USask researcher and Nobel laureate Herzberg predicted source of comet’s green hue in 1939

A comet from the outer solar system will be visible from Earth for the first time in 50,000 years – and its green shine can be explained in part by a prediction made by Nobel laureate Gerhard Herzberg at the University of Saskatchewan (USask) almost a century ago.

By BROOKE KLEIBOERComet 2022 E3 (ZTF), which will be visible in early February, has been orbiting the outer solar system for tens of thousands of years. Because of its wide orbit, the comet is only seen from Earth every 50,000 years, making it a truly once-in-a-lifetime event for skywatchers. Those in Canada looking to the northwestern skies before dawn on Feb. 1 and Feb. 2 have the best chance of seeing the comet.

“It’s important to pay attention to celestial events like this because they are often how we learn about our world,” said Dr. Daryl Janzen (PhD), an astronomy expert and instructor in the Department of Physics and Engineering Physics at USask’s College of Arts and Science. “Science itself was essentially invented because people noticed that the planets follow wandering paths through the stars and wanted to explain that.”

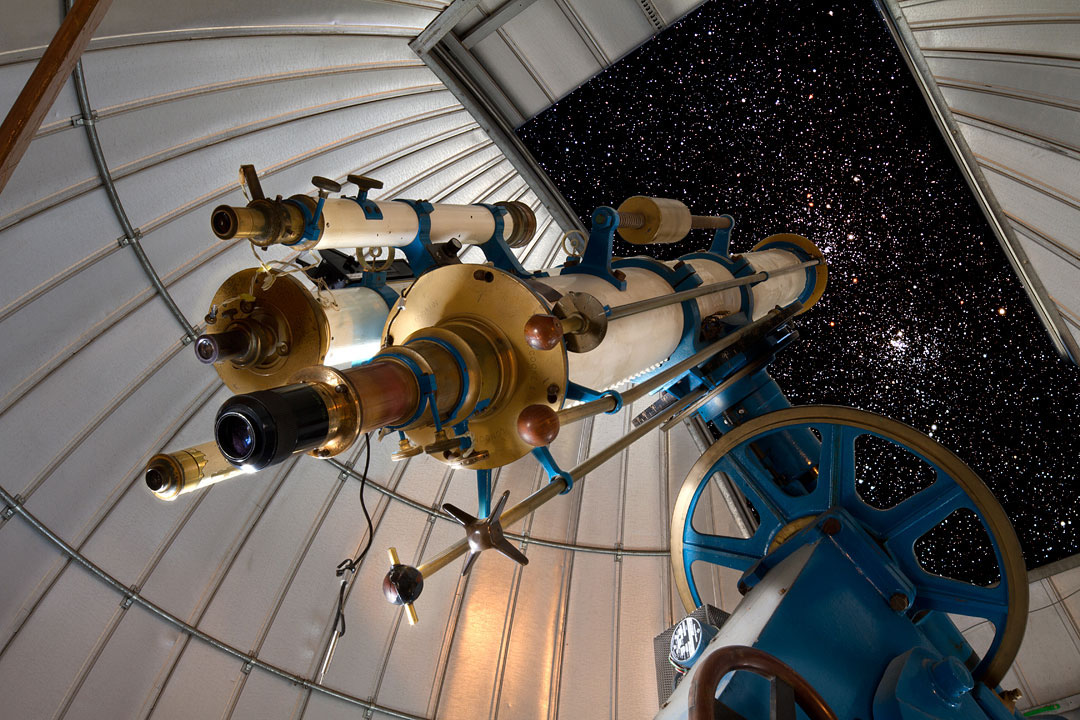

Janzen also co-ordinates public outreach activities for the USask Observatory, which is open for public viewing of celestial objects on the first and third Saturdays of each month.

Like many other comets, Comet 2022 E3 (ZTF) gives off a distinct green colour from its bright head as it arcs across the sky. The puzzle of the exact cause of this green coloration has been solved in recent years, thanks in part to Herzberg.

Herzberg, winner of the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1971 and a groundbreaking researcher who conducted much of his foundational work at USask from 1935-1945, spent his career studying the structure and geometry of molecules using spectroscopy, the study of the absorption and emission of light and radiation by matter. His studies led to innovative understandings of how molecules and atoms function and interact, and formed the basis of many advancements in astronomy, health, chemistry, and physics.

Herzberg began studying the diatomic molecule, C2, as early as 1937 while he was at USask. C2 is formed because carbon (C) is a relatively unstable element and attempts to stabilize itself by bonding itself with a second carbon molecule. His work eventually evolved into an analysis of how C2 may be of interstellar importance. A prediction Herzberg made in analyzing the spectroscopy of C2 laid the foundations for our current understanding of why colours appear in comet comas—the cloud of dust and gas that surrounds a comet’s head.

According to work published in 1939 in The Astrophysical Journal, Herzberg speculated that the cause of a comet’s green hue could be due to sunlight causing C2 to reach a high level of vibration, which causes the two molecules to break their bond and disassociate. It was thought the ripping apart of these molecules released energy emitted as a green colour.

This prediction remained unconfirmed for almost a century due to the difficulty of testing such a scenario. In December 2021, a University of New South Wales team published a research paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that tested Herzberg’s theory for the first time. Through a lab experiment, the research team showed that C2 molecules disassociate at high vibrational levels and cause a green light to emit from a comet’s coma. This discovery provided scientific proof of what Herzberg suspected back in 1939.

“Comet comas are typically green, and as Herzberg predicted, the colour comes from photo-dissociation of diatomic carbon, which is an abundant molecule in comets,” said Janzen. “This recent study confirmed that C2 has a lifetime of roughly two days until sunlight breaks the molecule apart and emits a green photon. It’s not just the colour, but this short timeframe that explains why the green light comes only from the coma and not the comet’s tail.”

Herzberg took much interest in interstellar space, and in the mysteries that could lie in outer space that may help us understand molecules and atoms and their behaviour here on Earth.

“We’ve now explained why comets have green comas because, first of all, people bothered to notice that the comas are green, and then Herzberg had an idea to explain why that is,” Janzen said. “When we pay attention to the world and see something we haven’t seen before, we are participating in the first step on the path toward scientific discovery.”

Observing Comet 2022 E3 (ZTF) as it passes by Earth in early February prompts a reminder of the scientific legacy left by Herzberg both at USask and in the world, as the skies are lit “USask green.”

Visit research.usask.ca/herzberg to learn more about Herzberg’s groundbreaking work at USask.