USask team sheds light on new Alzheimer’s drugs

A University of Saskatchewan (USask) research team has shed light on the functioning of potential new Alzheimer’s disease drugs that target copper plaques in the diseased brain, a finding that could help improve the drugs to benefit patients’ learning skills and memory.

By Federica GiannelliMetals such as copper, zinc and iron are present naturally in our bodies. When correctly produced and regulated by proteins in brain cells, copper is vital for neuron survival and communication. But in the Alzheimer’s disease brain, toxic levels of copper and other metals accumulate in plaques, which are misfolded protein deposits in the brain. This toxicity is linked to degeneration of patients’ mental skills.

New in-development drugs specifically target copper in the plaques to break them down, removing the metal. But how this works is not well understood.

“Much of the emphasis to date by other scientists has been on disassembly and dispersal of the plaques, but so far no treatment has achieved this and the consequence of dispersal may be to seed more plaques,” said USask chemistry PhD student Kelly Summers.

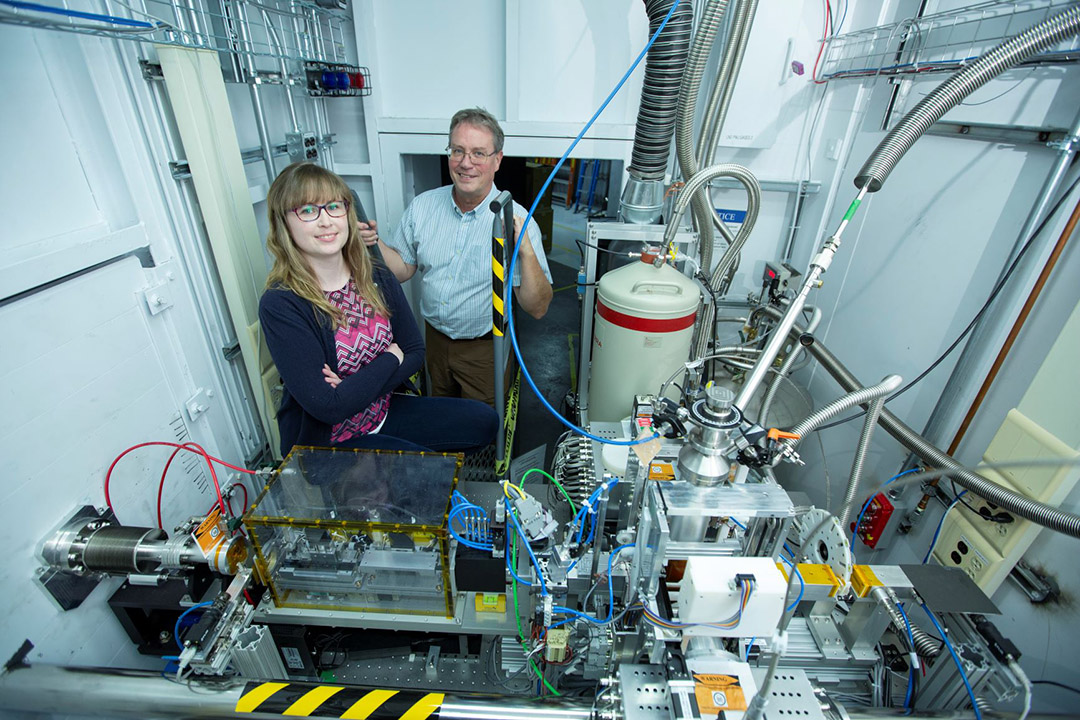

Using synchrotron facilities around the world including the USask Canadian Light Source, Summers has found for the first time that instead of removing the copper, the new drugs isolate it, binding to it like molecular clamps.

“Our findings suggest that we need to re-think drug design for Alzheimer’s treatment, and that a better and more realistic treatment may be to mitigate the toxic effects from bound metals, which may be what these new drugs do,” said USask geological sciences professor Graham George, Summers’ supervisor along with geological sciences professor Ingrid Pickering and chemistry professor Stephen Urquhart.

George noted that the combination of synchrotron methods has provided insights that would be impossible to obtain from any other methods. The team’s results are published in Inorganic Chemistry.

“Our findings could help further improve the new drugs to better target the copper build-up in patients’ brains,” said Summers. “Researchers could influence how fast the drugs work and even small tweaks could go a long way in changing the way the drugs could help slow down or potentially stop the disease.”

The next step for the USask researchers will be to extend the study to other groups of drugs currently being tested.

Alzheimer’s disease is untreatable and the leading cause of dementia. The Alzheimer Society of Saskatchewan estimates that nearly 20,000 people live with dementia in the province today, projecting that over the next three decades this number should rise substantially along with an increase to almost $40 billion in healthcare costs.

While the new copper-binding drugs on the horizon are promising, scientists developing them will have to test them further for dosage and potential side effects before they can be considered safe for human use.

An international chemistry organization has recognized Summers as one of 118 outstanding young chemists around the world.

“When I first began this research I did not expect so many people to have been touched by Alzheimer’s, but almost every time I talk about my work I discover someone with a family member or friend suffering from it. For me, it reaffirms the importance of this kind of research,” said Summers.

The research is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), the Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation (SHRF), and Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI).

Federica Giannelli is a graduate student intern in the University of Saskatchewan research profile and impact unit. This content runs through a partnership with The StarPhoenix.