The quest for a solution

USask's VIDO emerges as Canada's leader in vaccine development

By Joanne PaulsonOn Dec. 31, 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) was alerted to a mysterious case of pneumonia with an unknown cause on the other side of the world.

Dr. Volker Gerdts, director and CEO of USask’s Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization (VIDO), had been in his role for just under a year when the news broke. As a scientist with a veterinary degree and doctorate in virology and immunology from his home country of Germany, he was not surprised.

But he was alarmed.

“We were all following it and the news showed more and more cases,” Gerdts said in an interview. “The first weeks of January is when I thought this is not good. This could be another SARS.”

It was, and then some. Shortly after the genome of the virus, originally called 2019-nCoV, was quickly mapped by a Chinese scientist, Gerdts and his team at VIDO initiated a response.

“The day the sequence was released, I met with Darryl [Falzarano, lead scientist] and that afternoon we decided to get going on developing a vaccine,” Gerdts said. “I allocated some internal resources for the project and told Darryl to go for it."

And so began the controlled chaos, the sacrifices and the victories at VIDO, all in the pursuit to help end a pandemic that would ultimately change the course of history.

Finding the virus

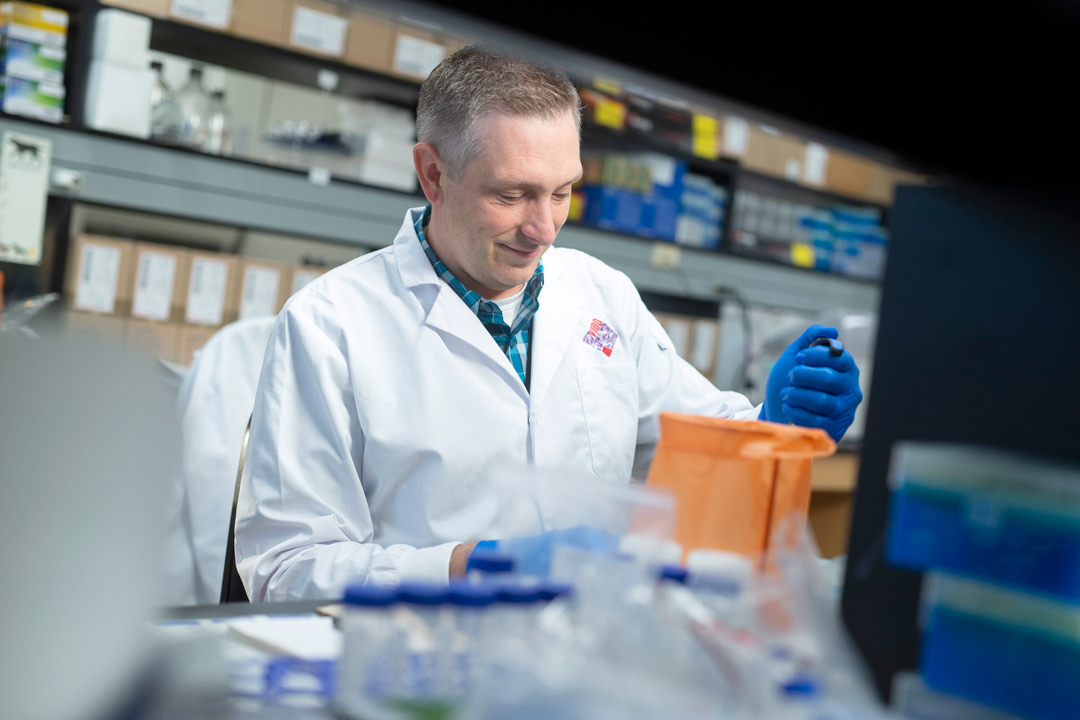

Dr. Darryl Falzarano admits he was already sporting a few grey hairs before the pandemic.

He’d already had an intense career since graduating with his PhD in medical microbiology from the University of Manitoba, which included an Ebola project at the National Microbiology Laboratory of Canada in Winnipeg. (Go Jets, he interjects.)

His post-doctoral work came at Rocky Mountain Labs in Montana — initially on Ebola and later on Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), which emerged in 2012.

“I ended up deployed in West Africa, to Liberia during the Ebola outbreak of 2014, to do diagnostics work and shortly thereafter I returned to Canada to work at VIDO,” Falzarano said.

Once at VIDO, known for its groundbreaking work with animal diseases, he started working on MERS coronavirus, the virus that causes Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Because MERS likely arises from camels, “and camels are kind of hard to find in Saskatoon,” Falzarano used alpacas for testing vaccines.

Like Gerdts, he also saw the report on New Year’s Eve, 2019. The vaccine conversation with Gerdts soon followed, and eventually they located a virus sample.

Falzarano, responsible for leading VIDO’s coronavirus lab “big-picture wise,” instantly pivoted from MERS to his new coronavirus. He was the first scientist in Canada to isolate SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19), essentially making it available for vaccine development.

“From the first identified Canadian case we were able to isolate the virus at VIDO,” Falzarano said. “We were the first Canadian lab to be able to grow SARS-CoV-2. That kickstarted everything we did.”

They received 100 microlitres of a clinical sample obtained from Sunnybrook Health Sciences and the National Microbiology Laboratory. This small amount which left them questioning: would they use it at all at once to try and isolate the virus?

“We used half the first time and didn’t get the virus to grow, so we had half left. I was hemming and hawing over what to do. Do I try the same thing again, do I try something a little different? And so I tried something a little bit different that no one else had tried . . . and that worked.”

From there, the preclinical work began. All day. Weekends. Late nights. Falzarano described those months as chaos; controlled chaos.

Despite the responsibility, he says he sleeps well, often falling into bed exhausted. But there are more grey hairs.

“In the early days, there was one point where my daughter, who was in Grade One at the time, asked my wife if I was away on a trip somewhere. My wife said, what do you mean? And my daughter said, well, I haven’t seen dad in five or six days.

"I sort of thought it through and thought I’d better have breakfast with the kids in the morning.”

The word spreads

As Falzarano and his colleagues continued their vaccine crusade, word of VIDO’s influential work began to spread. Funding announcements came in March and April as Canadians realized the dire need to be able to develop and manufacture vaccines in Canada.

The busiest months were June through November 2020, Gerdts said. Making the vaccine was the easiest part. Much more challenging was planning to manufacture it to the standards necessary for clinical trials.

“The regulator [Health Canada] has a number of requirements to ensure that a vaccine that goes into humans is safe,” he said.

Speed, as well as safety, was crucial. VIDO ordered the necessary components to make the clinical grade vaccine, while also doing preclinical research and responding to outside research requests.

“That’s what created the pressure on all of us. Instead of doing things sequentially, we did them in parallel to speed up the development . . . and also partnering with groups outside VIDO because our own manufacturing facility isn’t up and running yet,” said Gerdts.

On top of it, VIDO was inundated with requests from companies from around the world wanting to use their animal models and high containment facility, among few in Canada that can work with the virus, to test their vaccines, antivirals and therapeutics in established animal models of disease.

“Suddenly we had people involved in contract research and at the same time were running our own trials. That’s where the weekends and long nights came in,” said Gerdts.

Animal models

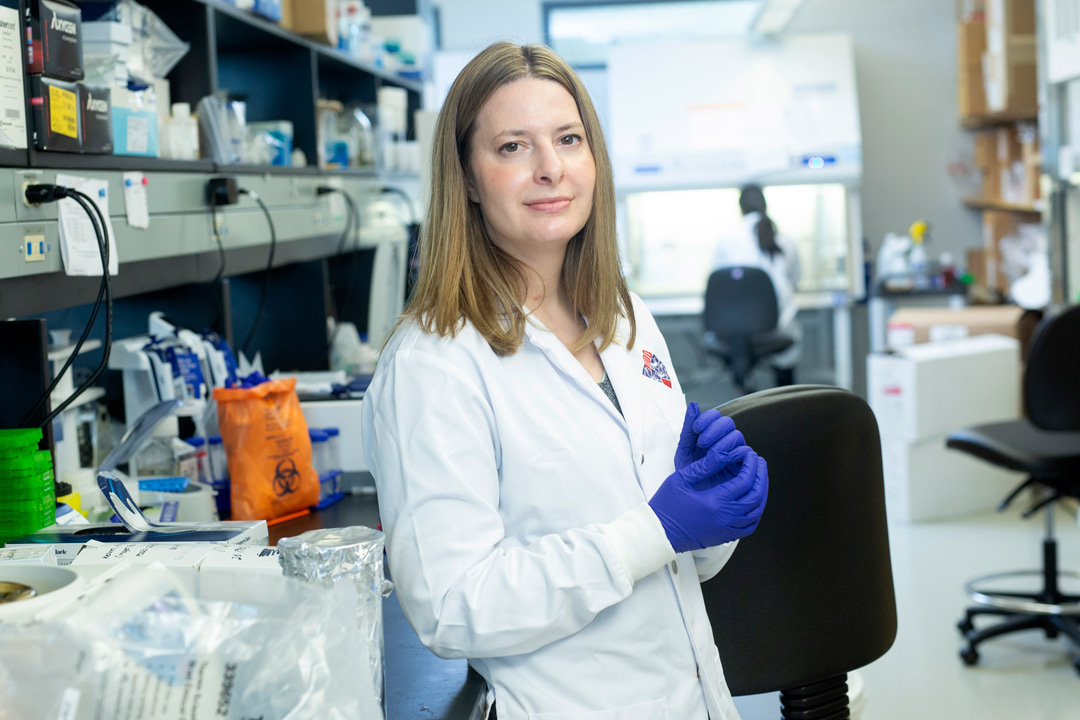

Dr. Alyson Kelvin is an expert in emerging viruses.

After attaining her Bachelor of Science from Western University, she was on the front lines of the SARS outbreak in 2003, helping screen employees at Toronto General Hospital and testing for immune responses. She also was involved in an influenza project in Sardinia, Italy, studying migrating birds and their potential for the next pandemic source. She completed her PhD in immune responses to infection and cancer at Queen’s University in the U.K.

Toronto-born, she had recently opened her own influenza research group at Dalhousie University in Halifax when COVID-19 hit. Then, she saw an alert that would forever change her life.

After hosting her family for Christmas, she had a quiet evening, her first alone for some time.

“I got into bed, checked my email one last time and at the top of the inbox was an email from what I call the social network for infectious disease geeks.

“The subject was, ‘undiagnosed pneumonia out of Wuhan China.’ Because I work on respiratory viruses and emerging respiratory viruses, immediately I wanted to know what was causing pneumonia in people leading to their hospitalization,” said Kelvin.

The WHO’s announcement on the virus came the next day. The following week, she contacted VIDO.

“VIDO always seemed like this wonderful place in my mind. I had never been here. But they had all these capacities . . . to work with a higher containment level than what I had at my institution and the capabilities for working with many animal models. To me this was amazing.

“I spoke to them about how we could get the virus into VIDO, how I could (use) my ferret model and when I could come to do some training and to work in their facility.”

By the end of February, Kelvin was on her way to VIDO with two colleagues for what she thought was going to be a two-and-a-halfweek stint.

“I think we underestimated how large the problem was,” she said, with a rueful laugh. “At the same time, we were ahead of the curve. The pandemic wasn’t declared until mid-March. Nobody was taking this disease seriously.”

But VIDO was. Kelvin chokes up as she remembers deciding she had to stay at VIDO and leave her family behind.

“By the time I was supposed to leave (Saskatoon), I knew I didn’t want to. I got on a plane, went back to Halifax, saw my family and came back (to Saskatoon) a week later. I’ve been here ever since.”

She was separated from her husband and children for six months, but they have since moved to Saskatoon.

“They came in August and we decided to make this permanent. We started as a secondment where I was supposed to be here for a year to help with the pandemic efforts, but I love working here and the incredible opportunities at VIDO, so I applied for a scientific position at VIDO and am happy to report I am staying.

“I really can’t imagine doing anything else. I couldn’t have been at home not doing what I was trained to do. It just seemed absolutely wrong.”

Canada’s Centre for Pandemic Research

In April 2021, Canada’s federal government released its annual budget. The government announced $59.2 million in funding for VIDO, but this time it was not for vaccine development — it was to create a National Centre for Pandemic Research.

VIDO had already received $11 million from the Canada Foundation for Innovation - Major Science Initiatives Fund for operating InterVac, Canada’s largest high-containment lab, and an additional $12 million to help fund VIDO’s biomanufacturing facility.

Of the new funding, a large portion was tagged for the construction of a new animal facility and to upgrade VIDO’s containment space to Level 4 — the highest biosafety level. The federal funds were in addition to the $15 million commitment from the Province of Saskatchewan and $250,000 from the City of Saskatoon. All three levels of government supported the National Centre.

“Having containment Level 4 will allow us to work with any new pathogen, whether it’s human or animal. We essentially will have the capacity to respond to any new disease immediately,” said Gerdts.

The funding confirms the vision of VIDO becoming Canada’s Centre for Pandemic Research, and it’s what Gerdts is the most excited about.

“This is really the fulfilment of VIDO’s and the university’s vision, in that area. It’s taking human and animal health to the next step, and now we have a centre on campus that becomes one of Canada’s key players in responding to emerging infectious diseases and is globally connected to all these international efforts. That’s the vision I always had for VIDO and that’s what I’m seeing becoming a reality now.

“We’re aggressively fundraising and recruiting right now, looking for the best people we can get. That is the most exciting part in all of this. We’re taking VIDO to the next level from a scientific, expertise and reputational point of view. It’s really playing in another league,” said Gerdts.

Clinical trials

The vaccine was shipped to Halifax in February, 2021 and Phase 1 clinical trials began shortly after. Samples from the vaccinated people came to VIDO shortly before the federal funding announcement. It was a big month.

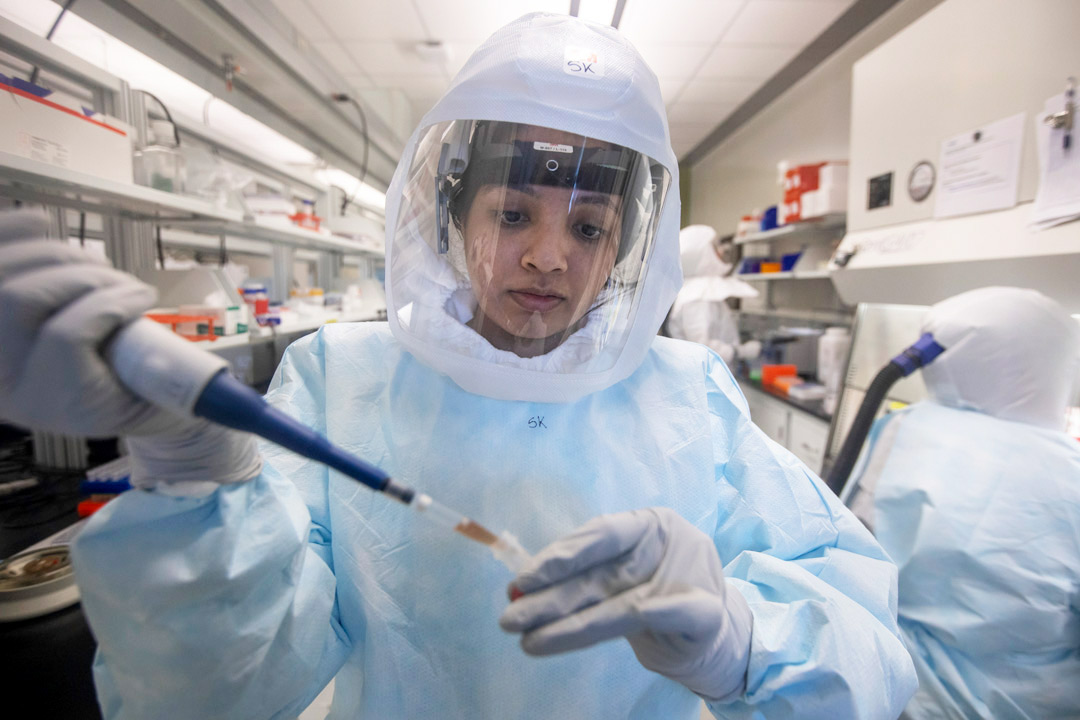

Fully ensconced in what she calls her “space suit,” the personal protective equipment (PPE) used in Level 3 containment, Jill Van Kessel (BSc'92, Sc'97, MSc'06) enters the lab daily to evaluate the immune responses of those vaccinated with VIDO’s COVAC-2 (Coronavirus Vaccine 2).

Van Kessel, a USask graduate with a microbiology and immunology degree, joined VIDO on a six-month term shortly after her daughter was born and returned nine months later to join the virology group, while also taking her master’s in veterinary microbiology.

“I started working with Volker in the immunology group and was there until last January. That’s when I volunteered to help with the COVID research,” she said.

“At the time it was kind of surreal. You’re watching the news and it started to get more serious and you’re watching things evolve in Europe and how bad it was getting in Italy, but the virus hadn’t really arrived in Canada yet. It was there, but not real.

“But then when WHO declared it a global pandemic and governments shut everything down, that was very, very strange. We were still coming to work, but the campus was empty, the roads were empty, there’s nobody in the parking lots. It was kind of apocalyptic.”

The high level of PPE has also taken a bit of adjustment, since she is in it every day. But the importance of the work has overridden all concerns, despite the incredibly long hours.

“This last year has been very stressful for all of us in the lab. The work came so fast and so heavy. But it’s important so you have to get it done.

“It’s really exciting. It means something . . . people are dying and you have the potential to make a difference. It was very exhilarating but also very draining because there’s a lot of pressure that goes along with that.

“It’s amazing that we have our vaccines in clinical trials. Getting those samples in and being able to analyze them and see how it’s working, that’s really exciting too.”

Vaccine benefits

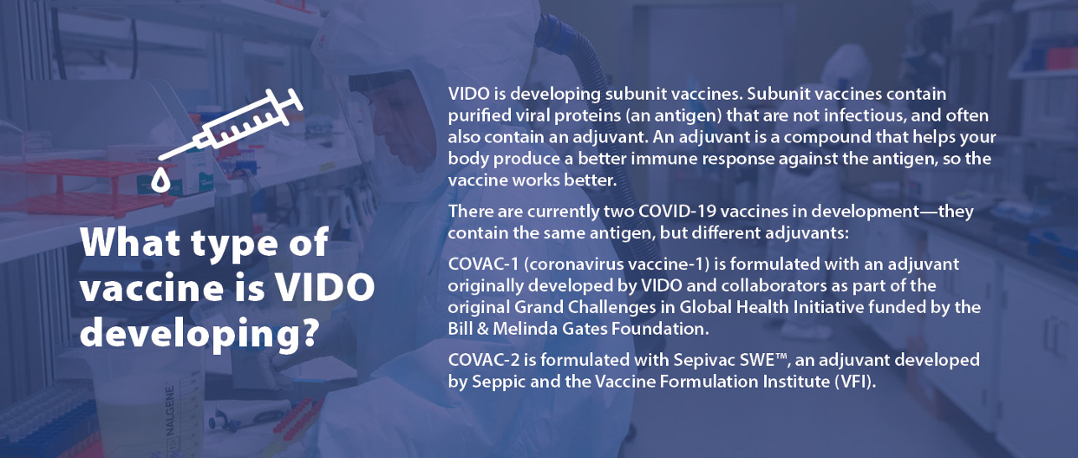

VIDO’s COVID-19 vaccines are expected to have several benefits, Gerdts says.

This could include efficacy against variants and are based on a proven technology, “which historically has an excellent safety profile, so some of the safety concerns including blood clots shouldn’t be an issue with our vaccine... Lastly, the cost may also play a role; it will be probably more affordable than some of the other candidates.

“We envision our vaccine to be something that can be used annually in a booster. We’re also looking at this vaccine as a potential candidate for low- and middle-income countries. Our vaccine would have several advantages like storage and transportation for (places) like Africa.”

MERS advances COVID-19

It’s likely that none of this would have happened so quickly if it hadn’t been for VIDO’s expertise in other coronaviruses including MERS, says Falzarano. VIDO has also developed vaccines for bovine and porcine coronaviruses and played a role in the SARS Accelerated Vaccine Initiative.

VIDO could pivot to COVID-19 quickly because it had spent years working on coronaviruses including MERS, despite some quarters wondering why. MERS was a Middle Eastern problem; why was a Canadian institute working so hard on it?

“For two reasons: in case MERS does arrive in Canada, as happened in South Korea, we know how to respond; but secondly, we know new coronaviruses continue to emerge so what we learn and technologies we build that apply to other ones help us respond to a new one,” Falzarano said.

“Other places that had not been working on highly pathogenic coronaviruses . . . some of them took months to get to the spot where they were allowed to work on SARS. It’s not because their facility wasn’t capable of handling this virus; it was because they didn’t have the experience, the documentation, the training to do that immediately.

“When we asked for permission from our regulatory agencies to work on SARS-CoV-2 , given our experience with MERS, the answer was given one day later.

“Yes.”

The latest news

On June 23, 2021, VIDO announced positive interim results from their Phase 1 clinical trial for COVAC-2.

Much can change between the time this article was printed and the next phase of VIDO’s vaccine journey.

Make sure to stay up to date with all the latest information by visiting VIDO.org – including how you can donate to our Friends of VIDO initiative and contribute to Canada’s Centre for Pandemic Research.

Article re-posted on .

View original article.