USask researchers' in vitro fertilization successful with baby bison

It’s a rare privilege to welcome newborn bison calves into the world. It’s even more rare when those calves are the fruit of your labour.

By Lana Haight“I’m thrilled. It’s very cool to actually see something that I was able to start from an egg and then an embryo, and actually get a calf out of it. It’s very rewarding,” said Miranda Zwiefelhofer, a graduate student in the Department of Veterinary Biomedical Sciences at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Saskatchewan (USask) and a member of the research team headed by Dr. Gregg Adams (DVM).

In early July, two Wood bison calves were born at USask’s Livestock and Forage Centre of Excellence’s specialized livestock facility, southeast of Saskatoon. The bison calves are the first to be born from frozen in vitro embryos produced from immature eggs that were collected from live bison.

Adams’ team is refining protocols for advanced reproductive techniques to be used with bison in the wild. Zwiefelhofer focused on determining the ideal age and stage of development for an embryo to be frozen in order to result in a successful pregnancy.

“We can make a large quantity of embryos, but only some are capable of producing a bison calf,” she said.

Although 500,000 bison can be found in national parks and on commercial farms throughout North America, they are a “near threatened” species, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List. Rare and isolated bison genetics are locked away in remote locations. Adams and his team are determined to preserve these valuable genetics through reproduction.

Zwiefelhofer’s project started in the summer of 2019 when she and others in Adams’ team collected eggs from 32 bison cows, using minimal handling methods including sedating the bison and using field darts to deliver treatments.

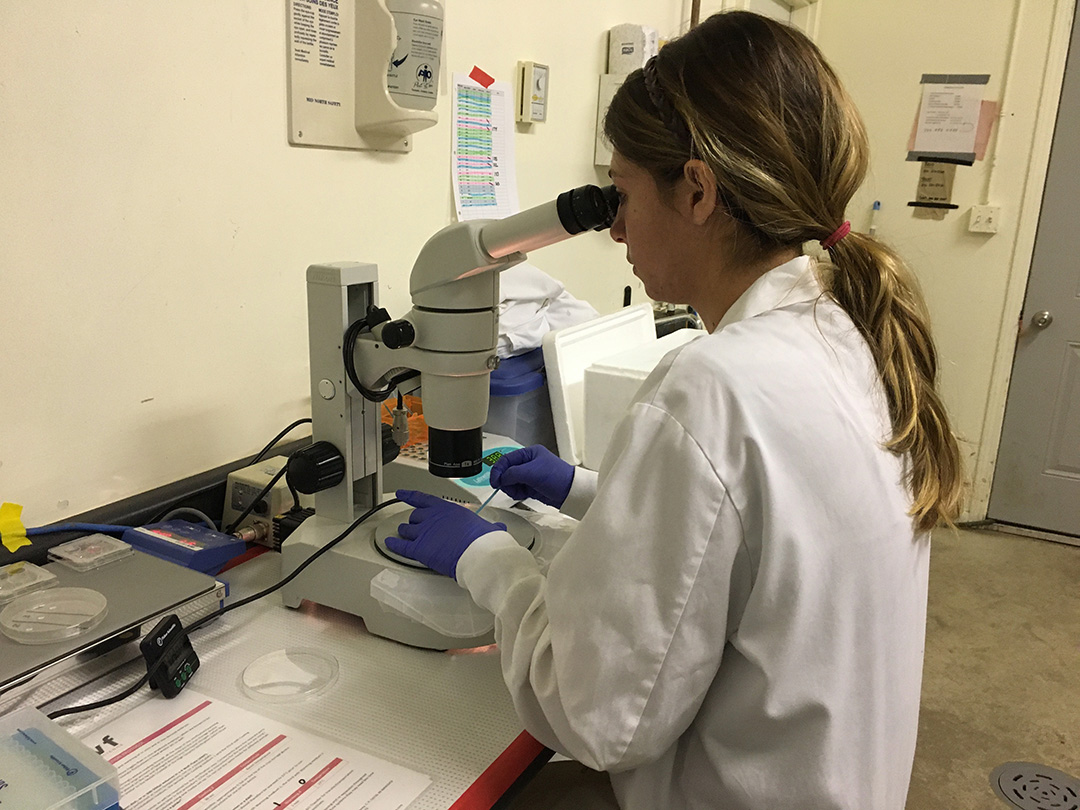

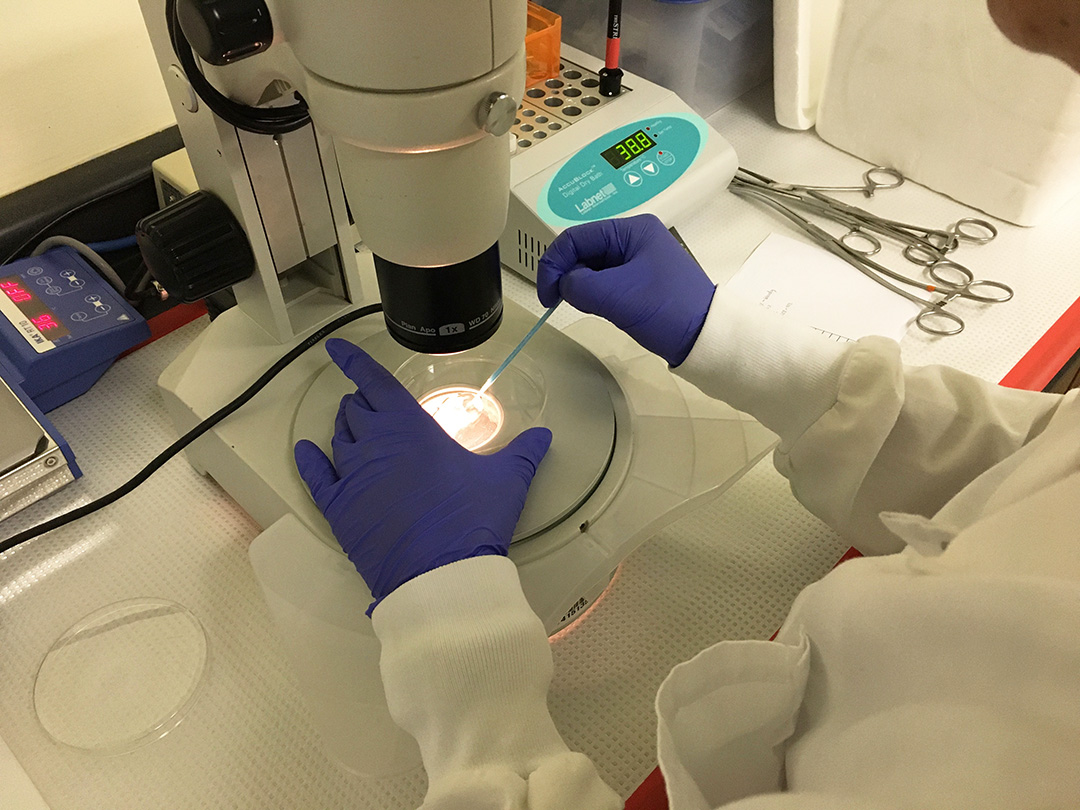

Zwiefelhofer then moved from the field to the lab. First, she grew the eggs to maturity and fertilized them with frozen-thawed semen and produced 75 in vitro embryos. Then, she observed the embryos for several days as the single cell divided into two and then four and so on until the cells became compact and a cavity formed. With different embryos growing at different rates, they were frozen in liquid nitrogen at different stages of development (from morulas to expanded blastocysts) and on different days after fertilization (seven to nine days), all critical pieces of information for Zwiefelhofer’s research.

In October 2019, the research moved out of the lab and back to the animals. Zwiefelhofer selected embryos based on the various stages of development and the age when they were frozen. She gradually thawed the ones she deemed to be of the highest quality. The team transferred embryos to 28 bison cows. When examined 30 days later, five cows were pregnant. Throughout pregnancy, three cows lost their calves. The two bison calves born were the result of morulae frozen seven or eight days after fertilization.

Like an expectant parent, Zwiefelhofer was on baby watch for days before the calves were born.

“We knew it was coming. We could see the mothers’ udders starting to fill up and getting really pink. We made sure to drive by every 12 hours starting about a week before they were born,” said Zwiefelhofer, who named the calves Skeeter and Mo.

Not only are the new calves the first bison to be born using immature eggs collected from live bison, they are only the third and fourth calves to be born from frozen in vitro embryos.

“This is a pretty big deal. That we have two calves and originally had five pregnancies shows these technologies really do work. Freezing and thawing the embryos is the difficult part. We could use fresh embryos and get a higher pregnancy rate, but to transport embryos in a biosecure manner, they need to be frozen,” said Zwiefelhofer, who is working toward earning a PhD.

With this latest research, scientists have new tools in their toolbox for ensuring the survival of pure genetics of wood and plains bison herds that are scattered throughout North America, she said.

The Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and the Saskatchewan Agriculture Development Fund contributed funding for this research.