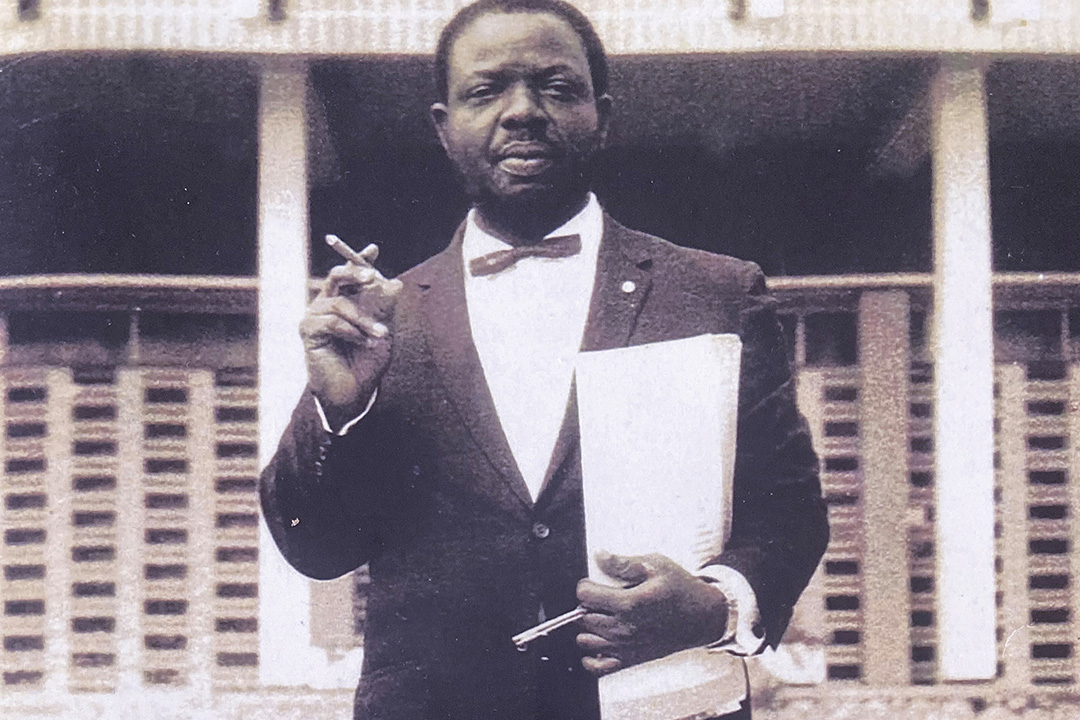

Black History Month: The life and times of one of USask's first Black students

He would go on to have a celebrated career as a doctor spanning five decades of service on two continents.

By James ShewagaHowever, Dr. Theodoric (Ted) Nwafor Chukwulobe Agulefo (MD, DPH) had no idea what was in store for him, and what triumphs and tragedies awaited, when he boarded a passenger ship as a teenager from Nigeria and headed to the United States.

“We are extremely proud of him,” said his eldest son Emeka Agulefo, who practices law in Toronto. “I can’t even walk in his shoes; I can’t even fit half of his shoes. He helped so many people.”

Dr. Agulefo was born in the Nigerian village of Ogidi on Nov. 1, 1926, and would go on to have a remarkable life and career, filled with historic moments in Africa and North America.

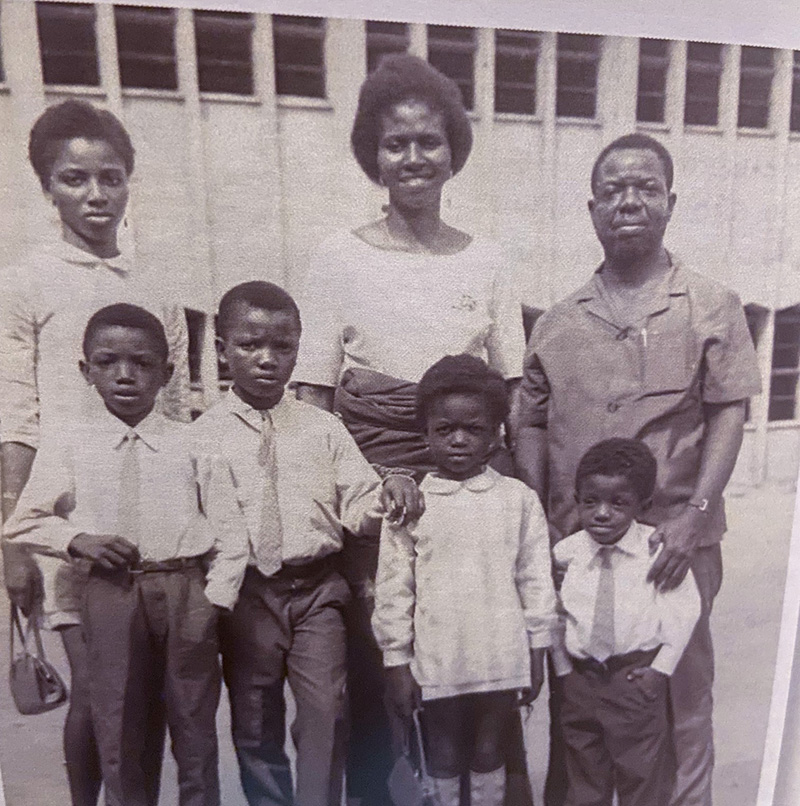

He served as a physician and senior public health official in both Canada and Nigeria, served in an elite unit in the Canadian military making dangerous experimental parachute jumps, survived the Nigerian civil war, death threats and two coup d'états, and went on to raise a family of four children in Canada with his wife of 53 years.

When he was in his early 20s, Agulefo also made history when he became one of the very first Black students at the University of Saskatchewan (USask), breaking new ground as the only member of the Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC) community in USask’s medicine class of 1954.

“He always said he enjoyed his stay there in Saskatoon,” said his son, noting that his father was dating the mayor’s daughter at the time. “The family accepted him so well, and he definitely enjoyed the University of Saskatchewan. Where he faced racial prejudice was in the U.S., and that’s why he crossed over to Canada.”

In 1948 when he was only 18, Agulefo and his cousin headed overseas to attend college in the U.S. on scholarship. His son recalls the story his father relayed to him that after arriving in South Carolina after a six-week voyage, his father was detained by immigration officials, who believed he was a stowaway and arrested him. The Nigerian liaison office appealed to the Governor of New York on their behalf and he was released from custody.

“He sent two first-class tickets for them to get on the train, so they let them out of jail after the governor of South Carolina interceded and said ‘These boys are going up north to Yankee territory’,” Emeka recalled.

However, despite holding first-class tickets, they were not allowed into the first class section of the train until they crossed the Mason-Dixon Line, the demarcation line that informally separated the northern states from the southern states during the Civil War.

“My father had never experienced this type of racism, so he was very upset and said if they could have found a ship to take them back to Nigeria they would have hopped on it, because they were thinking about what they were going to face when they got to the university.”

Agulefo struggled through more incidents during his year of college studies in Ohio, including a racist professor who refused to give him the grade that he had earned, and a white tennis opponent who refused to face him on the court in the state championships. Disheartened by what he had experienced, Agulefo headed north to Canada to complete his education, with the assistance of the Nigerian liaison office. He first earned a Bachelor of Arts at Queen’s University before heading west to earn a science degree and medical certificate in 1954 at USask, where he had fond memories for the school and for its most famous alumnus, Prime Minister John Diefenbaker.

“His favourite Prime Minister in Canada was Diefenbaker, and he always spoke very well of Diefenbaker,” said Emeka.

From the Prairies to the Maritimes, Agulefo moved on to Dalhousie University in Halifax to complete medical school in 1957. It was while at Dalhousie that Agulefo also joined the Canadian Armed Forces, training with the Princess Patricia Battalion paratroopers—Canada’s first peacetime paratroop battalion—during the summers to pay for his classes in fall and winter.

“He would do a lot of parachute jumping, since they paid very well to volunteer to test these new experimental parachutes and he messed up his back from all those jumps that he did,” said Emeka. “Luckily he didn’t break his back, but he was well respected and rose to the rank of major.”

Records show that Agulefo was first certified in 1957 by the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario to practice medicine in Canada, marking the start of a remarkable 47-year career as a physician in Canada, the U.S., and Nigeria.

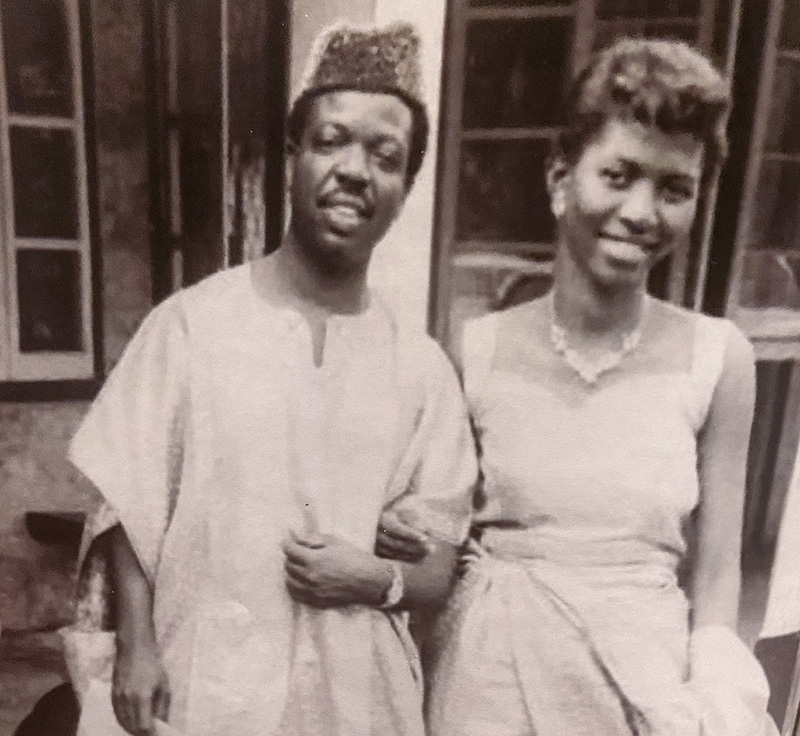

After a year working as a physician and surgeon for the Abitibi lumber company in Thunder Bay, Ont., Agulefo returned home to Nigeria, married his wife Alice in 1960 and set up a successful private practice while also establishing the Trinity Yankee Hospital in Port Harcourt in the southern region of Biafra. Agulefo also served as physician and surgeon for Nigerian Railways, Ports Authority and international companies like Halliburton in the oil-rich region.

However, he would soon become entangled in the Nigerian Civil War, as a member of the self-proclaimed Republic of Biafra that attempted to secede from the rest of the country in a three-year conflict that is estimated to have cost up to three million lives, most from starvation and disease. With an abundance of oil among the resources at play and world powers scrambling for influence on the continent, the civil war featured unlikely allies like the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union supporting the Nigerian government, with France and Israel among those supporting Biafra.

While treating wounded soldiers throughout the war, Agulefo also became the leader of the Port Harcourt Civil Defence Brigade and was one of 10 members appointed to the Biafran Constitutional Assembly. When Biafra surrendered on Jan. 13, 1970, Agulefo was forced to flee the country, along with the other leaders of the breakaway state.

“The reason why my dad left was he was on a list of people to be executed after the war, because my dad was Biafran and was one of those who signed the Declaration of Biafra,” said Emeka, who was five years old when his father fled, as the rest of the family remained in Nigeria for four months until they were reunited overseas.

“In the summer of 1972 we arrived in Canada and we stayed in Canada until 1979 and then one of my dad’s best friends became vice-president of Nigeria and my dad was granted political asylum and was offered the position of Minister of Health for one of the states in the former Biafra region,” his son recalled, noting his father was serving as the deputy chief medical officer for the City of Toronto in 1978-79 before the family returned home to Nigeria.

However, unrest continued in his home country, with military coup d'états in 1983 and in 1986, when Agulefo decided it was time to leave once again. He returned to Canada and went on to practice medicine in Toronto for 20 years before his retirement in 2005.

Dr. Agulefo was 86 years old when he passed away on June 13, 2013.

“He was a great man,” said Emeka. “He did so much, for so many.”