New parasite species found in Northern wildlife

University of Saskatchewan researchers are part of an international team that has discovered a new species of a parasite, nicknamed “Oddball,” in northern Canada’s wolverines.

By Federica Giannelli“The high levels of Trichinella transmission in wolverines in the Canadian North raise questions as to whether it could spread in terrestrial wildlife and domestic livestock harvested for food,” said USask veterinary microbiology professor Emily Jenkins.

Trichinella are tiny round worms that live in the hosts’ muscles causing fever, muscle pain and swelling. This parasite can infect animals and humans that consume undercooked or raw meat. Outbreaks are reportedly common in people eating undercooked walrus or bear in Canada. Infection or suspicion of infection in domestic livestock has to be immediately reported to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency.

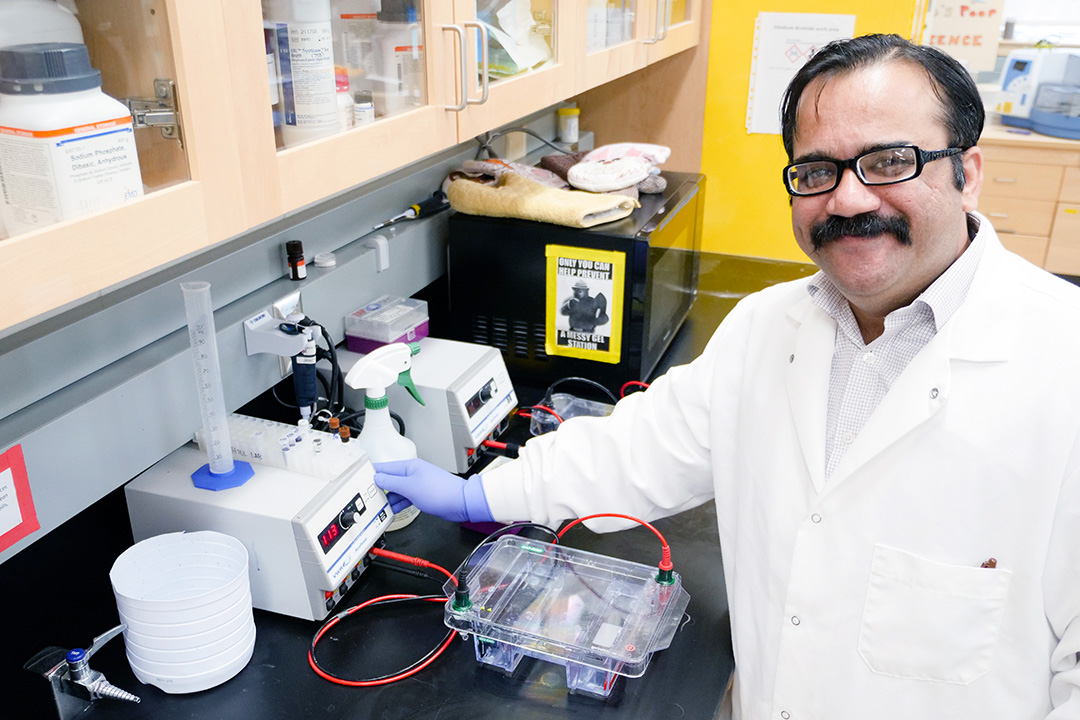

Working with Jenkins, USask PhD graduate Rajnish Sharma has found that multiple species of Trichinella live in wolverines—mammals of the weasel family—in the Yukon and the Northwest Territories. Thanks to a new genetic tool he developed, Sharma was able to identify “Oddball” as a new distinct Trichinella species.

More than 70 per cent of the almost 470 wolverine carcasses analyzed tested positive for Trichinella—T6, T. nativa, T. pseudospiralis, and T. spiralis. Wolverines likely contract the parasite when feeding on carcasses of other species such as foxes and bears.

Sharma also discovered that 14 of the wolverines hosted the new “Oddball” species.

This research, funded by the federal agency NSERC, has been presented at a major international conference in Romania, where Sharma revealed the scientific name of “Oddball”: Trichinella chanchalensis (T13). This comes from the Gwich’in name of the mountain where the parasite was found.

“The new species is very distinct genetically from other species of Trichinella previously found,” said Sharma. “Our results indicate that T13 is not geographically widespread in Canada and may be limited to wolverines in northwestern Canada, especially Yukon.”

Jenkins and Sharma suspect that T13 may have originally travelled from Russia through Beringia, the land bridge that connected Canada to Russia during the ice ages.

“To understand how T13 got in the Canadian North, future research will have to look at animals in Alaska and Siberia,” said Sharma.

The widely used genetic tool for distinguishing among species of Trichinella, called a multiplex PCR, mistakenly identified T13 as T. nativa. But while doing an internship at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Sharma developed an effective new tool that will complement current standard instruments for genetic sequencing.

Jenkins and Sharma collaborated on this project with hunters and trappers, wildlife biologists and veterinarians with the governments of Yukon and the Northwest Territories, and researchers both at the Canadian Food Inspection Agency Centre for Food-borne and Animal Parasitology in Saskatoon and the Animal Parasitic Diseases Laboratory in the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The USask researchers plan to investigate how widespread T13 infection is in wildlife, and whether T13 is freeze-resistant like the northern-adapted T. nativa and T6.

It is also concerning to the team that T. spiralis, the Trichinella species considered now eradicated in commercial swine in Canada, was detected in a wolverine near the Alaskan border. Future research will help inform authorities as to whether new health regulations should be in place to avoid new potential spillovers to and from livestock.

Federica Giannelli is a CGPS-sponsored graduate student intern in the USask research profile and impact unit.

This article first ran as part of the 2020 Young Innovators series, an initiative of the USask Research Profile and Impact office in partnership with the Saskatoon StarPhoenix.

- 30 -

Article re-posted on .

View original article.