Drug-resistant superbugs a growing concern

It doesn’t garner the same mass media attention as the global health emergency of the ongoing coronavirus outbreak, but there is another world health threat looming that researchers have been warning of for decades.

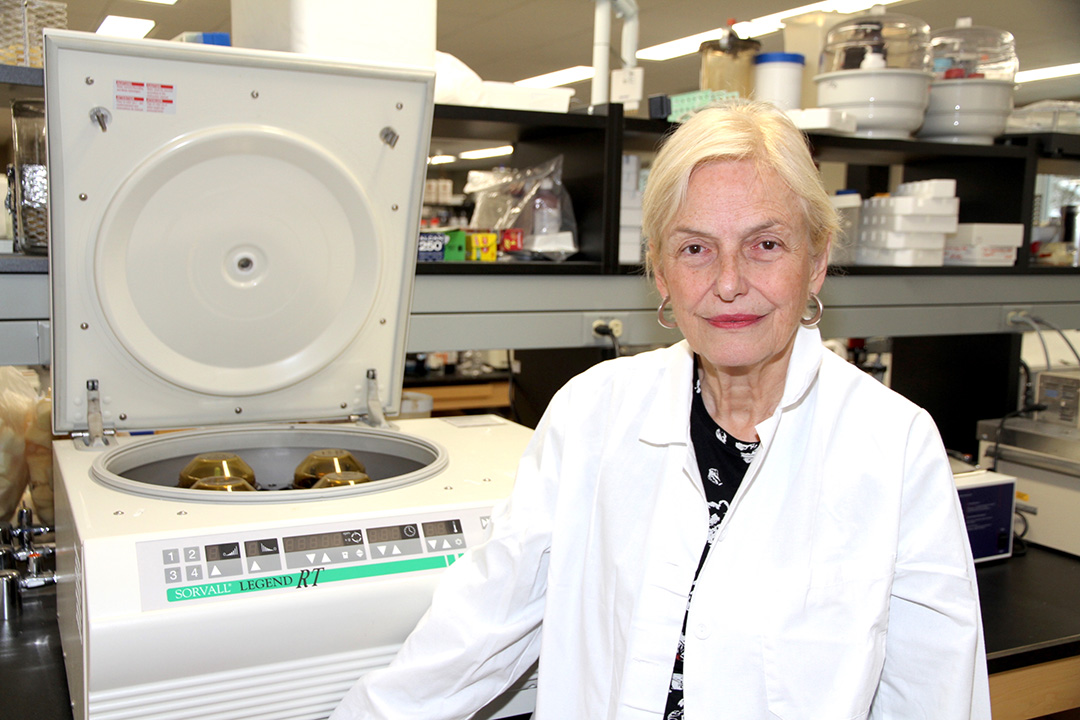

By James ShewagaUniversity of Saskatchewan (USask) researcher Dr. Jo-Anne Dillon (PhD) was part of a panel of some of the country’s top microbiology scientists who recently filed an eye-opening report on the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in bacteria and the risk it poses to Canadians and the global population.

“I’ve been sounding the alarm for 30 years on this,” said Dillon, a world-renowned researcher at USask’s Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization-International Vaccine Centre (VIDO-InterVac)—one of the largest Level 3 containment facilities in the world—and a member of the Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Immunology in the College of Medicine. “Bacterial AMR has been creeping up and creeping up for decades. And it’s a global problem.”

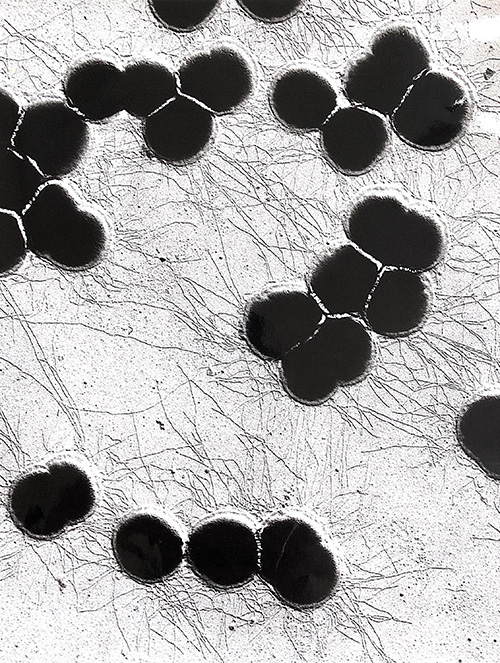

Much of the work of VIDO-InterVac researchers centres around vaccine development and rapid diagnostics for global viral outbreaks, with scientists feverishly working on a vaccine for the COVID-19 coronavirus. However, a select number of researchers like Dillon are studying the growing threat of AMR superbugs, organisms resistant to antibiotics like penicillin, with the potential to become a grave global threat.

Without effective antibiotics, the risk for patients increases dramatically, affecting everything from cancer chemotherapy, organ transplant and major surgeries, to diabetes management. And for individuals with compromised immune systems, simple infections can become life-threating. From salmonella in undercooked food and E. coli in salad recalls, to deadly staph infections in hospitals and global outbreaks of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (TB)—one of the world’s leading infectious killers—the growth of drug-resistant bacteria is becoming an increasingly global health concern.

A distinguished professor, fellow of the Royal Society of Canada and the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences, and former dean of the College of Arts and Science, Dillon helped author the federally commissioned report When Antibiotics Fail issued in November, warning of the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance to the health of human and animal populations and the potential massive costs for Canada’s health-care system.

“It’s a problem that has been developing for a number of decades and the interesting thing about this particular report is that it has a unique Canadian perspective,” said Dillon, who came to USask in 2004 after starting her research career with Health Canada in 1975. “In 2018, there were 14,000 deaths in Canada associated with resistant infections and one of the things that we did was modelling to project the potential impact up to 2050. A quarter of a million people would die if resistant infection rates stay as they are now, which is about 26 per cent. If that increases to 40 per cent, we would have almost 400,000 deaths in Canada.”

The economic impact and strain on the health-care system is also substantial.

“Right now, we think the cost of antibiotic resistance is $1.4 billion annually for Canadians, so that is sizeable,” said Dillon. “And there is a hidden cost because AMR is associated with so many different kinds of infections. We have never had an analysis like this before in Canada, so it’s not under the radar anymore.”

The landmark report by the country’s top AMR scientists has been delivered to the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Minister of Science to make recommendations. Dillon said there are a number of factors that are leading to the growth of AMR bacteria.

“Bacteria do naturally evolve resistance to antibiotics over time, but a major problem is overuse and misuse of antibiotics, and that is something that we do have the ability to control and regulate,” said Dillon. “For example, there are still parts of the world where you can simply buy antibiotics over the counter, therefore a lot of countries are trying to address that. So, stewardship is very important.”

Dillon said limiting the use of antibiotics in agriculture is also critical, a key part of the One Health Approach connection between human and animal health.

“Canada is actually restricting the use of antibiotics for agricultural use and that is absolutely huge,” said Dillon. “For example, there is a very good project going on that I am associated with, led by (Dr.) Aaron White (PhD), that is looking at resistance of E. coli in chickens and we want to ascertain how resistance could spread.”

Dillon said the majority of pharmaceutical companies aren’t investing anymore in the costly and lengthy process of developing new antibiotics, which puts the onus on government and university researchers.

“We are running out of antibiotics because there are very few new antibiotics in the pipeline right now, so there is a huge push on in terms of research to look for alternative therapeutic options, such as new vaccines,” said Dillon.

Two other weapons in the battle against AMR are increasing surveillance networks nationally and internationally and developing earlier detection procedures before outbreaks reach epidemic proportions.

“One of the things we are focused on is surveillance and rapid diagnostics to develop treatment guidelines to try to stay ahead of the curve,” said Dillon, who previously co-founded the World Health Organization’s Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. “In my laboratory at VIDO, we have done surveillance, rapid diagnostics, and mechanisms of resistance. We are trying to develop a simple test that a physician could actually detect if an organism is resistant to a particular antibiotic. This is in development. We need to invest in these areas that were pointed out in this report.”

So what can the average person do to fight superbugs? In addition to not overusing antibiotics, Dillon said the same rules for combating viral outbreaks apply to fighting resistant bacteria.

“The prudent use, and the restricted use of antibiotics is really important, and I think hand-washing, which they highly recommend in hospitals, is important, too,” said Dillon. “Just as we wash our hands to not get viral infections, we should wash our hands after handling food and being in contact with infected individuals and animals. People who live in overcrowded conditions or who are exposed to polluted water, those are also risk factors and we can mitigate some of those risk factors, too.”

However, Dillon emphasized that the growth of drug-resistant bacteria is a global problem, requiring cross-border co-operation to successfully combat the threat.

“We’re all interconnected in this,” she said. “With global travel, and importation of meat products and produce, other country’s policies affect us. A lot of people travel to countries where superbugs exist and bring them back and they are very sick. With genomics, we can now track the transmission of infections across the world. So, what is maybe a problem, for example in southeast Asia, it will most likely become a problem for us. This is a global crisis that will require a global approach.”