The accidental discovery of stem cells

Unexpected results can happen at any level of research, says James Till, and “it’s how they’re dealt with that matters.”

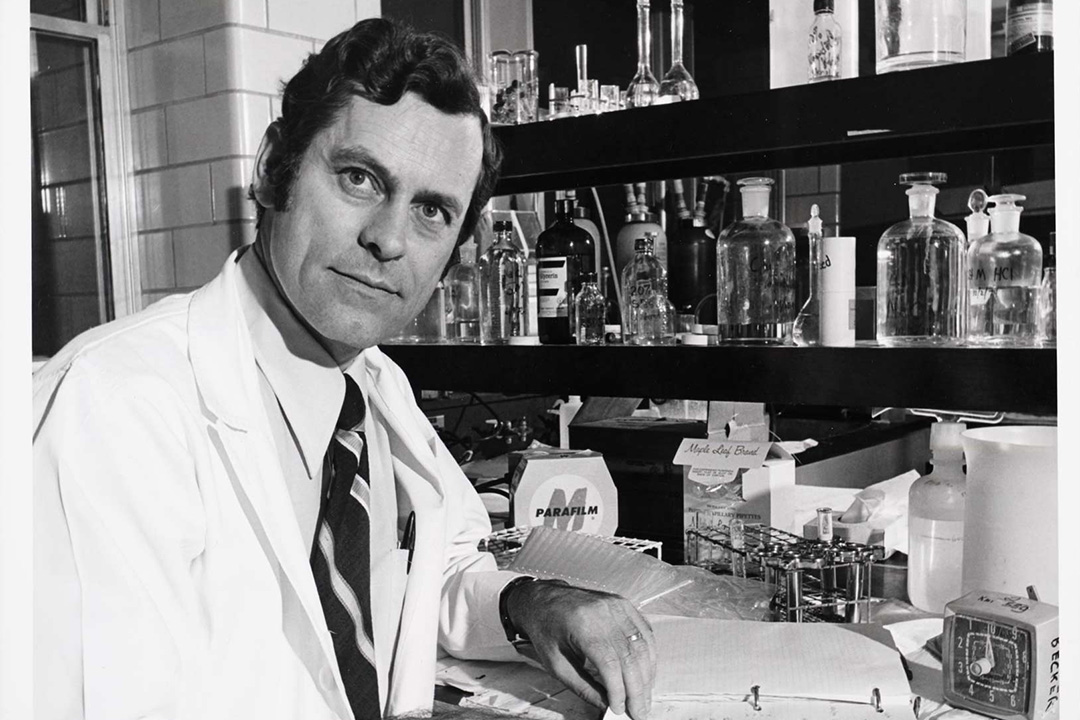

By Colleen MacPhersonTill knows of what he speaks; it was almost 60 years ago that the renowned University of Saskatchewan graduate, along with a colleague, found something unexpected in research results that simply could not be ignored.

Although they did not know it at the time, the two scientists were on the path to discovering stem cells and the great potential they hold for treating everything from blindness to spinal cord injuries.

The discovery was not a eureka moment, Till says, “but our reactions were the same. We both thought, ‘That’s really interesting.’ ”

Till was a researcher at the Ontario Cancer Institute in 1960 when he and his colleague, Ernest McCulloch, spotted an anomaly during a study they were conducting into the effects of radiation on mice.

The mice were irradiated with enough X-rays to kill them within 30 days if they did not receive a transplant of bone marrow cells. The mice were also injected with a varying number of cells in order for the researchers to determine how many cells it would take to keep the animals alive.

On a Sunday morning, several days after injecting the cells, McCulloch examined samples taken from the mice. The hematologist noticed small lumps on the spleens of the mice, one lump for every 10,000 injected bone marrow cells.

“Dr. McCulloch’s observation that the number of clumps, which we both thought of as colonies, was linearly related to the number of transplanted marrow cells suggested that the colonies might be clones—that they derived from single cells,” says Till.

“We weren’t sure what track we were on, but we quickly agreed on what we would do next. We needed more evidence that the colonies were clones.”

Till and McCulloch published their initial observation in 1961 in the journal Radiation Research to little fanfare, and then dedicated themselves to confirming their suspicion. Their work was also aided by graduate student Andy Becker and senior scientist Lou Siminovitch, with Becker’s experiments demonstrating “quite convincingly that the colonies were clones,” says Till.

Those results were published in Nature in 1963.

At the same time, Siminovitch, a molecular biologist and Till’s mentor for his postdoctoral work, was the lead investigator for studies “that revealed the cells that gave rise to colonies had, among their descendants, cells that could themselves give rise to new colonies. So, colony-forming cells could self-renew.”

Siminovitch’s work, also published in 1963, combined with the previous findings, “convinced us that we had blood-forming stem cells. Before then, we only referred to them as colony-forming units—CFUs—because we weren’t sure what we were dealing with.”

That ability to self-renew, says Till, “seemed to us to be one crucial defining property of stem cells,” and it is the definition of stem cells that is still in use today.

“It took us three years to establish that we were, indeed, dealing with something of considerable significance,” he says.

Till and McCulloch’s work formed the basis for all stem cell research going on today, and paved the way for advances such as bone marrow transplants to treat cancer. It also opened the door to the field of regenerative medicine—in which scientists seek ways to regrow, repair or replace damaged or diseased cells, use therapeutic stem cells and even produce artificial organs.