USask researchers’ study of Salmonella transmission first of its kind

SASKATOON – University of Saskatchewan (USask) scientists are pursuing research unlike anything else in the world to learn more about how one of most infamous food-borne illnesses spreads.

By Matt Olson for Research Profile and ImpactDr. Aaron White (PhD) and his team recently received a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant of $160,000 over five years to get to the heart — or the gut — of how and why Salmonella bacteria continue to thrive.

“For some of these types of pathogens, it’s difficult to study how they survive so long in the environment,” White said.

As he explains it, Salmonella is one of the most common food-borne pathogens in North America, and it is notorious for causing painful problems in the stomach and intestine.

Before Salmonella bacteria can be purged from the body, White said the population splits into two forms: extremely infectious and virulent single-celled Salmonella, and cells that clump together to form what is called a “biofilm” — a cluster of cells that stick to each other and form a membrane around them.

Biofilm cells can survive for a long time in the environment — for example, after the bacteria are expelled from the human body — but are not nearly as transmissible as their single-celled counterparts.

White’s research at USask’s Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization (VIDO) focuses on how Salmonella changes forms.

“By understanding this splitting, we begin to understand how Salmonella survives better in the environment and perhaps how to stop it,” he said. “We start to understand our immune response to Salmonella, and the long-term impacts of Salmonella infection.”

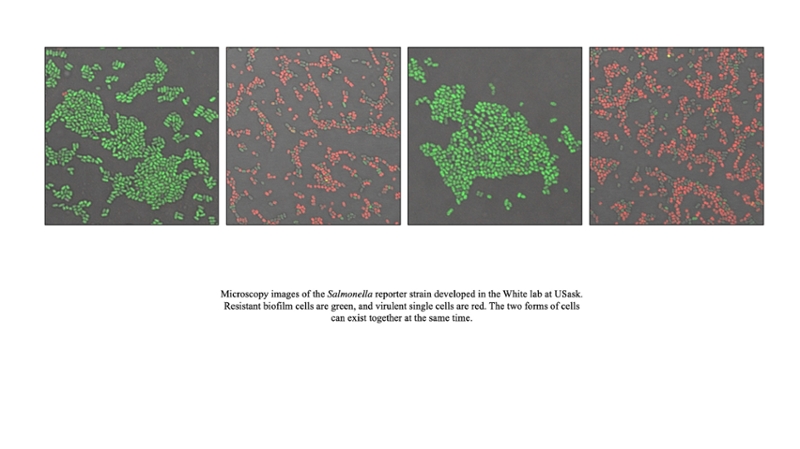

The team’s research program is already underway, using mice. White lauded master’s student Michelle Gerber for creating a “reporter strain” of Salmonella that turns green when it transforms into a biofilm cell, and red when it remains in its single-celled, virulent form.

The reporter strain is one of the ways they’re able to closely monitor the change in Salmonella bacteria, and pursue research that White said is unlike anything else in the world.

“It’s quite exciting,” he said. “It’s great for trainees. We have a chance to redefine how we approach this bacterium, make better vaccines and control infections, by studying these new ideas.”

While they are on the cutting edge of research already, White is looking ahead to what might come next. He said through their NSERC-funded research they have already identified a connection between the proteins present at the formation of biofilm cells and those that exist in human neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s.

“It’s still in the early stages, but that might be the most exciting thing to come out of my research,” he said. “It’s a big subject to tackle.”

As the team learns more about what causes Salmonella to split and survive, White is excited about the questions his program might answer about the troublesome bacteria — and other questions this research could answer in the future.

-30-

For media inquiries, contact:

Brooke KleiboerUSask Media Relations

306-966-1388

brooke.kleiboer@usask.ca