USask shoulder motion study nets NSERC support

The same tools used for creating special effects in film and video games are being harnessed by a University of Saskatchewan (USask) researcher determined to better understand shoulder function.

By Jeanette NeufeldDr. Angelica Lang (PhD) was recently awarded a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) for her research, which uses a system of motion capture cameras to measure and analyze shoulder motion.

Lang said these types of camera systems are revolutionizing the field of biomechanics.

“It’s allowed us to measure the body in ways you couldn’t even 30 years ago,” she said.

Lang is an assistant professor and director of the Musculoskeletal Health and Ergonomics Lab based at the Canadian Centre for Rural and Agricultural Health in the USask College of Medicine. She hopes to develop a standardized procedure to measure movements of the scapula – commonly known as the shoulder blade – eventually leading researchers to greater understanding of what causes shoulder pain and how to remedy it.

The $165,000, five-year grant will allow her to advance her investigation of the most repeatable and reliable methods for scapular motion tracking and analysis. As an early-career researcher, she also received a Discovery Launch Supplement of $12,500.

“The scapula is so difficult to measure and track,” she said, reaching for the small model of a scapula displayed prominently in her office, to illustrate the unique movement patterns of the triangular bone.

Her focus on the shoulder began during her PhD work at USask, when she evaluated upper limb function in breast cancer survivors. She also completed a review, finding that out of 246 studies that measured shoulder function, only seven used biomechanical measures.

“It really showed a gap,” she said.

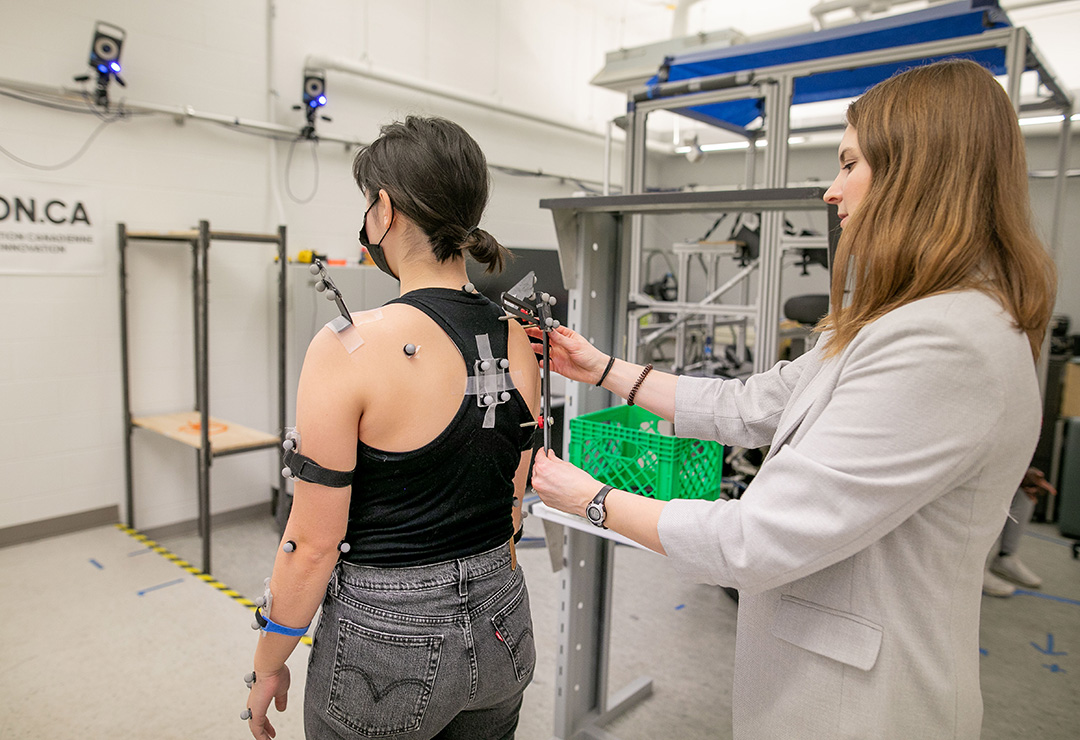

Now a faculty member, this finding inspired her to further her work, with the assistance of several graduate student and medical student researchers. In the lab, Lang and her assistants attach reflective markers to the upper body. Their standard approach is to use a double calibration method, meaning they locate the landmark areas of the scapula in two different arm positions to account for how the reflective markers move with the skin.

Lang plans to refine this method using different arm positions or different calibration tools. She hopes that by testing these methods they can determine which approach most reliably tracks scapular movement.

She then runs volunteers through a standardized test protocol of eight different movements that she has developed.

“What I think is novel is that I’m trying to apply this to functional movements,” she said.

As Lang explains, most existing research focuses on raising the arm up and down. Her work builds on this, reflecting how the shoulder blade really moves when someone is completing day-to-day tasks. Lang demonstrates the standardized movement patterns, such as combing ones’ hair or tying the strings of an apron.

She then plans to use an open-source computer program to analyze the data, which she hopes will further improve the accessibility of her research. Lang hopes that by creating a system that’s easy to use and replicate that more researchers will be able to incorporate scapular measurements when evaluating upper limb function.

“If we can create and share an easy-to-use protocol, then hopefully more people will include the scapula when they’re doing research, and I think that will give us richer information about what’s happening in the shoulder,” she said.

Together, we will undertake the research the world needs. We invite you to join by supporting critical research at USask.