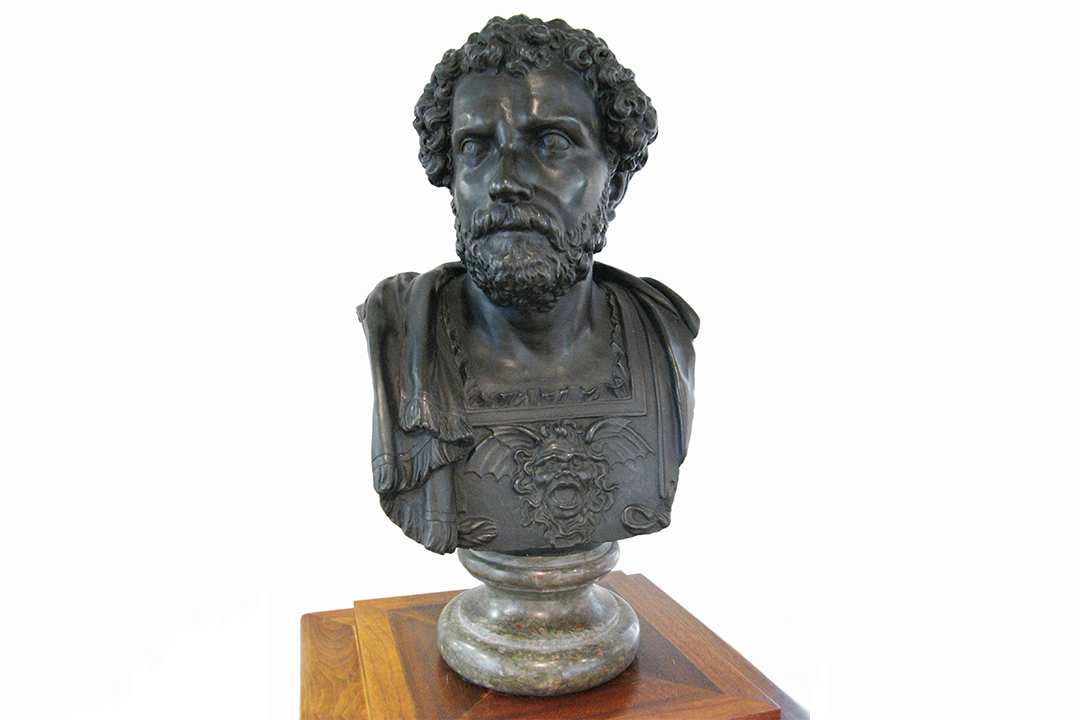

Uniquely USask: Napoleon’s bust of Hannibal a USask treasure

During his rule as Emperor of the French, Napoleon Bonaparte spent long days and nights working in his study at the Château de Saint-Cloud near Paris. On the mantlepiece above his favourite chair sat a bronze bust of one of his idols, the Carthaginian general Hannibal.

By Chris PutnamA bust of Hannibal in the collection of the Museum of Antiquities at the University of Saskatchewan (USask) is the very same sculpture, believes Dr. Tracene Harvey (PhD).

“It’s not every day you have such a strong connection to Napoleon here in Saskatchewan,” said Harvey, director of the museum in the College of Arts and Science.

The bust was priceless even before its link to Napoleon was found. The Museum of Antiquities’ former curator, Catherine Gunderson, discovered in the late 1980s that it came from the studio of François Girardon—a sculptor for King Louis XIV of France who played a major role in the decoration of the Palace of Versailles.

The bust was created either by Girardon himself or by his student Sébastien Slodtz, said Harvey.

Gunderson’s research also led her to suspect the bust was once owned by Napoleon. In 2014, Harvey asked Helanna Gessner, a student assistant at the Museum of Antiquities, to investigate further. That summer, Gessner found a description of the emperor’s bust of Hannibal in the memoirs of Napoleon’s private secretary.

“I immediately rushed to tell Tracene and everyone else in the office, ‘Look, we found it!’ I was pretty ecstatic,” said Gessner, who now works at the Diefenbaker Canada Centre.

Only one other bust matching the description is known to exist, and its whereabouts during Napoleon’s time are accounted for. That makes the Museum of Antiquities’ bust “a very strong candidate for Napoleon’s,” said Harvey.

There are still questions about how the bust made it from France to USask.

“We’re still trying to find the exact path that it took to get here. Parts of that journey we may never know,” Harvey said.

After Napoleon’s fall from power, the bust may have come into the possession of the Louvre Museum in Paris. It later travelled to New York, where a collector purchased it at an auction in 1939 for just $69. Judge John C. Currelly acquired it and donated it to USask’s Museum of Antiquities in 1988.

Other mysteries remain. The memoirs that describe the bust also mention a sculpture of Hannibal’s Roman adversary, Scipio Africanus, which sat next to it on Napoleon’s mantlepiece. The second bust has been lost to history.

“Wouldn’t that be a treat to find that Scipio bust someday?” said Harvey.