Revolutionizing fertility treatment

Ongoing research on ovarian follicle development at the College of Medicine is changing how we use hormonal birth control and helping patients dealing with infertility.

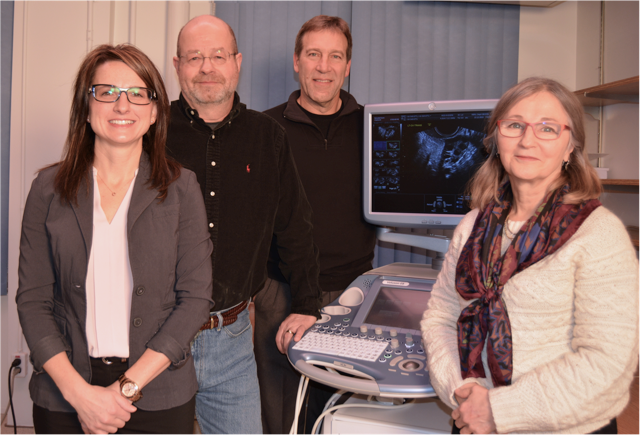

By Marg SheridanIn 2003, a team of College of Medicine researchers published work that provided a new model for ovarian function during the menstrual cycle, and now – 13 years later - they’re getting to see the clinical applications of their work come to fruition.

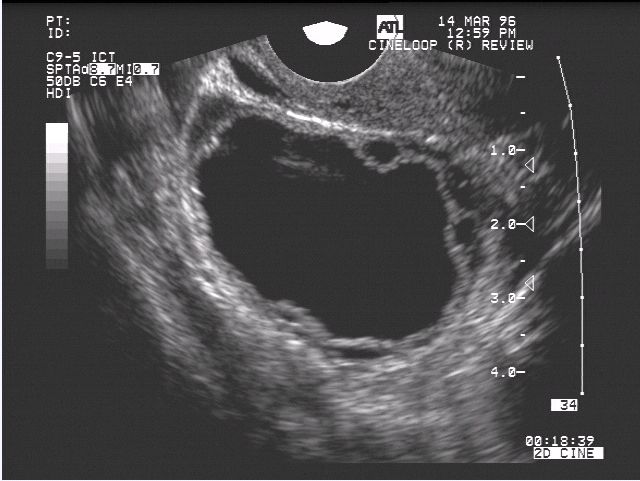

“For the past almost 60 years it was thought that follicles in the ovaries (the sacs that contain the eggs) grow at only one time of a woman’s cycle,” Dr. Angela Baerwald, an assistant professor in the Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Sciences, said of the original paper. “At that time we had published research to show that follicles actually grow at multiple times throughout a woman’s menstrual cycle but typically it only leads to ovulation during one time during the cycle.”

Collaborative research done by Dr. Roger Pierson the College of Medicine, and Dr. Gregg Adams at the Western College of Veterinary Medicine had already shown multiple waves of ovarian follicle development in animals. With that in mind, Pierson and his team (Dr. Donna Chizen and Dr. Femi Olatunbosunat) began to observe follicle growth at atypical times of the menstrual cycle in women who were undergoing fertility treatment – results that directly led to Baerwald’s research.

The research garnered quite a bit of international attention, but it was a recent presentation at the 43 International Dexeus on Women’s Health in Barcelona where the clinical applications of their research were presented.

“What we’ve been able to do now with our original work is optimize hormonal contraceptive therapy,” Baerwald continued. “We’ve shown that the majority of breakthrough follicle development in women using hormonal contraceptives (birth control pills and patches) occurs when one or more pills is missed around the time of the pill-free interval. In other words, extending the pill-free week allows enough time for a new wave of follicles to grow, and provides the greatest potential for follicles to ovulate.”

These findings have since contributed to the development of new guidelines for missed birth control pills.

“The duration of the pill-free week has been reduced or removed altogether in many oral contraceptive formulations. So instead of having seven days off from the pill each month, women may have only a four-day pill free interval.”

It has allowed for new formulations that allow the women to take the pills back-to-back for three months at a time, and then only have a period four times a year, rather than once every 29 days.

To add to that benefit is the fact that the research applies not only to the pill, but other hormonal contraceptives including patches and rings.

But contraception isn’t the only clinical application for the follicle research; it is in fact also being used to optimize infertility treatment.

“For more than 25 years, fertility therapy has been initiated at only one time of a woman’s cycle – and that’s at the very start of her cycle,” she explained. “Now that we know that follicles develop at more than one time of a woman’s menstrual cycle, some fertility clinics around the world are initiating fertility therapy at multiple set times of the cycle or randomly at any time of the cycle in women undergoing in vitro fertilization.

“The research being conducted globally (China, Italy, USA) has shown that comparable pregnancy rates and live-birth rates can be achieved when fertility therapy is initiated in conjunction with any wave versus only the first wave of a woman’s cycle. The rate of aneuploidy (abnormal chromosome numbers) in embryos from both methods was no different between groups. Thus, healthy babies are now being born with this therapy.”

This application, Baerwald stresses, has been particularly important for two groups of women seeking fertility treatment: onco-fertility patients, and ‘poor-responder’ patients.

Onco-fertility patients are those who have been diagnosed with cancer and need to undergo urgent fertility therapy prior to chemotherapy. These women need to obtain eggs and resulting embryos that can be frozen for transfer at a later date. The new results mean that women don’t have to put off cancer treatment to wait for their next cycle to start. They can instead start fertility treatment at any time during their cycle.

In comparison, ‘poor-responder’ patients are women who have undergone fertility therapy at the start of their cycle, but were unsuccessful in obtaining eggs or embryos. If not enough follicles grew during the cycle, women used to have to wait for the beginning of the next cycle to try again. However, with knowledge of follicle waves, women no longer have to wait. They can restart fertility therapy when the next follicle wave emerges.

“Preventing a delay in fertility therapy is especially beneficial for older women, as more and more women are waiting to have children," Baerwald explained. "Advanced age is the leading cause of infertility in North America because, as women get older, the number of follicles (and eggs) in their ovaries is continuously depleted."

Baerwald has expanded upon her graduate research to characterize atypical follicle development and hormone production that occurs during the perimenopause, the third clinical application of this work.

“The number of follicle waves throughout a woman’s cycle does not differ as she approaches menopause,” she continued. “However, the follicles can grow larger and produce more hormones than usual. One of the most exciting discoveries is that follicle waves can result in more than one ovulation per cycle as women age.”

These findings have potential clinical implications for understanding the increasing incidence of twin pregnancies, miscarriage and uterine cancer as women age.

When Baerwald was an undergrad student in 1997 she knew that she intended to pursue a medical degree, but it was the opportunity to work with Pierson that directed her onto a clinical research path. From there, she completed a PhD with Pierson followed by a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Ottawa. She returned to the U of S in 2005 to establish a career in women’s health research, and is currently working to complete a medical degree while balancing her research program.

It’s a lot of work, but Baerwald has already shown that, for her, it has been a very rewarding experience.

Article re-posted on .

View original article.