosol measurements within the next five years.”

Aerosols are a hot topic in the scientific community for their cooling effect that counteracts global warming caused by greenhouse gases. Aerosols, fine, solid particles or liquid droplets suspended in the air or in a gas, are swept into the upper atmosphere from volcanic eruptions, pollution and desert sands, and look like haze in the sky on a bright day.

“Our work will help scientists understand how aerosols work and how they affect climate, and maybe someday help meteorologists predict weather more accurately,” said Bourassa, who is a member of the U of S Institute of Space and Atmospheric Studies, the largest and most comprehensive institute of its kind in Canada.

When dense enough, aerosols act as a shield that reflects the sun’s rays back from Earth. In 1991, a massive eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines shot enough aerosols in the atmosphere to lower Earth’s temperature by half a degree Celsius for almost two years.

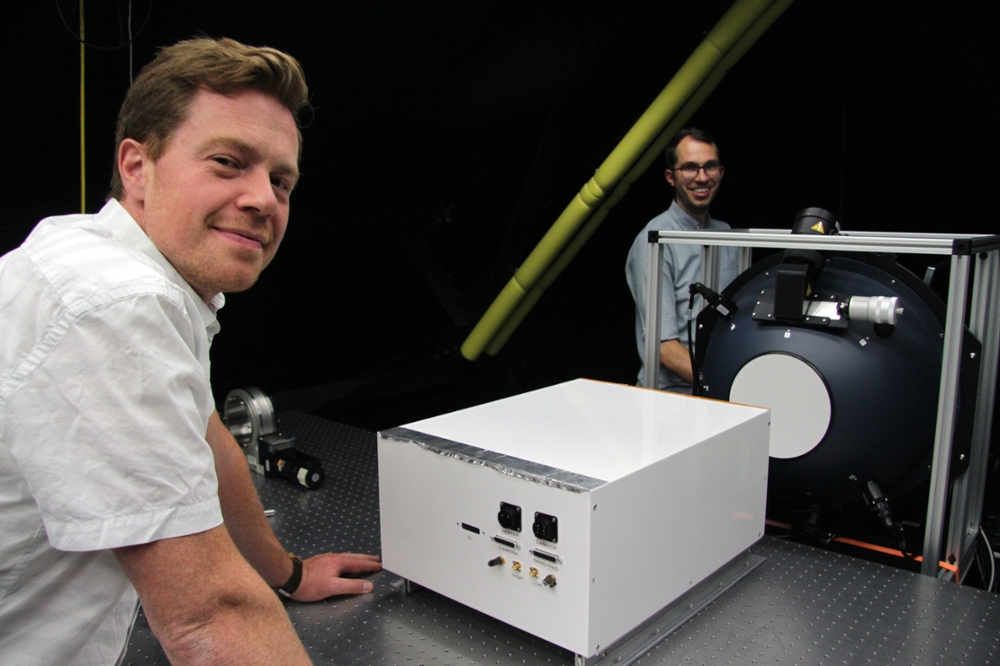

But it is unclear how the particles operate in the atmosphere. Bourassa and his PhD student Matt Kozun have been working on the technology that can solve this scientific unknown.

“Our device will give a better idea of the composition and distribution of aerosols, and determine how much aerosol comes from volcanic eruptions and how they affect cloud formation,” said Kozun.

Kozun has improved the design of a high-resolution imaging device called ALI (Aerosol Limb Imager) that can help study aerosols in the stratosphere, the upper part of the atmosphere. Bourassa’s research group has been developing the device at the U of S since 2013.

“The device is now smaller, almost the perfect size to be installed on a satellite,” said Kozun. “My team has improved the electronic control system, so that power failures are much less likely at the minus 50 degree Celsius temperatures of the stratosphere.”

The improved device is able to take high-resolution images of aerosols by using radiofrequency waves to vibrate crystals made of a silicon-like material called tellurium dioxide inside ALI.

The new ALI is also more efficient because it is able to distinguish aerosols from clouds, which are a mass of condensed water vapour floating in the atmosphere. The device has been developed in collaboration with technology company Honeywell Aerospace, and funding from the Canadian Space Agency.

Though Bourassa acknowledges the cooling benefits of aerosols, he disagrees with scientists who suggest injecting more aerosols into the atmosphere to solve climate change.

“The idea that we can keep polluting the globe because aerosols shield the atmosphere is simply unthinkable,” he said. “What goes up always comes down, so injecting more aerosols in the atmosphere is dangerous.”

Federica Giannelli is a graduate student intern in the University of Saskatchewan research profile and impact unit.

This article first ran as part of the 2018 Young Innovators series, an initiative of the U of S Research Profile and Impact office in partnership with the Saskatoon StarPhoenix.

Article re-posted on .

View original article.