USask chemists solve 27-year-old riddle, produce promising new compound

University of Saskatchewan (USask) chemists have successfully produced for the first time a new, stable organic compound which has eluded other scientists for more than 27 years.

By USask Research Profile and ImpactWhile researchers theorized in 1995 the existence of a stable form of [10]annulene, a flat ring of 10 carbon atoms which are attached together by alternating single and double bonds, it has proven impossible to produce in the laboratory—until now.

“We had champagne,” said Dr. Michel Gravel (PhD), lead researcher and professor of chemistry at USask’s College of Arts and Science. “We did not wait for the publication to be accepted to celebrate. We definitely had a celebration when we observed the molecule for the first time.”

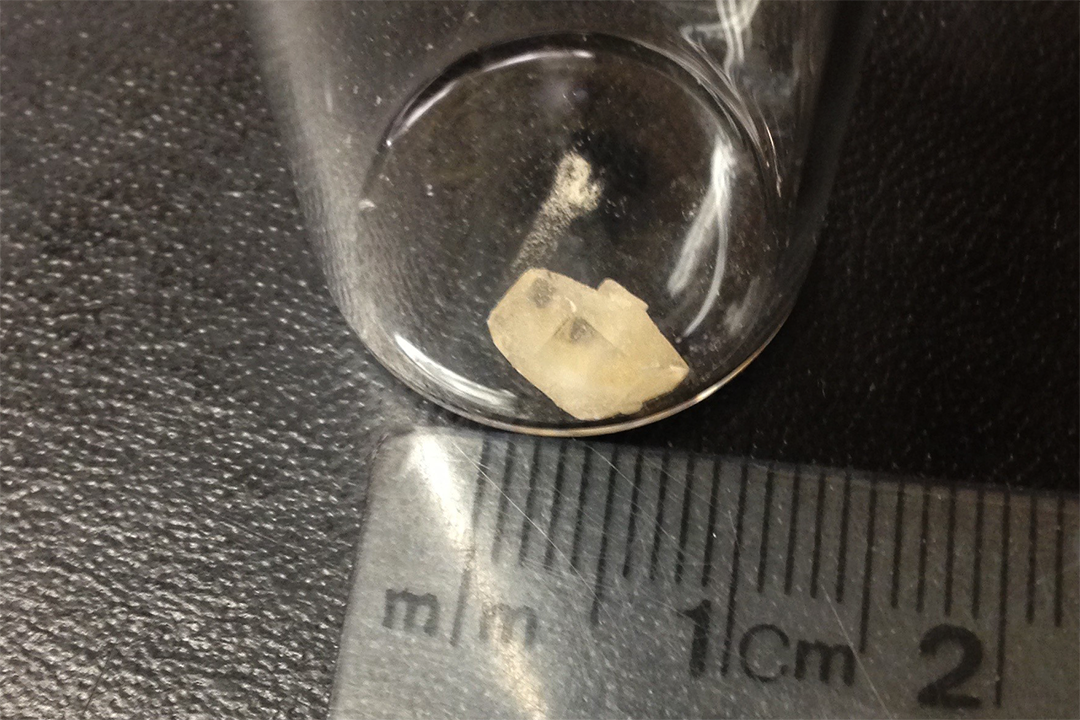

The compound is a clear, colourless liquid at room temperature, absorbs ultraviolet light, and involves a complex 12-step process over multiple months to produce. To make only 10 milligrams of the [10]annulene it requires 1,000 times that amount of starting material.

“Our synthesis is inherently very inefficient,” said Gravel. “What's remarkable, what people are excited about, is that we were able to make it at all.”

The results, which were published in the journal Nature Synthesis, are the culmination of an iterative, eight-year process for Gravel, who worked with two graduate students, Dr. Karnjit Parmar (PhD) and Christa Blaquiere, and two undergraduate students, Brianna Lukan, and Sydnie Gengler.

“It’s a liquid that’s rather volatile. If you left it on the countertop, it would be all gone by morning,” said Gravel.

The compound has potential to replace benzene—a six-carbon ring structure—in many applications, including as an organic semiconductor for use in electronics and solar panels. First, Gravel needs to produce more of the substance to better investigate its properties.

“Perhaps it will last longer, perhaps it will conduct better. We don’t know yet,” he said.

While the properties of many compounds can be forecast using computer modelling, for [10]annulene and other so-called “aromatic” molecules—those with alternating single and double bonds—computation has not caught up with experimentation. Scientists must produce the compounds to examine them.

Gravel is working on a new pathway to make this and other [10]annulenes more efficiently, reducing the number of steps from 12 to three or four, and increasing the output yield.

“If everything goes well, we’re looking at a few months to produce the compound using the new pathway,” said Gravel. “If things don’t go well, maybe never.”