USask honours Wastewater Surveillance Team for public engagement

The University of Saskatchewan (USask) Wastewater Surveillance Team, which responded swiftly to the arrival of COVID-19 by developing a monitoring program that provides reliable forecasts of infection outbreaks in communities, is being recognized with USask’s 2022 Publicly Engaged Scholarship Team Award.

By Sarath PeirisThe award is presented annually to faculty members, post-doctoral fellows, graduate students, and/or community partners in recognition of collaborative efforts to combine their knowledge and produce an outstanding social impact locally, nationally, or internationally.

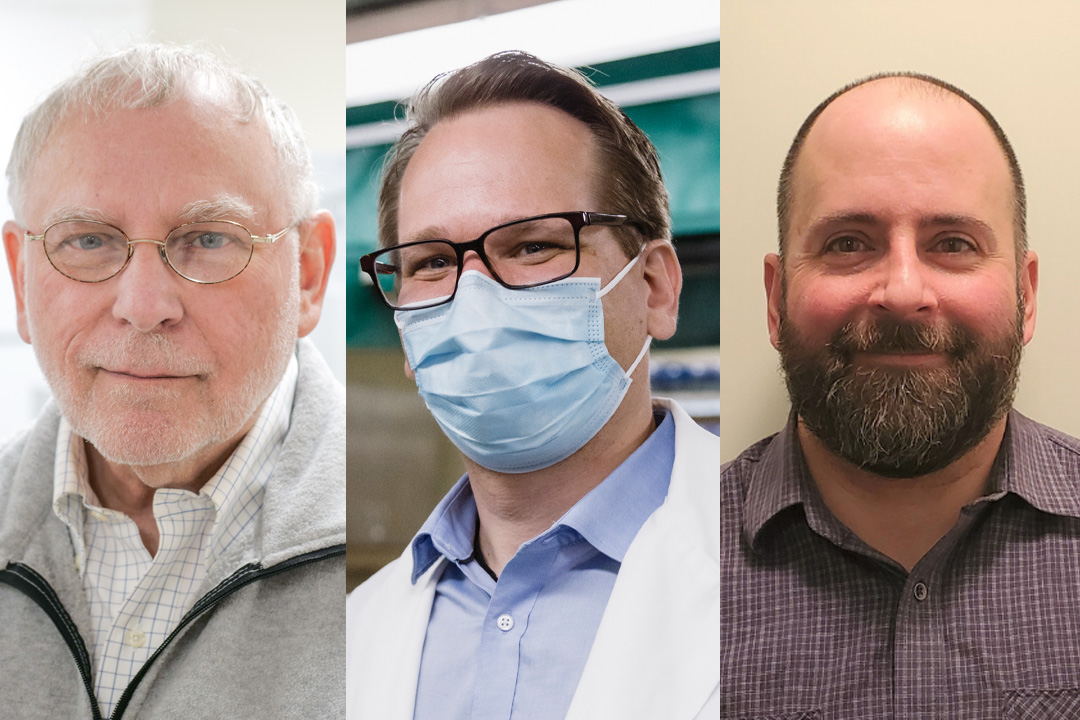

The public faces of the wastewater team are Dr. John Giesy (PhD) of the Western College of Veterinary Medicine, Dr. Markus Brinkmann (PhD) from the School of Environment and Sustainability, and Dr. Kerry McPhedran (PhD) of the College of Engineering, who are all members of the Global Institute for Water Security (GIWS) at USask.

“We are all very grateful for this award, but I want to stress that the credit must be shared with our entire team, who didn’t hesitate to step up and contribute to help Saskatchewan deal with the arrival of COVID-19,” said Giesy.

Other team members are toxicologist Dr. Paul Jones (PhD), post-doctoral fellow Dr. Yuwei Xie (PhD), environmental engineer Dr. Mohsen Asadi (PhD), and research associates Dr. Femi Oloye (PhD) and Jenna Cantin.

The diverse team has gained national attention with its online dashboard—one of the first worldwide—that presents COVID-19 wastewater surveillance results that indicate virus status and trends for the cities of Saskatoon, Prince Albert, and North Battleford. The frequently visited website is considered the sole source of reliable COVID-19 trend data, with the Saskatchewan government no longer providing clinical testing, in favour of publicly unreported self-testing.

The team findings provide a reliable leading indicator of impending surges or declines of COVID-19 infections by seven to 10 days and helps to identify the presence of new variants.

Giesy said his experience in 2003 with the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in Hong Kong during his sabbatical there prepared him to respond quickly to the arrival of COVID-19.

“Opportunities come to prepared minds,” he said. “I knew the clock was ticking, and we had to help. It was a function of being prepared and having the courage to act on the opportunity.”

Global Water Futures (GWF) permitted Giesy to pivot some funds and sophisticated technology from his ongoing environmental DNA research project to COVID-19 monitoring. He and Xie then developed a comprehensive system to detect COVID-19 gene particles in wastewater.

The accuracy of their method was validated in a comparative study with eight other labs across Canada, and the USask team became a key contributor to advancing wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE) in Canada, Germany, and elsewhere.

The team’s quick foray into wastewater testing for the COVID-19 virus was based on partnerships the researchers had built with municipalities through previous wastewater research, including Brinkmann and McPhedran’s work with treatment plant operators in Saskatoon to monitor flows for the presence of pharmaceuticals and toxic compounds from rubber tires.

And, thanks to McPhedran’s trusted partnerships with numerous First Nations as Saskatchewan Centennial Enhancement Chair in Water Stewardship for Indigenous Communities, the team monitors wastewater for three communities—a process that requires co-operation and a strong commitment to gather and transport time-sensitive samples. As well, the team has helped the USask community by monitoring flows from student dormitories.

Giesy said when his team had trouble finding long-term funding for wastewater monitoring, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) stepped up. PHAC has now extended funding to 2023 and named the USask team as its Prairie Node of a national WBE project that could see monitoring extended to include recreational pharmaceuticals, other viruses, and especially drug-resistant bacteria.

“We like to work on socially relevant issues and solve problems. Our role is to develop technologies that can be transferred to the private and public sectors and train the next generation of water quality experts,” said Giesy. “We have taken a leap of faith and good things have happened.”