Global water basins hotspots prioritize areas under threat: USask research

New research at the intersection of how humans and ecosystems interact with water shows that the most-stressed regions in the world are becoming drier leading to water governance, economic and social challenges.

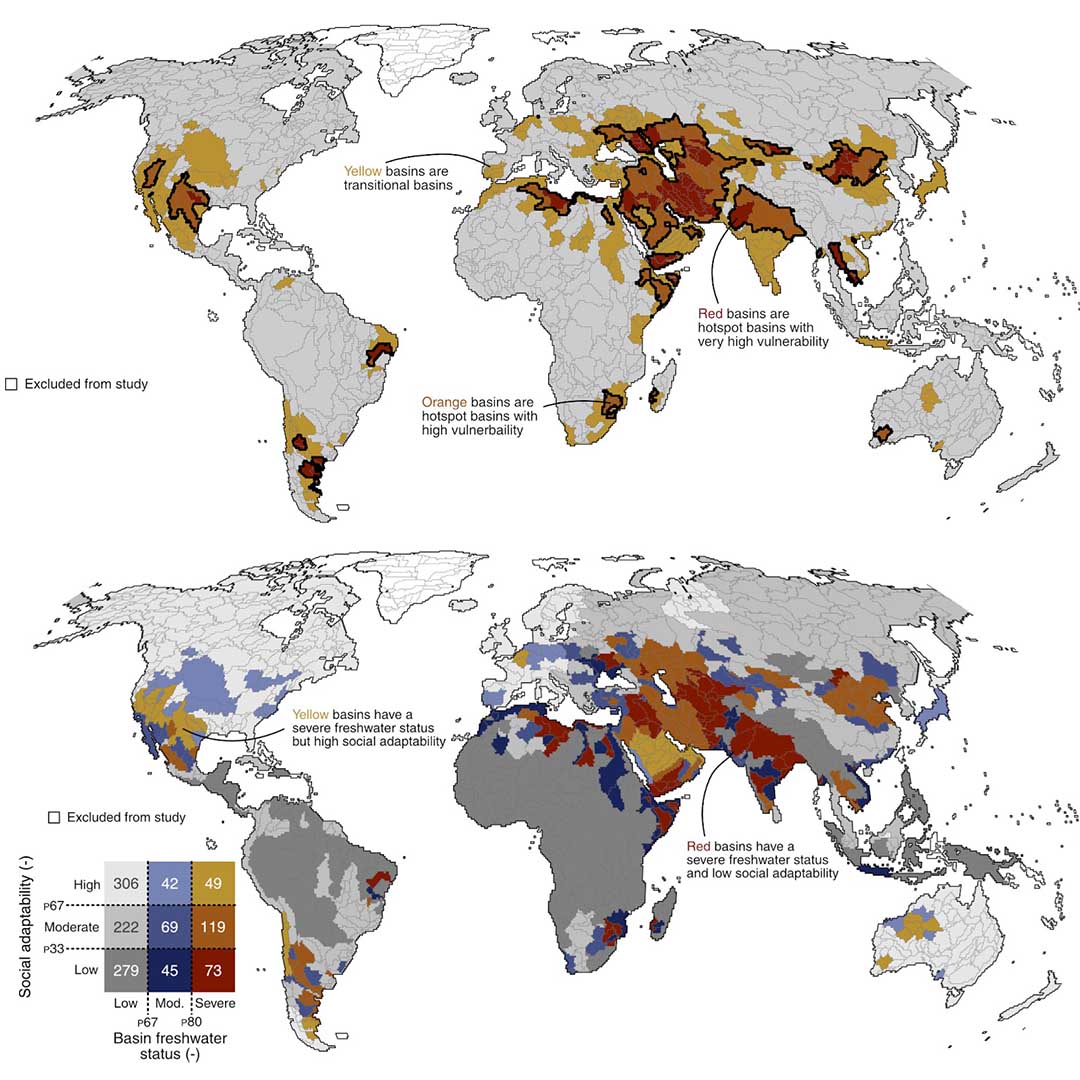

Recent studies involving a University of Saskatchewan (USask) researcher show where groundwater is becoming less available globally, but less work has been done to understand the impact changes to these water systems have on people. That is where a new study, which was recently published in Nature Communications, takes into account both social and ecological impacts, allowing researchers to identify global “hotspots” where the threat to the water basin is most concerning.

“There’s a consensus in sustainability science and sustainability literature around being wary of broad-brush solutions,” said Xander Huggins, a PhD candidate with USask’s Global Institute for Water Security (GIWS), and the University of Victoria Department of Civil Engineering.

“These [solutions] really need to be generated locally, and they will be different from each other from place to place. … This gives us a template for where to focus globally with greater specificity.”

Huggins, the lead author of the paper titled Hotspots for social and ecological impacts from freshwater stress and storage loss, says this is “a call to action,” and there’s already been interest in the research from non-governmental organizations such as the World Wildlife Fund.

Once the vulnerable water basins are clearly identified, place-based solutions can be implemented by local communities, organizations and governments.

“There is an urgent need to address these drying water basins. The most vulnerable basins impact more than 1.5 billion people, 17 per cent of global food crop production, 13 per cent of global gross domestic product, and hundreds of significant wetlands,” said Huggins.

He said one of the ways governments and communities can address this crisis is to apply integrated water resources management (IWRM), a process that promotes co-ordinated water management and is tied into the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

The study suggests that basins with low levels of IWRM where vulnerability is high should be the priority basins. Yet comparing the vulnerability mapping they produced to the current level of IWRM implementation, they found that transboundary basins — shared by multiple countries — are the least likely to implement such measures and are also the most at risk. Nations with low levels of IWRM implementation and very high vulnerability include Afghanistan, Algeria, Argentina, Egypt, India, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Mexico, Somalia, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, and Yemen.

“Part of the reason why they are so vulnerable is that there's less diplomacy … between these multi-jurisdictional water systems that are affecting humans and ecosystems at once,” Huggins said.

The paper calls for greater policy integration and hydro-diplomacy, noting that of the nearly 700 water conflicts documented since 2000 by The Water Conflict Chronology, two-thirds (68 per cent) are found within either transitional or hotspot basins.

Jay Famiglietti, executive director of GIWS and co-supervisor for Huggins’s PhD work, says the research helps prioritize the attention that these different basins need.

“The work we’ve done until this point has been strictly looking at water availability and changes in water availability, and we've only talked in broad strokes about how it might impact food production, how it might impact biodiversity, what it means for political stability or conflict,” Famiglietti said.

“This is really the first step at putting a few of those other stressors together, along with changing water availability, to get a more robust picture of just how vulnerable these basins are.”

Looking to the future, Famiglietti, Huggins and others are putting together an international, transdisciplinary group to address the problem of global groundwater sustainability, and Famiglietti said research like this is critical to moving forward.

“You really have to understand the social structure, the governance structure, the biodiversity that's at risk, the wealth of the nation, its capacity,” he said. “This is really the first step towards that diagnosis.”