USask computer-based simulator tests insects for effects of new pesticide

SASKATOON—University of Saskatchewan (USask) researchers have used a novel combination of techniques to compare the effects of two families of pesticides used in agriculture, and found that at low dosages the newer pesticide is less toxic than a currently used neonicotinoid one.

By USask Research Profile and ImpactUSask biology professor Jack Gray’s research on locusts, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), may have implications for understanding the link between these pesticides and mortality in other species such as the “colony collapse disorder” responsible for the deaths of millions of bees worldwide.

“There is controversy over neonicotinoid pesticides,” said Gray. “Their development suggested they were safer than other pesticides, but it is more complicated because their effects at non-lethal doses on insects and other species needed to be investigated further.”

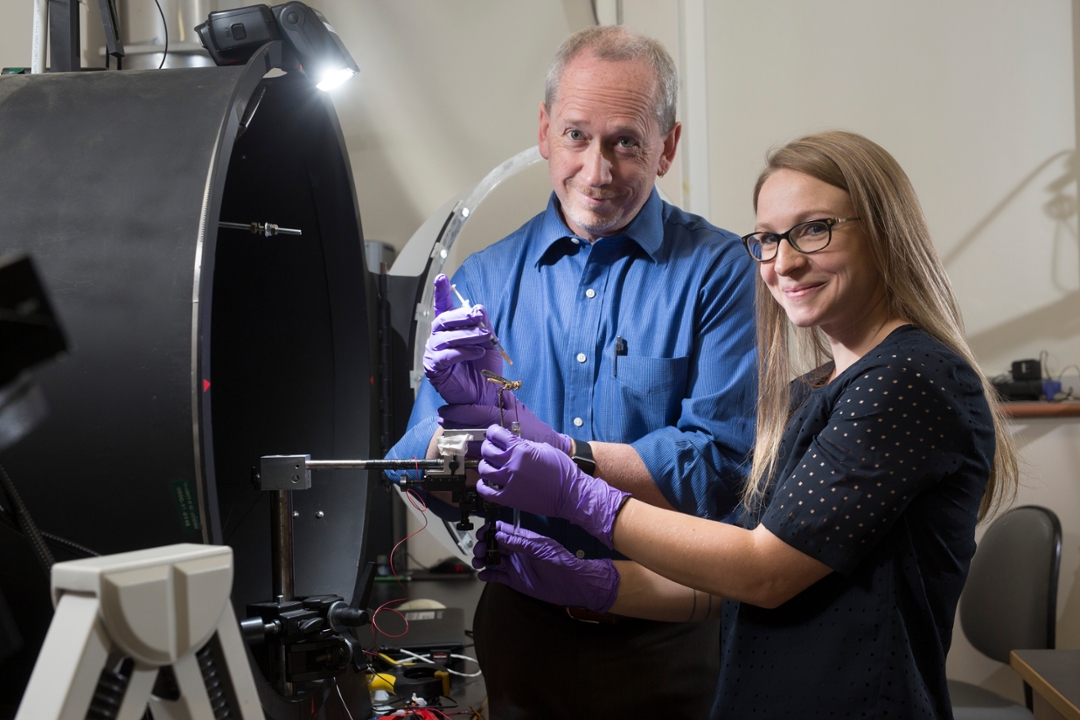

From his previous studies with locusts, Gray designed a virtual flight simulator in which he tested how non-lethal doses of pesticides can affect the insects’ ability to visually detect moving objects such as trees and predators. He and his team found that the newer sulfoxamine pesticide, sulfoxaflor (SFX), does not impair the insects’ motion detection ability, while the current neonicotinoid imidacloprid (IMD) does.

“Even though this suggests that SFX isn’t as toxic as the other pesticide at low dosages, more testing is needed to establish whether it a safer, preferable option for agriculture use,” said Gray.

Gray and his team used an approach that looks at behaviour and neurophysiology, which have seldom been applied together for studying pesticide effects. The results confirmed that IMD had negative effects on the locusts’ ability to jump and escape dangers, while SFX did not. A potential explanation may be that SFX does not bind as strongly to the same receptor that determines the insects’ sensitivity to the pesticides.

The USask team chose locusts because their nervous system is well-studied, and the neurons that regulate their motion detection are common to a variety of other species including birds, and likely even humans.

“These findings may be applicable to other species to understand how these pesticides affect how fast the nervous system can send information,” said Gray.

By using small electrodes in the insect’s thorax, former USask PhD student Rachel Parkinson—first author of the paper—measured the electrical signals directly from a neuron in the insect’s nervous system that detects visual motion and controls flight.

“The reaction time of locusts treated with the IMD pesticide slows down, impairing their ability to avoid objects,” said Parkinson, now post-doctoral fellow at the University of Oxford.

The USask team also includes PhD student Sinan Zhang. The research is funded by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC), the Canada Foundation for Innovation, and USask.

-30-

For more information, contact:

Victoria Dinh

Communications and Media Relations Co-ordinator

University of Saskatchewan

306-966-5487

victoria.dinh@usask.ca