The hidden history of Indigenous stereotypes in tabletop games

Tabletop games have entertained and even educated people for over a century. While games today often sanitize conquest in North America rather than glorify it, they continue to grapple with the same questions about race, culture and history that game-makers 100 years ago encountered.

By Benjamin HoyDespite the increased popularity of video games, tabletop games are still thriving. The game and puzzle industry in the United States now exceeds $2 billion in annual sales. Dozens of board game cafés, including the wildly popular Snakes and Lattes in Toronto, dot North America’s urban centres.

Board games even have their own holiday. On April 28, thousands of board and card game players from around the world will celebrate International Tabletop Day. It’s marked by charitable events, live-streamed broadcasts and, best of all, gaming.

Reinforcing stereotypes

Looking only at the industry today, however, conceals a past that has contributed to the ways that stereotypes are passed between generations.

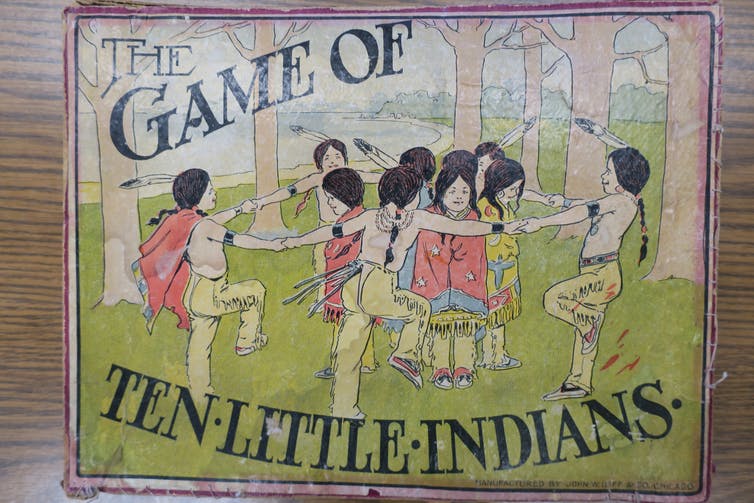

In the 19th century, board game companies in the United States and Europe realized the potential of using Indigenous imagery to sell their merchandise to boys in particular. These early game-makers depicted Indigenous people as savage enemies or peaceful children. They borrowed these stereotypes from Wild West shows and dime novels.

Indigenous imagery offered more than a marketing opportunity. It also offered a way to teach American children about their history and culture. The games introduced complex ideas like territorial annexation and assimilation while players were still too young to fully understand these ideas.

The Game of United States History (circa 1903), for example, depicted the pre-contact residents of North America as “roving tribes of warlike Indians.” It contrasted these pre-contact depictions with Indigenous Americans who attended residential schools, wore European clothing and embraced “civilized occupations.”

Games obscure difficult histories

These rosy before-and-after depictions left the horrors of the schools untouched and implicitly told children that American expansion had been honourable and for the benefit of Indigenous people.

Tabletop games slowly changed the ways they depicted Indigenous communities in the aftermath of the Second World War. The increased importance of advertising encouraged board game companies to rely on well-known brands, like the Lone Ranger and Tonto, instead of developing new ones.

The emerging Indigenous civil rights movement — such as the Indians of All Tribes’ occupation of Alcatraz in 1969-71 and the American Indian Movement’s occupation of Wounded Knee in 1973 — was also difficult for the industry to ignore.

Resistant to change

Despite these pressures, game companies remained resistant to change throughout the 1970s and 1980s. In August 1973, a leading trade magazine for the American toy industry noted that while the industry reflected a wider variety of life experiences, there had been little engagement with Indigenous communities “probably because such markets are not considered large enough to be worth the trouble.”

In the long run, the Civil Rights Movement changed what the American public was willing to buy. Caricatures certainly remain, but financial pressures splintered the way game-makers depicted Indigenous people.

Many modern companies have moved towards sanitizing an often violent and difficult past to make it accessible to a young audience. That approach has created as many new problems as it’s solved. The best companies have developed products that are capable of retaining the complexity of the past, while making them accessible.

History, unfortunately, is complicated and unflattering. For game designers who are asked to represent identities and histories with bits of wood, plastic and cardboard, the task is certainly a challenging one — one they have been grappling with for more than 100 years.