World Water Day: Three things to know about protecting drinking water

As the United Nations prepares to observe World Water Day on March 22, a University of Saskatchewan (USask) researcher discusses the need for water protection planning and anticipating contamination risks.

By Kristen McEwenAs water is Earth’s most valuable resource, there is a need to protect drinking water sources in communities.

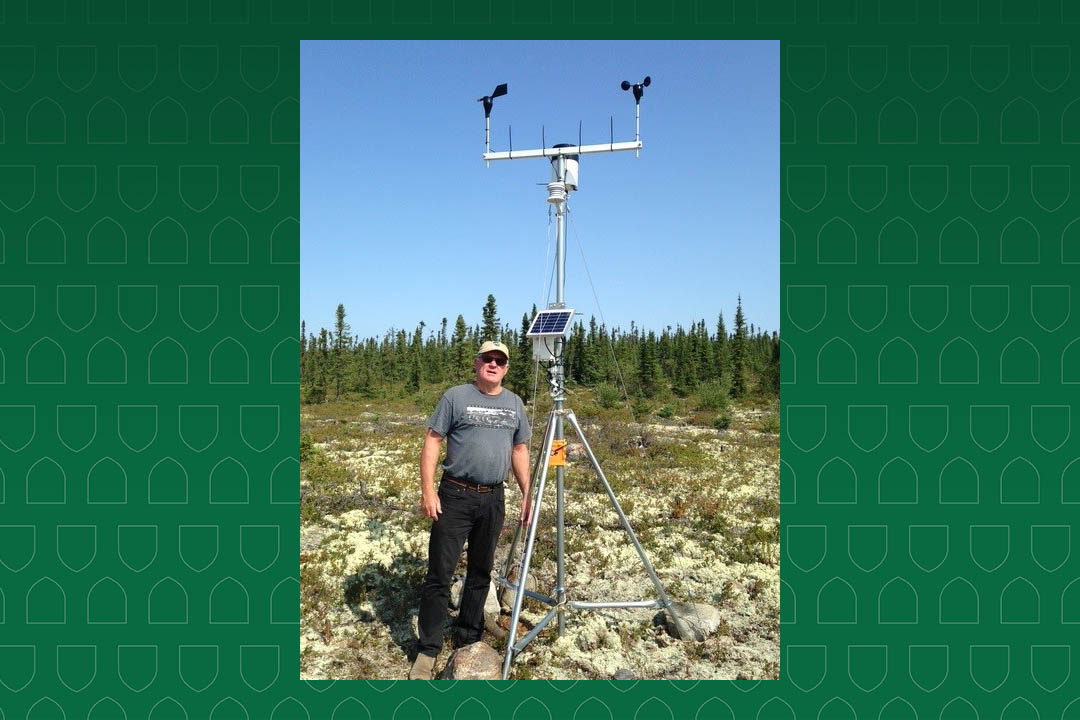

Dr. Bob Patrick (PhD), a professor in the Department of Geography and Planning at the University of Saskatchewan (USask), has spent his research career helping urban and Indigenous communities plan to protect local water sources.

He is also the chair of the Regional and Urban Planning program in the department and a member of the Global Institute for Water Security (GIWS) at USask.

Patrick shared three key things about protecting drinking water sources in Canada:

- Water protection planning entered the national spotlight in 2000

The need for source water protection plans arose from a water contamination event that impacted nearly half the population of Walkerton, Ont., — a town of 5,000 people — in May 2000.

Known as Canada’s worst case of E. coli contamination, nearly 2,300 people experienced illnesses, and seven people, including a baby, died due to water contamination in Walkerton.

An inquiry led by Justice Dennis O’Connor of the Ontario Court of Appeal was initiated to determine the cause of the tragedy and how to avoid an incident like this in the future.

“The outcome of that inquiry was that there must be greater attention given to source water protection to lessen the threat of contamination. In fact, the first 13 of the 93 recommendations from the inquiry directly reference source water protection as the first barrier in the multi-barrier approach to safe drinking water,” Patrick said.

While the Walkerton tragedy was a wake-up call for most Canadians, many First Nation communities across Canada had been experiencing drinking water contamination events for decades, he added.

Patrick assisted the Government of Canada and the Government of Northwest Territories to develop an On-Reserve First Nations guidance document and planning template for communities wanting to develop their own water protection plans.

The water protection planning template has five parts, each involving community participation including: assessing water sources, identifying associated risks, taking management actions, implementing actions, and initiating annual plan reviews.

The first pilot plan was developed in Alberta with Siksika Nation, located in Treaty 7. In Saskatchewan, Muskowekwan First Nation, located in Treaty 4, was the first to develop a similar source water protection plan facilitated by Department of Geography and Planning graduate student Kellie Grant, with Patrick as supervisor.

For Muskowekwan Water Treatment Plant operator Julius Manitopyes, the water source protection plan helped bring reassurance to the community that their water is safe to use.

“In our community, we have babies, we have Elders—our membership— (the plan) reassures them that the water is good, the water is safe now,” he said.

Manitopyes is also part of Muksowekwan First Nation’s water project management team.

The implementation of the water source protection plan led to the development of the new Muskowekwan water treatment plant in 2020. The new water treatment plant offers to clean and refill water jugs, saving community members money and time travelling to urban centres to buy clean water.

The water treatment plant also provides the opportunity to continue planning for new water and sewage lines to new subdivisions of the community.

“A lot of these ideas came out of the source water protection plan,” Manitopyes said.

More than a dozen Saskatchewan First Nation source water protection plans have been developed since then—including in Okanese First Nation, and Onion Lake Cree Nation—all facilitated by Patrick’s students and watershed partners.

“First Nations in Saskatchewan have become leaders in drinking water protection planning in Canada,” Patrick said.

2. Potential risks to water sources vary from community to community

From cracked water cisterns to unregulated landfills, risks to local water sources can vary across regions in the country, Patrick said.

In Muskowekwan First Nation, the water source protection plan led to cleaning of household water cistern systems. The plan also identified risks and encouraged changes to managing old oil, gas, and anti-freeze liquids. This led to the community moving in the direction of recycling those materials.

“(The plan) has a lot of great spinoffs that are good, beneficial to our First Nation and to our people,” Manitopyes said.

In Saskatchewan, there are a large number of old farms and houses with their own wells. Many private wells were abandoned when households switched to municipal water systems, while in some First Nations communities, many private wells were abandoned when households switched to on-reserve trucked water delivery.

Old wells can become an open conduit to groundwaters, Patrick explained, with abandoned wells and unregulated landfills posing more risk to groundwater sources in Saskatchewan.

“It’s important to pull out those old well casings and decommission the abandoned wells,” he said.

“Mapping potential threat to source water is helpful to understand exposure to risk, and to remove or reduce those risks, through a community planning process. In the end, it takes much more work, and cost, to remediate a contaminated water source than to proactively protect a water source,” Patrick said.

Unregulated landfills and automobile disposal sites can all pose risks to groundwater sources with chemicals, oils and liquids seeping into the ground.

Manitopyes noted that one of the ways the water protection plan was introduced to the community was through presentations to students at Muskowekwan School. Students helped introduce ideas presented in the plan to their households.

“The kids will tell them (adults) how important it is to keep our water safe, how important it is, what we’re doing in that area. People listen to their children—I know that for a fact, I’m a grandpa—I listen to my grandchildren.”

Patrick noted that First Nations communities in Saskatchewan—such as Muskowekwan First Nation—are training their own water treatment plant operators, improving on-reserve water infrastructure, experimenting with advanced treatment technologies, and developing their own drinking water safety guidelines and regulations.

“The biggest importance (of the water protection plan) I believe, is having membership reassured that we’re doing what we can to make sure that the water is safe for them, for their children,” Manitopyes said. “Right now, we get people coming to our First Nation for water, from all the communities (around Muskowekwan).”

Together, we will undertake the research the world needs. We invite you to join by supporting critical research at USask.