Study of 170-year-old thumbnail uncovers mystery of Franklin expedition

It’s long been thought that crew members of the mid-1800s Franklin expedition died from exposure to high levels of lead.

By University CommunicationsBut new research—using advanced imaging and analytical tools at the University of Saskatchewan (U of S) and two other Canadian universities to study the 170-year-old thumbnail of HMS Terror crew member John Hartnell—tells a different story.

Led by TrichAnalytics Inc. CEO and founder Jennie Christensen, the study suggests that severe zinc deficiency from malnutrition played a greater role than lead poisoning in the tragic demise of the crew during their search for the Northwest Passage.

"This is an outstanding application of cutting-edge science, at the interface between archaeology and forensics, to solve a 170-year-old mystery,” said Chris Hunt, co-editor of Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports which published the study results today. “Jennie Christensen and her team are to be congratulated on a great piece of work.”

The team used nail tissues, which provide a record of metals in the body over time, to examine metal exposure and diet throughout the early Franklin expedition.

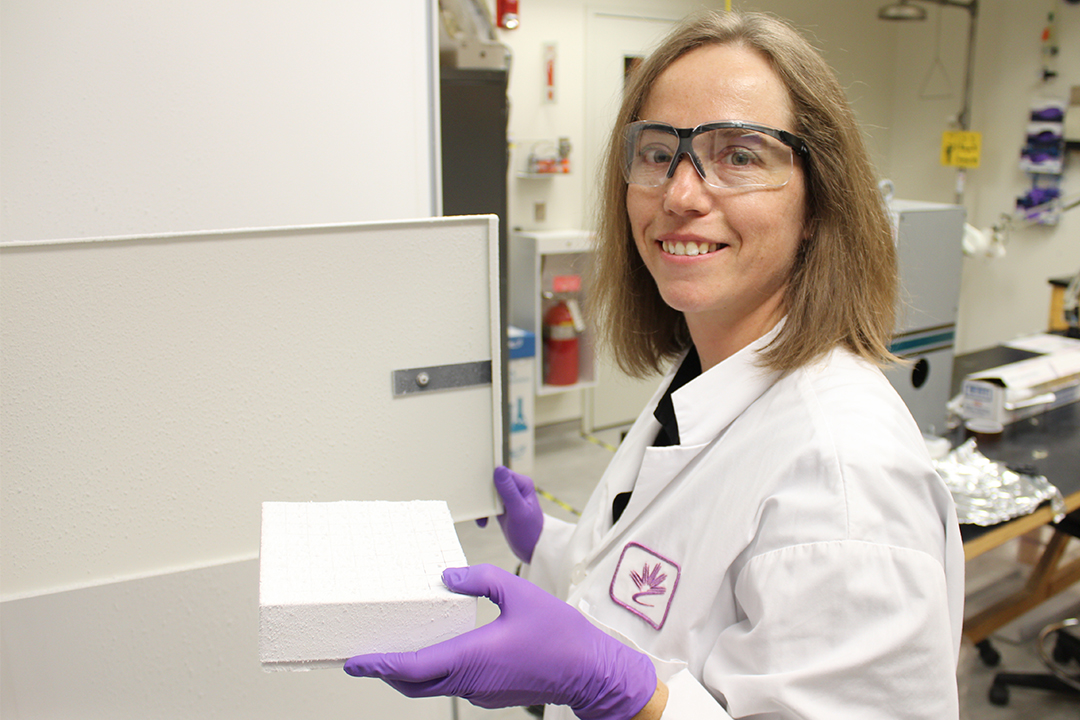

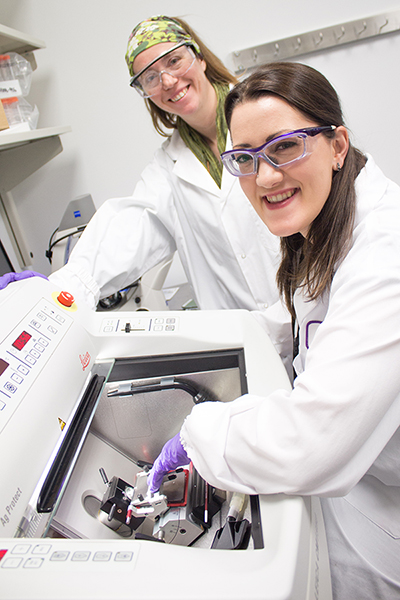

U of S scientists Joyce McBeth and Nicole Sylvain used synchrotron micro-XRF mapping at the Canadian Light Source at the U of S to assess environmental contamination in the nail samples. Christensen’s analysis of the nail samples was conducted at the University of Victoria with researcher Jody Spence using a laser ablation tool, with support from Stantec Consulting Ltd. Hing Man (Laurie) Chan used stable isotope analysis at the University of Ottawa to assess sources of protein in Hartnell’s diet.

“Our data enabled us to determine whether the metals in the thumbnail were from Hartnell’s diet or from contamination of the nail tissues from environmental sources such as coal dust on the ship,” said U of S geological sciences researcher McBeth. “This provided us with the information we needed to validate Jennie’s quantitative laser analyses.”

The study concluded that significant lead exposure did not occur during the expedition. Until his last few weeks of life, Hartnell’s lead levels were within a healthy, normal range.

Instead, the analysis found that Hartnell was severely zinc-deficient, which possibly led to immune-suppression and ultimately tuberculosis and death. Zinc plays an integral role in vitamin A metabolism, and deficiencies in zinc and vitamin A result in compromised immune function and diminished ability to fight infections, including tuberculosis. As malnourishment and zinc deficiency have behavioral symptoms similar to lead toxicity, this may explain the strange behavior of the crew members observed by Inuit peoples after the expedition had run into trouble.

“The process of starvation from tuberculosis resulted in the exponential release of previously-stored lead into Hartnell’s blood,” said Christensen. “Lead concentrations were only high and increasing at the end of his life when he was already likely near death. This explains why previous researchers discovered high lead concentrations in soft tissue, but they erroneously concluded it was due to recent exposure.”

The two ships that embarked on Franklin’s expedition, the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, were discovered in Canada’s North in 2014 and 2016, respectively. The Inuit Heritage Trust and Canadian Museum of History provided Hartnell’s thumbnail and toenail to the research group for study.

The full study is available at ScienceDirect. Read more about synchrotron micro-XRF mapping and stable isotope analysis.