Lost concerto by German music master and Mozart editor resurrected in Saskatoon

A treasure trove of musical scores written by a pivotal figure in 20th century German music has been resurrected from a Saskatoon basement.

Music written by Heinz Moehn (1902-1992), a German composer and leading editor of musical scores by Mozart and other towering figures in classical music, had been believed lost.

Saskatoon musicians were astonished to discover the German composer’s papers were right here in the city—stored by his grandson in a plastic bag in his basement, alongside his vinyl record collection.

For 30 years, Johannes Dyring, grandson of the German musician and editor, preserved Moehn’s archive hoping that one day his grandfather’s concerto, chamber music and choral works would again be performed.

But it was in Saskatoon—where Dyring moved to in 2015 from Sweden to take up a post at the University of Saskatchewan (USask)—that the right synergy existed between musicians and music scholars to resurrect his grandfather’s work.

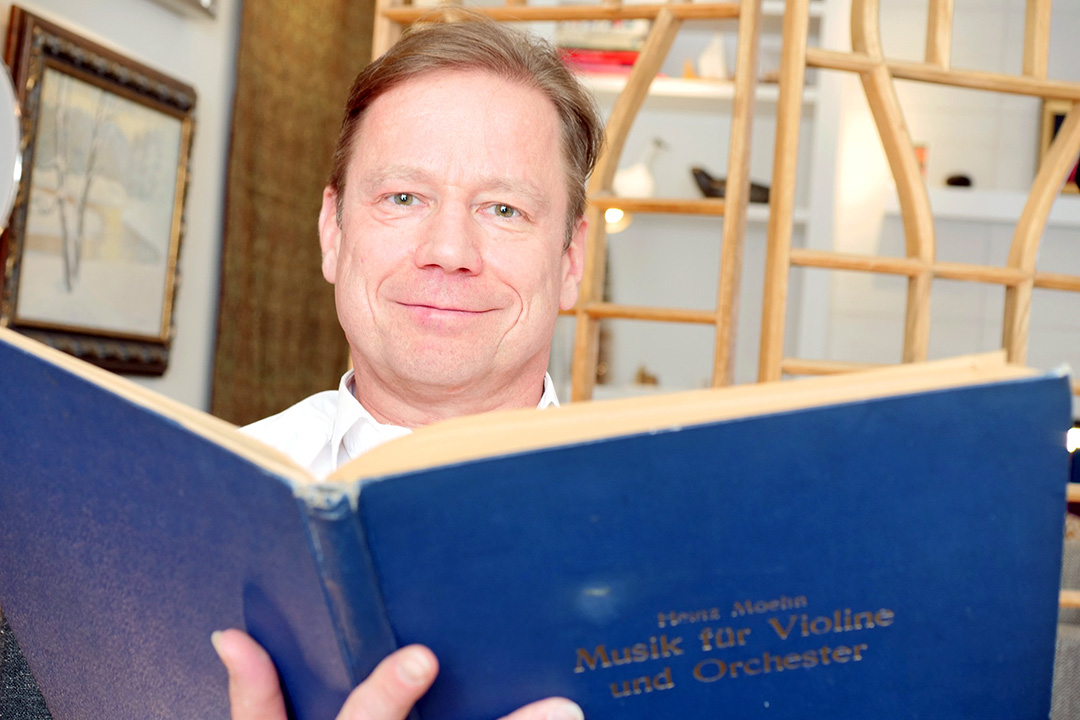

The re-emergence of the lost manuscripts has inspired the North American premiere of a beautiful Moehn concerto entitled Music for Violin and Orchestra, last performed 80 years ago in Germany.

It was a chance conversation at a business lunch between Dyring, managing director of USask Innovation Enterprise, and a Saskatoon musician that set in train the events which will culminate in the Canadian premiere by the Saskatoon Symphony Orchestra (SSO) on March 23rd.

The catalyst was Dean McNeill, USask professor of brass and jazz who plays the trumpet in the orchestra. He was fascinated to learn that Dyring had not only brought Moehn’s scores to Canada, but was keen for them to be performed here.

McNeill introduced the composer’s grandson to Eric Paetkau, conductor and music director, and Mark Turner, SSO executive director and handed him a copy of the music, suggesting it could be an exciting artistic venture.

“I thought from the beginning this is great,” said McNeill. “It would be great if our own symphony could play this. There is a really compelling story behind it: the score had been sitting in a closet since 1938 and it deserves to see the light of day.”

Paetkau knew of Moehn’s work as a major music editor, and was intrigued to learn his manuscripts were in Saskatoon.

“When they said Heinz Moehn, I thought ‘I know this name,” said Paetkau. “For years I had seen edited by Heinz Moehn’ on musical scores. His name is on a lot of musical scores on my shelves. It’s not just the rediscovery of Moehn’s work but his connection with Saskatoon—and the fact his grandson is here—that makes this so interesting.”

At the Finding Heinz Moehn evening concert, Moehn’s edition of Mozart’s Requiem will be performed by the SSO and USask’s Greystone Singers. As well, Moehn’s own concerto, edited by USask music lecturer and composer Paul Suchan, will be performed.

“It is beautiful music—very melodious and uniquely modern,” said Suchan. “He represents a sound you wouldn’t hear in other composers. There are elements that were very traditional but he was clearly influenced by modern music. He uses the kind of chords you would hear in jazz.”

The initiative has also led to a USask research project, further enhancing the formal partnership between USask and the SSO.

Moehn was a leading editor of composers’ original scores for the major musical publishing houses Barenreiter, and Schott, and was one of the editors of the definitive complete works of Mozart, which is still used by concert halls around the world. He also edited scores by Handel and contemporary German composers including Ernst Krenek.

His archive of papers—which Dyring describes, with a wry smile, as a pile of yellowing and tatty manuscripts—is now being combed through by Canadian musicians and music scholars. Alongside dozens of Moehn’s compositions, there are letters from leading composers in pre- and post-war Germany.

Amanda Lalonde, an assistant professor in the USask music department who leads the research, says Moehn is not only interesting as a composer in his own right, but because of his links to some of the most important 20th century figures in European music.

Lalonde has recently been awarded $25,000 from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) to research Moehn’s work, and edit his scores, in a collaboration between the music department and the SSO. The one-year joint project, involving students, will include a mini-documentary, recorded interviews with performers, a multi-media website, and live and recorded performances of a selection of Moehn’s musical works.

“This project is important, not only because we will learn more about Moehn's multifaceted career, but because it might add another layer to our understanding of the impact of German cultural policy on music before and during the Second World War,” said Lalonde.

From the 1920s, Moehn wrote over 40 of his own original musical works including solo vocal compositions, choral works and chamber compositions. They included a song dating from 1946—perhaps reflecting post-war German austerity—entitled On the Black Market.

Moehn’s multi-faceted musical career was affected by the cultural policies of the Third Reich, and his work as a composer slowed down during the war years.

He was choral and operatta director of the Mainz Stadttheater during the Second World War and was initiator and director of the Wiesbaden Orchesterverein from 1952 to 1959. Yet the musical styles of composers he admired and with whom he was associated were denounced by the Nazis for being Jewish, or too modern and ‘degenerate.’

His collection of papers includes letters from Hans Werner Henze and Ernst Krenek, two modernist German composers whose work he edited.

Henze, who was conscripted into the German army during the Second World War, was left wing and gay, and after the war, published works influenced by jazz and Arab music. He embraced atonality in his work—which was condemned as modernist during the Third Reich—and later worked in Cuba.

Krenek was an acclaimed composer before Hitler’s rise to power and wrote a jazz opera in 1926 whose main character was a black jazz musician. Jonny spielt auf was a sensational hit throughout Europe.

But Krenek was condemned and persecuted by the Nazi regime. The poster from his jazz opera was the centrepiece of the Nazis’ 1938 Degenerate Music exhibition, which aimed to whip up condemnation of music deemed un-German, including compositions by Jewish composers. Krenek fled to America in 1938, and in the 1950s moved to Toronto where he taught at the The Royal Conservatory of Music .

Also preserved are letters from Wilhelm Rettich, a German-Jewish composer and conductor who fled Nazi Germany and survived the war in hiding in the Netherlands.

Moehn also corresponded with Franz Schrecker, an acclaimed Austrian composer whose father was Jewish. Before the Nazi period, he was one of the pre-eminent figures in German opera. However, the Nazis marginalised Rettich because of his Jewish background, and his works and performances were disrupted by right-wing demonstrations or cancelled. He died a marginalized figure in 1934.

Some of Moehn’s own works—including his concerto Music for Violin and Orchestra—demonstrate his own modernist leanings. The title of the concerto is a homage to Rudi Stephan, an acclaimed young German modernist composer whose stellar career was tragically cut short when he was killed in the First World War. Moehn so admired Stephan that he named his own orchestral work after a work by Stephan and named his son (Johannes’ father), Rudi Stephan after him. Coincidentally, SSO Executive Director Mark Turner also happens to be a great admirer of Rudi Stephan’s work.

Moehn was also an authority on reducing orchestral scores into works for piano, including Mozart operas. His piano ‘versions’ of major works have been performed in their own right and are still used internationally by singers, including opera singers rehearsing with piano accompaniment.

Dyring, who himself has played cello, violin and Flamenco guitar, spent most of his childhood in Germany and recalls visiting his grandfather in Wiesbaden. He spent hours discussing classical music with him and listening to him play his compositions on his upright piano. He remembers him as a “perfectionist” with a perfect ear for music who would not be disturbed while he was working, only relaxing at 5 pm with a cigar. Dyring’s father once interrupted him when he was composing and found an ink pot flying past his head.

Dyring, who holds a PhD in nuclear particle physics and was founder and CEO of a number of high-tech companies in Sweden before moving to Saskatoon.

“It was astonishing to find so many people in Saskatoon who had a connection to the work of my grandfather and wanted to see his music performed again,” said Dyring.

“What are the odds, It’s incredible that all these jigsaw pieces have come together in Saskatoon, which in a way speaks for the Canadian and Saskatchewan culture and mindset—and that so many people knew about my grandfather’s work,” said Dyring.

“For the last 30 years I tried in Germany and Sweden to find an orchestra to play the music. Here, the people from the symphony straight away knew about my grandfather and his significance.”

-30-

To learn more, watch here.

For more information, contact:

Jennifer Thoma

Media Relations Specialist

University of Saskatchewan

306-966-1851

jennifer.thoma@usask.ca