JSGS MPA graduate has life-changing experience on his first day of classes

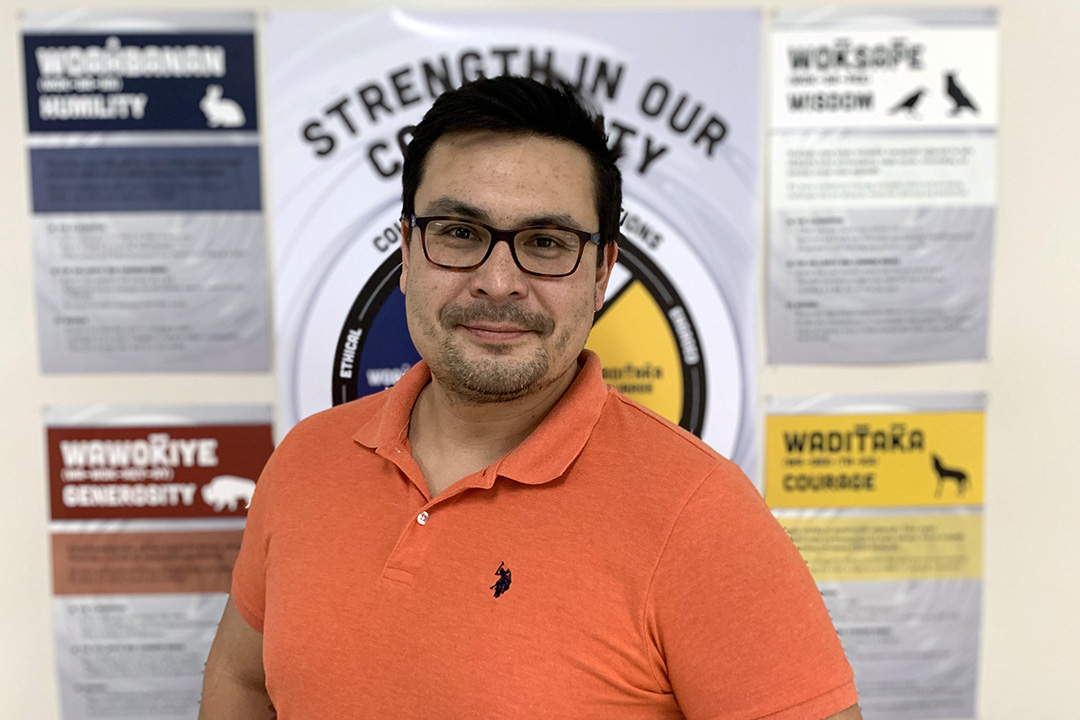

Ian Worme graduated with a Master of Public Administration (MPA) degree after a five-year academic journey that began in the most unconventional way—with the birth of his youngest daughter.

By Emilie NeudorfJust eight hours after welcoming his daughter, Julie, into the world, Worme shifted his focus from the birthing room at Royal University Hospital (RUH) to the MPA classroom in the Johnson Shoyama Graduate School of Public Policy (JSGS) at the University of Saskatchewan (USask). Luckily, for him, RUH was only a quick walk away from where he would spend the next five years as a part-time graduate student.

“I went to class that day with roughly four hours of sleep,” said Worme. “It was a surreal moment in time!”

Worme would go on to spend the next three nights at RUH with his family, stepping out for portions of each day to attend classes. The melding of these two events made for a memorable start for both him and his family.

Five years after celebrating the birth of his daughter, Worme is now celebrating the completion of his MPA degree, officially received on June 1, 2021, during USask’s virtual convocation week.

Worme is from Kawacatoose First Nation in Treaty 4 territory on his paternal side, and Chisasibi Cree Nation near James Bay in Quebec, on his maternal side. He is also an educator, consultant, and proud community member of Whitecap Dakota First Nation, the reserve where his partner is a registered band member. He values self-knowledge and his Indigenous identity which come from his language, culture, and great respect for the outdoors—a place where you can often find him with his two daughters.

Interested in administration, government, partnerships, and politics, Worme was drawn to JSGS after completing his Bachelor of Education degree through the Indigenous Teacher Education Program at USask. He saw many ways in which an MPA could benefit the work he was doing.

“During my studies, I was able to apply new knowledge and concepts to my actual work in the field of education, governance, and partnership development,” said Worme. “Plus, studying as a part-time student meant that I had the flexibility needed to continue working full-time while spending time with my growing family.”

Throughout his time at JSGS, he also participated in study groups, potlucks, and attended the many guest lectures organized by the school. These activities were important in building relationships and learning from fellow students. He found that listening to the perspectives and stories of international students was valuable—especially those of Indigenous students from Northern Russia.

Looking to the future, Worme would like to do work focused on treaty education and governance. Ideally, he would like to instruct and/or develop compulsory courses that address the gaps he sees in treaty education and Indigenous-focused policy.

“I want to see the mandate of treaty education be truly fulfilled and valued within the non-Indigenous public sector, in both education and government,” said Worme. “Treaty education needs to be an actual course facilitated in each school with a designated provincial curriculum, and we need to see universities with compulsory treaty education. More is needed to educate citizens on the impacts of race-based policies and legislation.”

He also wants to see land-based education taught in all First Nation communities, where it is part of the curriculum set by the community. Worme’s advice for new students at JSGS is to take as many Indigenous-focused courses as they can so that future generations may live in a Canada with well-informed policymakers, leaders in government, and educators.

“I believe that treaties are constitutional documents that aided in the mapping of the past and present privileges Canadians receive today and that we, as a society, have shared social capital in this country,” said Worme. “It is vital as policy students that we all understand how governmental actions have impacted the livelihood of Indigenous Peoples in Canada.”