Researchers provide new insights into fate of Franklin Expedition

Synchrotron studies of bone and teeth have led a multi-institution team of scientists to conclude that lead poisoning did not play a pivotal role in the deaths of crew members of the ill-fated Franklin Expedition of 1845, says a paper published today in the journal PLOS ONE.

“Our findings don’t mean the crew members weren’t exposed to high levels of lead, and they don’t mean the sailors weren’t impacted. But our findings don’t lend support to massive and sustained lead poisoning that would have compromised them any more than any sailor of that era would have been compromised,” said David Cooper of the University of Saskatchewan, an author of the paper.

Data collected by the team don’t support the theory that compromised physical and/or neurological health resulting from lead poisoning prompted the stranded sailors’ fatal march southward in April 1848 to try to reach a Hudson Bay Company post, said Cooper, Canada Research Chair in Synchrotron Bone Imaging in the Department of Anatomy, Physiology and Pharmacology at the U of S College of Medicine,

That theory arose from previous analyses of bone, hair and soft tissue samples from the frozen bodies of the sailors, which had found they had high levels of lead in their tissue.

The 11-member team includes Treena Swanston, who was a post-doctoral fellow on Cooper’s team at the U of S when the research began and is currently an assistant professor at MacEwan University. She is lead author of the paper.

Team members investigated three hypotheses before reaching their conclusion, which is bound to add fuel to public and academic discussions that have been simmering since the discovery of the wrecks of the Franklin expedition ships, HMS Terror in 2016 and HMS Erebus in 2014:

● If elevated lead levels were experienced by crew members during the expedition, those who survived longer (their bodies were found on King William Island in the Arctic) would have more extensively distributed lead in their bones than those who died earlier on Beechey Island, where they spent the first winter.

● There would be elevated levels of lead in skeletal tissues formed near the time of death of sailors than in older tissue.

● If lead exposure played a key role in the failure of the expedition, the bone samples of the Franklin crew would show more extensive absorption of lead than the bones of British sailors of the same period who are buried in the Royal Navy cemetery in Antigua, West Indies.

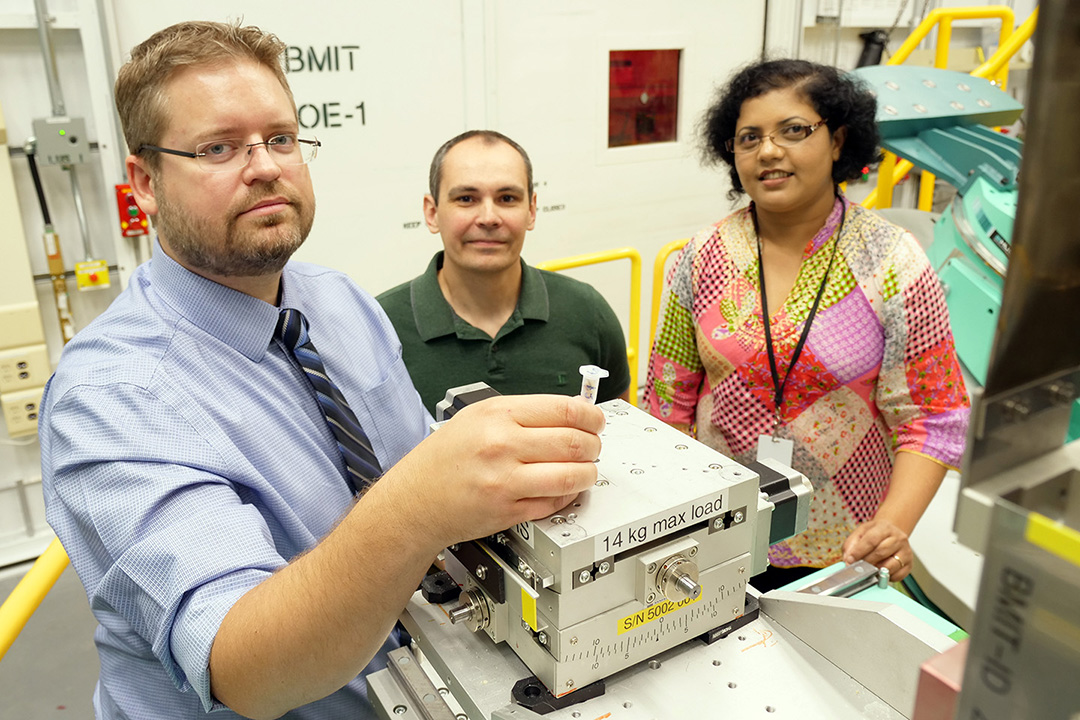

Cooper said data were gathered using the Advanced Photon Source (APS) in Illinois, thanks to the partnership between APS and the Canadian Light Source synchrotron, which belongs to the U of S. The data showed that bones gathered at the Arctic sites of Beechey and King William islands contained similar extensive distributions of lead, implying exposure long before the expedition.

While there was some evidence of lead exposure close to the sailors’ death, there was no consistent evidence of a marked elevation. Finally, the comparative analysis with the Antigua samples didn’t support the hypothesis that the lead distribution within the Franklin sailors was unusual for the time period.

“Taken altogether, our microstructural results do not support the conclusion that lead played a pivotal role in the loss of Franklin and his crew,” says the paper.

The research project was a team effort, Cooper said.

The project got its start when Cooper arrived at the U of S in 2007 and began doing research at the CLS, collecting data on the distribution of elements in bone. He reconnected with former graduate school colleague Tamara Varney, who was at Lakehead University researching British naval sites in the Caribbean.

Varney was wondering if rum-related lead poisoning had affected the sailors. She and Cooper partnered with Ian Coulthard, a senior scientist at CLS. Swanston joined Cooper’s team as a post-doctoral fellow and the group expanded from there.

“So we had an interdisciplinary group of scientists interested in the question of lead poisoning in the historical past, expertise and analytical technology available through the CLS, and a community of researchers in Canada that had access to remains from the Franklin expedition. This was a great partnership which highlights the benefits of collaborative research in Canada focused around the CLS,” said Cooper.

The team members are: Swanston, Cooper, Coulthard, Varney, Sanjukta Choudhury (U of S), Brian Bewer (CLS), Anne Keenleyside (Trent University), Madalena Kozachuk, Ronald Martin and Andrew Nelson (Western University), Douglas Stenton (University of Waterloo).

The research was funded through Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council grants led by Varney, Cooper’s Canada Research Chair, and Swanston’s CIHR Training Grant in Health Research Using Synchrotron Techniques (CIHR-THRUST) when she was at the U of S.

PLOS ONE paper: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0202983