Lentils first breakthrough in CDC history of re-shaping Prairie agriculture

It’s hard to imagine what Saskatchewan’s pulse industry would be like today if the University of Saskatchewan’s Crop Development Centre (CDC) had never been created.

By Kathy Fitzpatrick for USask Research Profile and ImpactThe CDC has “played a very important role in helping to foster the growth of the sector here in Saskatchewan,” said Carl Potts, executive director of Saskatchewan Pulse Growers (SPG).

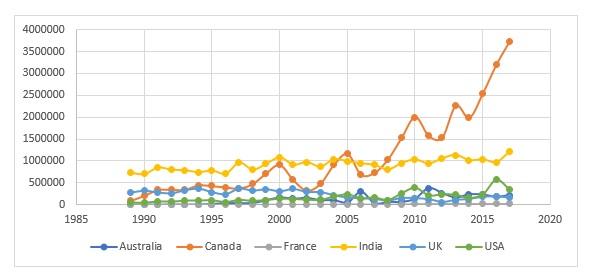

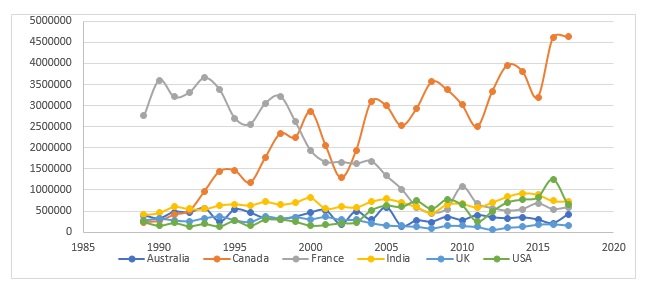

Lentils, an inexpensive and nutritious source of protein, are Exhibit A in this success story. Nearly all the country’s production comes from Saskatchewan, and Canada is the world’s top producer and exporter.

2020 was a banner year for lentils: the volume of Saskatchewan’s lentil production shot up by almost 26 per cent over the previous year, overtaking oats, while seeded acres of lentil increased by more than 12 per cent.

But when pea breeder Al Slinkard arrived at the CDC in 1972, lentils were almost unheard of as a viable crop for Saskatchewan. Slinkard stood that notion on its head, and for that he was bestowed with numerous awards. In November of 2020, he became an honourary member of the Order of Canada.

When Slinkard arrived from the University of Idaho, a global wheat surplus had driven prices down and there was a need to diversify. Slinkard learned of a couple of Saskatchewan farmers who had tried growing lentils unsuccessfully. On top of that, the price was “ridiculous”, Slinkard recalled: four cents per pound.

But in 1978, the year the Laird lentil Slinkard developed was released, the Palouse area straddling Washington and Idaho states suffered an “unprecedented drought”, he said. Buyers turned to Saskatchewan, and the average price shot up to 35 cents per pound.

Bruce Cheston, a farmer in the Grand Coulee area west of Regina, had grown two fields of lentils with a yield of 1,800 pounds per acre, grossing more than $600 an acre, whereas the wheat grower across the road (would be) “lucky to get $100,” Slinkard said.

That winter Slinkard criss-crossed the province giving talks to farmers three or four times a week, finding an eager audience. By the late 1980’s, Slinkard was able to report that the Laird lentil “is the most widely grown lentil variety in the world.”

The large-seeded Laird was quickly followed by Eston, a small-seeded green lentil, released in 1980.

“Growers at the time recognized that in order to have a successful and growing industry, they needed to make investments in support of breeding,” Potts said. Since 1997, SPG has invested more than $60 million at the CDC in support of plant breeding and related research including genomics.

Today, not only does Saskatchewan’s pulse industry enjoy global reach, so does the CDC’s ongoing research into pulse crops.

An international team led by CDC plant scientist Kirstin Bett has developed a model for predicting which lentil varieties are most likely to thrive in new production environments. It’s vital information for producers and breeders as they strive to address climate change and feed the world’s growing appetite for inexpensive plant-based protein.

Working with universities and organizations around the world, the team planted 324 varieties in nine production hotspots throughout North America, South Asia, and the Mediterranean. The findings have been published in 2020 in the journal Plants, People, Planet.

The CDC’s Bett and Bert Vandenberg are also working with the genomic big data company NRGene, based in Israel but with an office in Saskatoon, to sequence several of the world’s major crops.

In 2017, the partners reported they have successfully sequenced two wild lentil genomes, information that will further breeding efforts to enhance yield and quality. That work is part of a $7.9-million Genome Canada-funded project to apply genomics to “innovation in the lentil economy.”